Jadual Kandungan

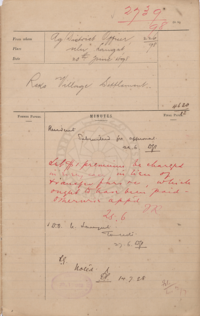

Rekoh

Dirujuk oleh

Perihal

Lokasi

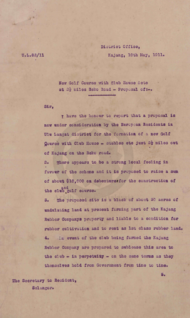

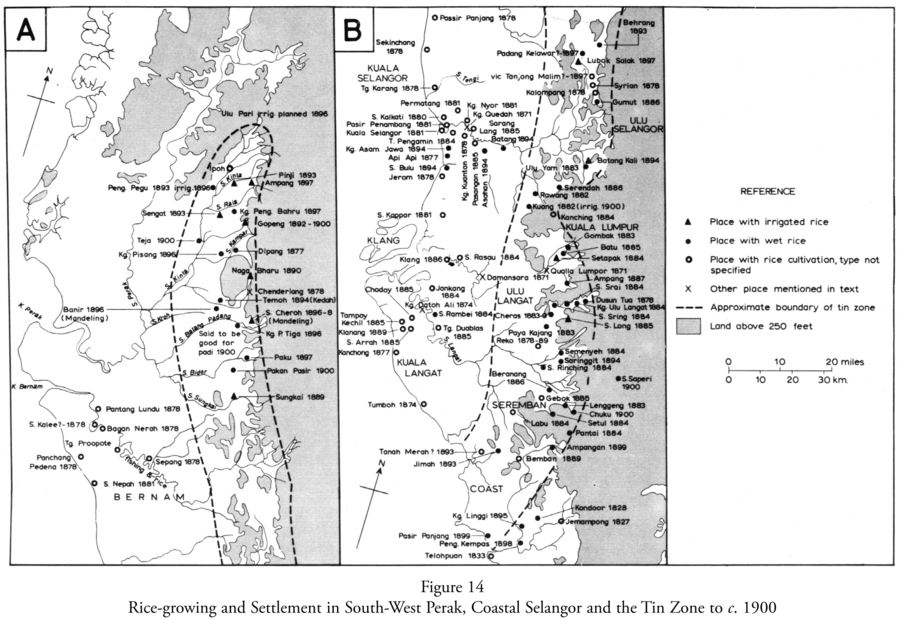

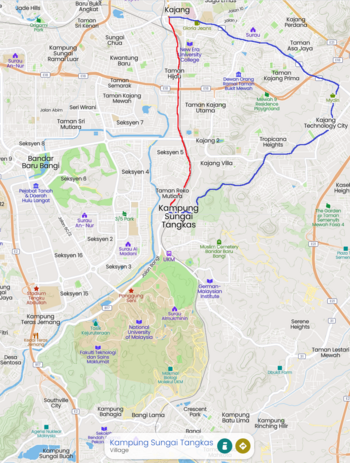

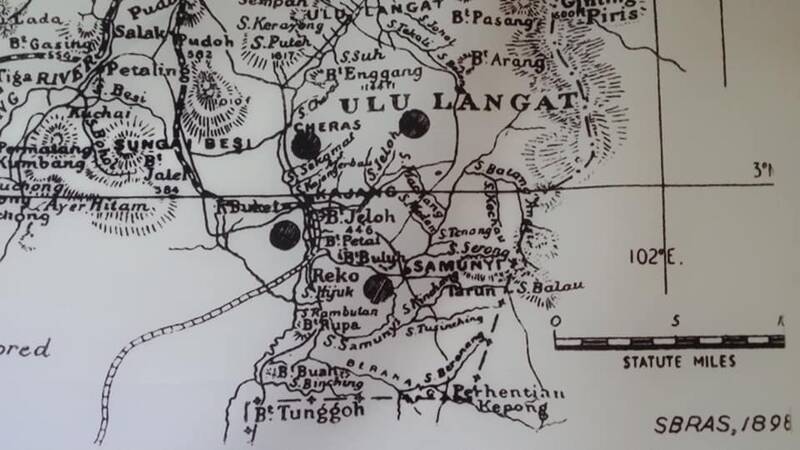

Lokasi Rekoh: “Bila saya baca buku A History of Selangor 1766-1939 oleh J.M. Gullick, saya mendapat maklumat bahawa pada akhir abad ke-19 yang lalu, di hujung Jalan Reko, berhampiran dengan setesyen komuter Bandar Baru Bangi dan UKM yang ada sekarang, ada sebuah pekan kecil bernama Rekoh. Nama Rekoh ini ada dalam peta daerah Ulu Langat (sekarang Hulu Langat) abad ke-19. Sebuah sungai kecil berhampiran dengan UKM dan berhampiran dengan bekas tapak pekan Rekoh sehingga sekarang masih bernama Sungai Rekoh.” (Andin Salleh @ Mohd Salleh Lamry, 2012: |"Dari mana asal nama Jalan Reko?").

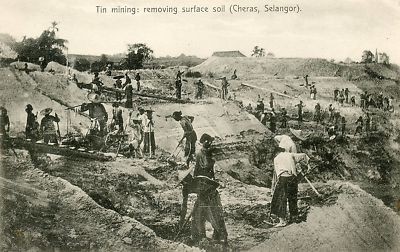

“Kajang started as a market place in 1860s where goods and produce were exchanged. Exploration for tin had been the main attraction in pulling migrants from Sumatra and Hakka labourers into Hulu Langat. Earliest recorded site of tin mining was at Rekoh, about 4 km from present Kajang. This is how Jln Reko, the road leading to UKM got its name. Frank Swettenham visited Rekoh in 1875 described the town had been a glorious place.” (Kajang Heritage Centre乌鲁冷岳社区文物馆, 21 April 2020: |"Kajang, a Tin Mining Town").

“Lee (Kim Sin) said much of Kajang’s history dating back to 1850s had been lost – Reko, the oldest settlement traced here, had “the best shops and houses of the time” according to the first British High Commissioner of Malaya Sir Frank Swettenham, but none of that can be seen now.” (Yip Yoke Teng @ The Star, 28 Jan 2019: |"Modern look is a defaced facade").

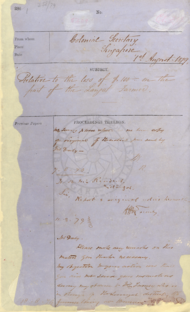

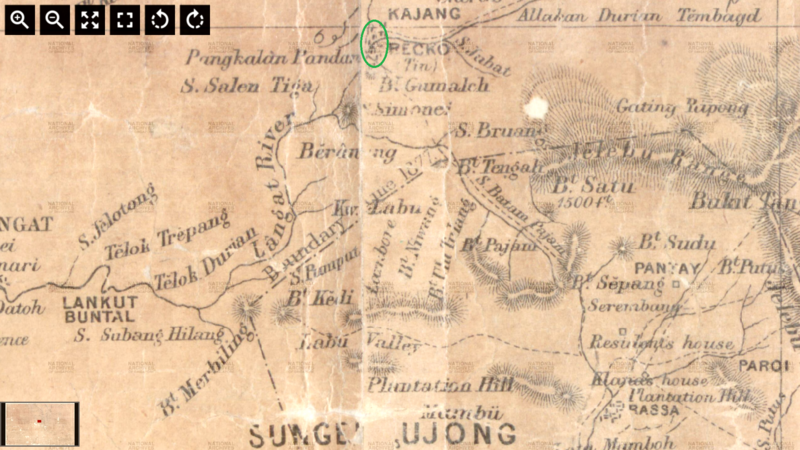

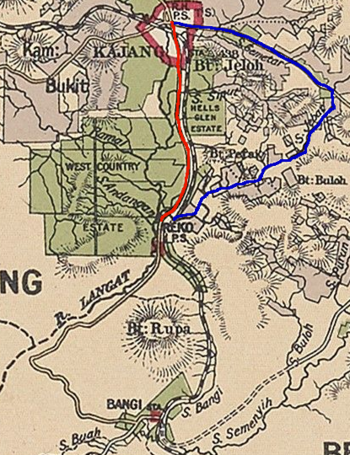

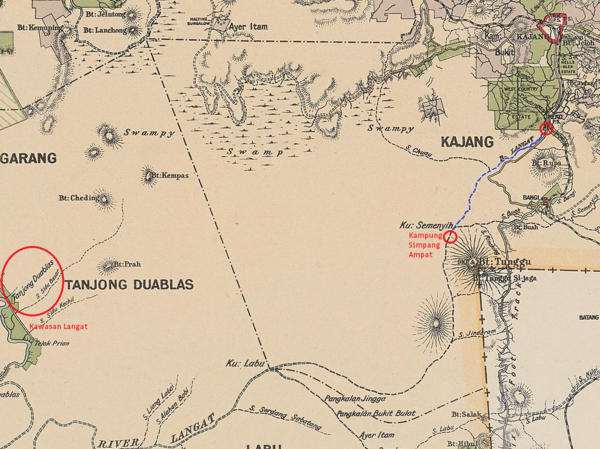

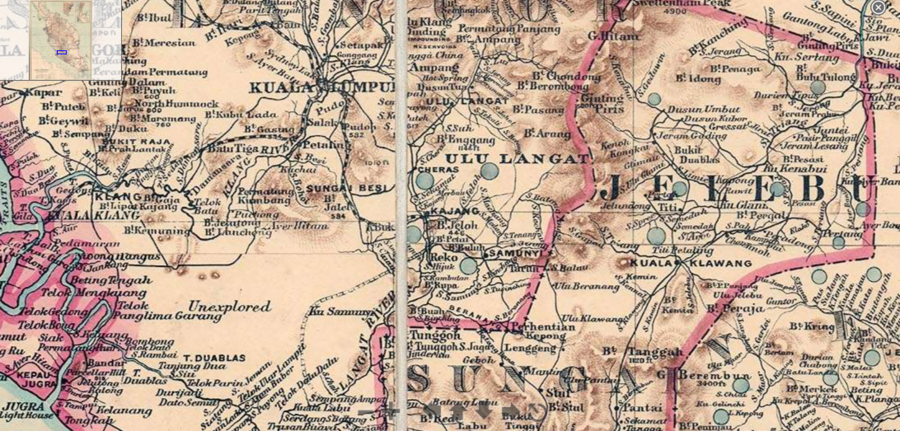

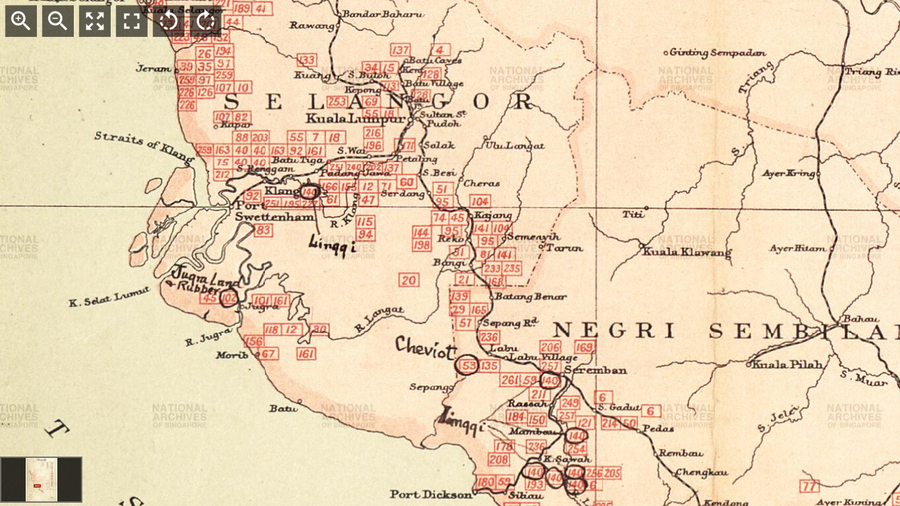

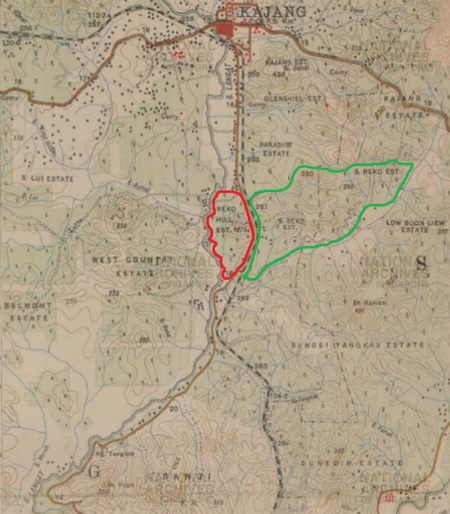

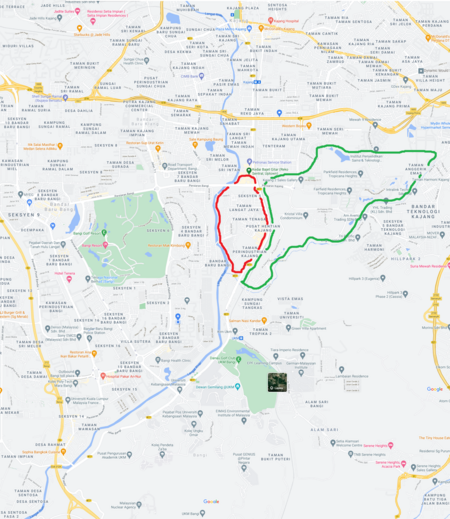

Lokasi Rekoh (sekitar bulatan hijau), 1904 dan kini.

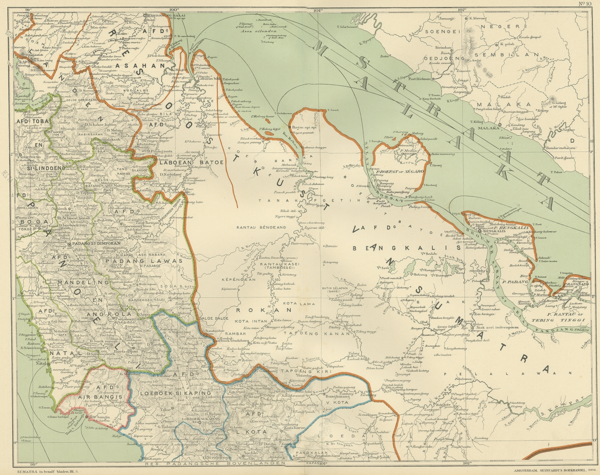

Kiri: Peta tahun 1904 (Edinburgh Geographical Institute, 1904 @ Yale University Library - Digital Collections: |"Selangor, Federated Malay States, 1904 / John Bartholomew & Co ; W.T. Wood, chief draftman").

Kanan: Peta kini (Mapcarta).

1580-1799: Penerokaan Warga Temuan

Sebagaimana keseluruhan kawasan negeri Selangor amnya, pada mulanya Kajang dan kawasan sekitarnya diterokai dan didiami oleh masyarakat Temuan (Jabatan Kemajuan Orang Asli (JAKOA): |"Suku Kaum Orang Asli Semenanjung Malaysia"). Menurut suatu sumber lisan: “Menurut sumber lisan, Jalan Reko mendapat nama disebabkan kawasan ini dahulunya terdapat banyak buah 'serengkoh'/'serengkung' iaitu buah dari sejenis pokok renik di kawasan ini. Orang asli dari suku Temuan yang mula-mula meneroka kawasan ini telah menamakannya 'Rekoh'. Kini, setelah melalui perubahan masa, perkataan 'Rekoh' telah menjadi 'Reko' sahaja.” (Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Jalan Reko, 2020: |"Wawasan Edisi ke-24: SEJARAH SEKOLAH", m.s.15).

Antara tahun-tahun penerokaan sekitar Kajang yang ada disebutkan:-

- 1580: “Perkataan Kajang lahir daripada beberapa sumber berikut : Pendapat Pertama : Adalah dipercayai Kajang telah diterokai oleh orang-orang suku Temuan kira-kira tahun 1580 lagi. Suku inilah yang memberi nama Kajang berdasarkan sejenis mengkuang hutan yang digunakan untuk membuat atap yang tumbuh dengan banyaknya di kawasan itu.” (Majlis Perbandaran Kajang, 2013: |"Asal-Usul Nama Kajang").

- 1709: “Terdapat beberapa cerita lisan berkenaan dengan penerokaan awal pekan Kajang dan kawasan sekitarnya. Menurut orang-orang tua, Kajang dan kawasan sekitarnya sebelum didatangi peneroka-peneroka dari luar adalah merupakan kawasan kediaman orang-orang asli dari Suku Temuan. Menurut seorang pengkaji sejarah tempatan En. Shahabudin Ahmad, Kajang telah diterokai pada tahun 1709 oleh orang-orang asli yang berpusat di Klang. Pada waktu itu Klang diperintah oleh orang-orang asli yang ketuanya dipanggil Batin Seri Alam. Ketua ini mentadbir di Klang kerana ketika itu hutan ini adalah pusat pentadbiran bagi orang-orang asli. Klang mempunyai jajahannya yang tersendiri yang ditadbirkan oleh 3 orang anak kepad Batin Seri Alam.” (Majlis Perbandaran Kajang: |"Info Kajang"). Ada sumber yang mengatakan nama “Kajang” tercipta di pekan Rekoh, yang telah pun wujud sebelumnya: “Ada juga sumber-sumber lain yang menerangkan asal kejadian Kajang. Sumber tersebut menyatakan bahawa suatu ketika dulu terdapat dua orang sahabat menaiki sampan melalui Sungai Langat untuk pergi ke Pekan Reko. Mereka adalah terdiri dari seorang Melayu dan seorang Asli yang mendiami kawasan Reko. Apabila sampai ke Kajang, ( ketika itu belum bernama kajang ), hujan turun dengan lebatnya. Orang Melayu mengajak rakannya ' berkajang ' di situ. Menurut cerita itu ' berkajang ' bagi orang Melayu ialah berteduh, tetapi orang Asli tersebut memahami ' berkajang ' itu sebagai bertikam. Disebabkan salah faham akan maksud rakannya itu maka orang Asli terus menikam rakannya. Dengan perisiwa bertikam itu maka tempat itu dinamakan Kajang.” (MAJLIS PERBANDARAN KAJANG (MPKj), 2006: |"SEJARAH KAJANG").

- 1799: “Terdapat beberapa versi tentang asal-usul Kajang. Hampir semua hipotesis mengenai kewujudan Kajang bertitik-tolak daripada etimologi berdasarkan nama pondok berkajang atap mengkuang yang didirikan oleh peneroka asal. Satu versi mengutarakan bahawa Kajang telah diterokai oleh 'orang asli' suku Temuan pada kira-kira 1580 (versi lain pada 1799) dan merekalah yang menamakan tempat itu 'Kajang'. Varian lain mengisahkan bahawa peneroka itu adalah seorang ketua orang asli bernama Batin Seri Alam atau Batin Berenggai Besi, dari Kelang atau Sungai Ujong.” (Abdur-Razzaq Lubis, 2021: "Tarikh Raja Asal: Derap Perantauan Kaum Mandailing dari Sumatra ke Tanah Semenanjung", m.s.224-225).

CATATAN: “Catatan pada laman web tersebut (Majlis Perbandaran Kajang) diambil daripada pengkaji sejarah tempatan Shahabudin Ahmad, 'Asal Nama Kajang Dan Sekitarnya', Minggu Sejarah Negeri Selangor 16-18 Julai, 1975, Persatuan Sejarah Malaysia Cawangan Selangor (Buku Cenderamata).” (Abdur-Razzaq Lubis, 2021: "Tarikh Raja Asal: Derap Perantauan Kaum Mandailing dari Sumatra ke Tanah Semenanjung", m.s.225).

Selain Hulu Langat, Selangor, terdapat beberapa petempatan di sekitar rantau ini yang turut dinamakan sebagai “Rekoh”. Kebanyakannya terletak di kawasan pedalaman dan diduduki oleh peribumi tempatan:-

| Negara | Negeri | Mukim/Daerah | Petempatan | Penduduk | Rujukan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malaysia | Pahang | Lipat Kajang, Temerloh | Kampung Paya Rekoh | Jah Hut, Semoq Beri | Jabatan Perancangan Bandar dan Desa Negeri Pahang, 2018: |Penerbitan -> Profil Daerah -> PROFIL DAERAH PAHANG 2018, m.s.46 Nor Baiti binti Mustafa, 2013: |"Tradisi dan kepercayaan orang Asli Jah Hut di Kampung Penderas, Temerloh", m.s. 6 |

| Malaysia | Johor | Masai, Pasir Gudang | Kampung Rekoh, Sungai Rekoh | ? | Majlis Bandaraya Pasir Gudang: |"Ketua Kampung" Sunway University, 28 September 2021: |"River restoration by Sunway College JB students"). |

| Thailand | Narathiwat | Sukhirin / Su-ngai Padi | Rekoh | ? | Sekitar Kampung Sega (kini sekitar Su-ngai Padi) dan Momang (kini sekitar Sukhirin): “Leaving Kampong Sega about 8.30 a.m. we rode to Rekoh, where I got down to stretch my limbs by walking over the Pass of Dan Popoh. It was about three miles long, and gave us a very pretty walk through moderately open jungle, the track continually crossing and recrossing streams, as it so frequently does in these parts. The path itself would have been a good one, but for one bad swampy patch, where it led through bamboo scrub on the Momang side of the divide.” (C.A. Gibson-Hill, W. W. Skeat & Dr. F. F. Laidlaw @ Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society Vol. 26, No. 4 (164), 1953: |"The Cambridge University Expedition to the North-Eastern Malay States, and to Upper Perak, 1899 - 1900", m.s.92). |

| Indonesia | Kepulauan Riau (Kepri) | Desa Penaga, Teluk Bintan, Pulau Bintan | Kampung Rekoh | ? | Antara News Kepri, 20 Julai 2023: |"Warga Kampung Rekoh Bintan ziarah makam Datuk Julong pada 1 Muharram". |

1820-an: Perlombongan Orang Rawa

Menjelang tahun 1820 (sezaman dengan Raja Busu di Lukut), Juragan Abdul Rahman, seorang pedagang di Selat Melaka, telah membawa sekumpulan orang Rawa ke Linggi. Menantunya Datuk Muda Katas memiliki 5 buah lombong di Rembau dan Sungai Ujong. Menurut Khoo Kay Kim, beliau telah mengeksport hasil timah terus ke London melalui Hong Kong, tanpa melalui Singapura atau Pulau Pinang. Orang Rawa dibawa masuk bekerja lombong di sekitar Sungai Linggi (dahulu dikenali sebagai Batang Penar), menggunakan kaedah lampan (perlombongan cara tradisi). Namun sebahagian daripada mereka ini bergiat dalam aktiviti lanun dan rompakan. Oleh sebab itu, bagi menjaga keselamatan awam, Datuk Muda Katas menguatkuasakan semula undang-undang sungai di Sungai Linggi, yang menyatakan bahawa tiada kapal/perahu boleh belayar dari Maghrib sehingga Subuh. Pelanggaran terhadap larangan ini dihukum mati.

Sekitar tahun 1825-1826, Raja Labuh telah menggantikan Yamtuan Lenggang sebagai Yamtuan Besar Negeri Sembilan. Beliau bersikap prejudis terhadap orang Rawa, kesan pengalaman berperang dengan mereka. Ketika pemerintahannya, beliau telah menyerang dan menghalau seluruh orang Rawa keluar dari kawasan Rembau. Berikutan itu, kebanyakan orang Rawa melarikan diri ke bahagian utara, di sekitar Sungai Langat, meliputi daerah Rekoh, Beranang, dan Semenyih. Akibat daripada tindakan ini, beliau kemudiannya telah dimakzulkan (diturunkan takhta).

(Sumber: Mohd Khairil Hisham Mohd Ashaari, 23 September 2023: "Wacana Sejarah Hulu Langat 2023: Peranan Syed Abdul Rahman di Rekoh Semasa Perang Rawa 1848: Berdasarkan Laporan Douglas").

Menurut sumber-sumber lain:-

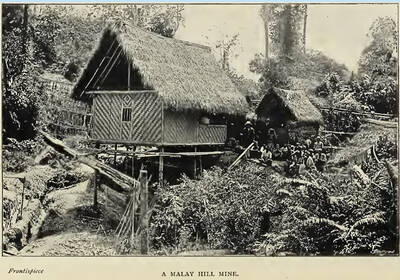

“Aktiviti melombong bijih timah di Kajang bermula di satu kawasan iaitu Reko atau Rekoh yang kini dikenali Kampung Sungai Tangkas yang menjadi daerah paling awal menjalankan aktiviti itu berbanding Kuala Lumpur. Di situ (Reko atau Rekoh) terdapat lombong dan masyarakat Mandailing tinggal di kawasan berkenaan. Orang Mandailing mengetuai aktiviti melombong bijih timah dan menjadi masyarakat pertama menjalankan aktiviti itu sekitar lewat 1840-an atau awal 1850-an.” (Lee Kim Sin @ Harian Metro, Ogos 11, 2017: |"Bijih timah jutaan tahun").

“In Ulu Langat as in many parts of the Malay States, the first stir of commercial activity began with tin mining. An American prospector probably attempted mining for tin at Reko near Kajang in the 1840s (Wong, 1965: 32). This venture was soon abandoned and taken over by some Chinese.” (Voon Phin Keong @ Malaysian Journal of Chinese Studies, Volume 2, No.2, 2013: |"Transforming the Development Frontier: Chinese Pioneers in the Ulu Langat District of Selangor, Malaysia", m.s.7-8).

Lombong lampan (Kinta Tin Mining Museum, 10 April 2021: |"Mining method: Lampan (Ground Sluicing)").

1830-an: Pembukaan Kajang

Sementara itu, sekitar tahun 1830-an, terdapat beberapa riwayat pembukaan Kajang (di sebelah utara Rekoh), melibatkan To' Lili (Bugis dari Riau), dan Raja Berayun (dari Mandailing).

MAKLUMAT LANJUT: 1830-an: Pembukaan Kajang

1830-an: Pemukiman Raja Berayun

Latar Penghijrahan: Perang Padri (1816-1833)

Sejarah awal Raja Berayun (serta petempatan pertamanya, Rekoh) boleh dijejaki mulai dengan penghijrahan golongan Mandailing dari Sumatera pasca Perang Padri (1816-1833):-

“Sewaktu Perang Padri (1816-1833) berkecamuk di Sumatra, angkatan Minangkabau menyerbu Mandailing-Natal, kampung halaman bangsa Mandailing. Di mana-mana saja berlaku penjarahan dan kerusakan harta benda. Pihak kolonial Belanda melancarkan pula sistem eksploitasi ekonomi yang menyebabkan rakyat lebih melarat, sengsara dan miskin-papa.

Lantaran situasi yang tidak lagi dapat menjamin kelangsungan hidup, mereka terpaksa pindah secara besar-besaran ke Malaysia Barat kini atau Selangor khususnya yang disebut mereka sebagai “Kolang”. Perpindahan massal mereka itu dalam abad 19 merupakan pola migrasi yang mendekati proporsi exodus.

Orang Mandailing yang sampai di Selangor (Kolang) mendirikan pemukiman , “mamungka huta”, mengikut istilah mereka di pedalaman negeri Selangor. Bahagian pesisirnya, yang telah didiami oleh etnik Nusantara yang lain, sedapat-dapatnya dihindari. Perbukitan dan lembah yang menghijau, cuaca yang sejuk menyegarkan seperti di Luat Mandailing, keadaaan yang aman di pedalaman merupakan salah satu faktor yang menarik mereka tinggal di tempat yang jauh dari pesisir. Salah satu pemukiman keturunan suku Mandailing di pedalaman terdapat seputar Kajang. Pemukiman ini tekenal dengan nama Sg Kantan yang mungkin berupa kependekan Pakantan,suatu huta Mandailing hampir Kotanopan di Mandailing Julu dan yang warganya mayoritas Marga Lubis.”

(Sumber: Haji Hanafiah Kamal Bahrin Lubis, 23 Ogos 2014: |"HORAS ! SEPUTAR DAN BERPUTAR-PUTAR DI JALAN RAJA ALANG,KAJANG,SEL.").

“The Padri raids and invasions into Rao, Mandailing and Angkola, Padang Lawas and the 'Bataklands' (circa 1816-1831), as well as Padri occupation (circa 1820-1835), resulted in the flight of political and economic refugees, as well as forced migration through slave trafficking. Notable events included the Padri destruction of Panyabungan in 1825, and the major Padri invasions which were carried northwards to the Toba lands in 1827 and 1829. Raja Barayun, who hailed from Pidoli Lombang near Panyabungan, could have migrated after 1825 following the devastation of his homeland.” (Abdur-Razzaq Lubis, 2018: "Sutan Puasa: Founder of Kuala Lumpur", m.s.125).

Penghijrahan

“Dulu “Recko ” merupkan satu lagi pemukimannya Mandailing seputar Kajang (kini Reko) .Raja Borayun ,Pendiri Kajang,pada suatu waktu,pernah menjadikan “Recko”basis ataupun bentengnya di pinggir Batang/Sungai Langat.Di sini telah bermukim warga imigran Mandailing yang substansial sekitar pertengahan abad 19 dahulu.

…

Pada umumnya turunan Mandailing marga Nasution dan Lubis tinggal di seputar Bandar Kajang, di samping marga Harahap dan Siregar (*Serigar). Masyarakat Mandailing itu dipimpin oleh Raja Borayun putera Mangaraja Tinating ,marga Nasution ,asal Pidoli Lombang, Mandailing Julu. Salah seorang cucu-cicitnya, Raja Ayub putra Raja Harun putra Raja Hidayat putera Raja Borayun menetap di rumah pusaka yang dibina Raja Harun di Lot 6747, Batu 14, Jalan Cheras, 43000 Kajang. Pusara Encik Nyonya Cantik, isteri Raja Borayun,ompung godang Raja Ayub,terdapat di Perkuburan Islam, Batu 14, Kajang.

Seperti dicatat sebelumnya, Raja Borayun merupakan namora atau raja Mandailing yang menjadi pimpinan komunitas Mandailing di Kajang dalam abad 19. Beliau dianugerahi gelar Tengku Panglima Besar oleh Sultan Abdul Samad yang mulai bersemayam di atas takhta Selangor pada tahun 1857.Raja Mandailing ini, turunan Mangaraja Saoloon Pidoli Lombang , merupakan pemain yang cukup penting di atas panggung politik Negeri Selangor dalam abad 19.

Besar kemungkinan, Raja Borayun sudah menetap di Kolang/Selangor sebelum Sutan Puasa (Sutan Na Poso) sampai di Kolang dari Tobang, Mandailing Julu kira-kira dalam tahun 1830-an. Kemungkinan juga seorang tokoh Mandailing yang lain, Ja Marabun Rangkuti (Bendahara Raja gelar Melayunya) mendampinginya dalam perjalanan ke Kolang. Bendahara Raja ternyata pertama kali menetap di Selangor sewaktu Sultan Muhammad bersemayam (1826-1857) (A.R. Lubis)”

(Sumber: Haji Hanafiah Kamal Bahrin Lubis, 23 Ogos 2014: |"HORAS ! SEPUTAR DAN BERPUTAR-PUTAR DI JALAN RAJA ALANG,KAJANG,SEL.").

Peta sebahagian Sumatera (Riau dan sekitarnya) dan Tanah Melayu (termasuk Mandailing-Natal, Rokan (Rambah-Tambusai), dll, sekitar 1900-an, sebagai ilustrasi perantauan orang-orang Sumatera ke Tanah Melayu: “Antique map of the East Coast of Sumatra. Also depicting the Strait of Malacca. This map originates from ‘Atlas van Nederlandsch Oost- en West-Indië’ by I. Dornseiffen.” (Seyffardt’s Boekhandel, Amsterdam, 1904 @ Bartele Gallery: |"MAP OF THE EAST COAST OF SUMATRA – DORNSEIFFEN C.1900").

LATAR PERISTIWA: Raja Berayun / Borayun / Brayun / Jabarayun

LATAR PERISTIWA: Raja Alang bin Raja Berayun

1848: Perang Rawa

WS-HL-2023-S2: Peranan Syed Abdul Rahman di Rekoh Semasa Perang Rawa 1848: Berdasarkan Laporan Douglas (Perbadanan Perpustakaan Awam Selangor, 23 September 2023: Sumber rakaman asal (tidak lagi disiarkan)).

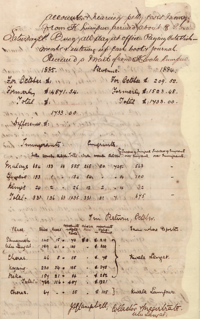

Ringkasan pembentangan: WS-HL-2023-S2: Peranan Syed Abdul Rahman di Rekoh Semasa Perang Rawa 1848: Berdasarkan Laporan Douglas.

Sekitar tahun 1848, Dato Kelana Sendeng, ketika itu penghulu Sungai Ujong, juga seorang yang bersikap prejudis terhadap orang Rawa. Dalam suatu kes yang tidak dapat dikenalpasti puncanya, beliau telah menangkap 3 orang Rawa lalu dijatuhkan hukuman mati. Pemimpin Orang Rawa di bawah Raja Berayun di Rekoh memohon Dato Kelana Sendeng untuk melepaskan atau meringankan hukuman, namun ditolak. Ini mencetuskan kemarahan orang Rawa di situ, dan sentimen ini telah merebak ke Klang dan juga Pahang.

Rentetan itu, Raja Berayun telah menemui Syed Abdul Rahman (beliau juga tinggal di Rekoh ketika itu), untuk mendapatkan bantuan dalam serangan terhadap Dato Kelana Sendeng. Syed Abdul Rahman ketika itu adalah musuh Dato Kelana Sendeng (sebelum ini beliau ingin jadi Dato Kelana, tetapi gagal). Beliau bersetuju membantu (kemungkinan dari sudut kewangan), dengan syarat orang Rawa mesti menyokong beliau untuk menjadi Dato Kelana bagi menggantikan Dato Kelana Sendeng kelak. Maka perlakulah perang saudara Rekoh-Sungai Ujong (perang besar bagi orang Rawa, kerana menentang keseluruhan luak, bukan Dato Kelana Sendeng saja).

Sementara itu, sebilangan orang Rawa di bawah Tuanku Tambusai di Rasah, Sungai Ujong, tidak menyokong orang Rawa Syed Abdul Rahman di Rekoh, lalu membantu Dato Kelana Sendeng. Pada akhirnya, orang Rawa Rekoh kalah, dan Syed Abdul Rahman pun kembali ke Rekoh. Penglibatan awal Syed Abdul Rahman dalam konflik ini mungkin ada kesinambungannya dengan konflik tahun 1874 yang menyebabkan perjanjian beliau dengan British pada tahun 1874, diikuti Pemberontakan Rekoh (Rekoh Wreckage) pada tahun 1875 yang diakhiri dengan perjanjian damai dengan Sultan Abdul Samad, seterusnya perjanjian penyerahan Rekoh dan Semenyih (kepada Selangor) serta Lukut (kepada Sungai Ujong) pada tahun 1878.

(Sumber: Mohd Khairil Hisham Mohd Ashaari, 23 September 2023: "Wacana Sejarah Hulu Langat 2023: Peranan Syed Abdul Rahman di Rekoh Semasa Perang Rawa 1848: Berdasarkan Laporan Douglas").

Kiri: Syed Abdul Rahman, 1879 (Arkib Negara Malaysia 2001/0026749W, 31/12/1879: |"DATO KELANA PETRA SYED ABDUL RAHMAN OF SUNGAI UJONG, SINGAPORE; C.1879").

Kanan: “Rumah kediaman Datuk Kelana Sungai Ujong, Sayyid Abdul Rahman pada tahun 1874. (Arkib Negara Malaysia)” (Legasi Pemikir - LEKIR, 24 Januari 2021: "Rumah kediaman Datuk Kelana Sungai Ujong").

Dari sumber-sumber lain:-

“Menjelang tahun 1848, Raja Borayun berhasil menjalin hubungan yang rapat dengan pembesar-pembesar Bugis yang berpengaruh di istana Selangor. Dalam pada itu beliau berhasil menggalang angkatan hulu-balangnya yang merupakan kesatuan kombatan yang kuat. Menyadari posisinya yang bertambah kuat itu, pada tahun 1848 Raja Borayun menyerang Sg. Ujong (Seremban) sebab Dato Klana Sendeng tidak membayar “duit nyawa” (blood money) sejumlah $400 atas terbunuhnya seorang anak buahnya. Tentu saja masuk akal serangan itu diatur dan dilancarkan dari “Recko”, pangkalan dan pemukiman Mandailing di Selatan Kajang yang tidak jauh dari Seremban.”

(Sumber: Haji Hanafiah Kamal Bahrin Lubis, 23 Ogos 2014: |"HORAS ! SEPUTAR DAN BERPUTAR-PUTAR DI JALAN RAJA ALANG,KAJANG,SEL.").

Peristiwa serangan Raja Brayun terhadap Datoh Klana Sendeng, menurut anak beliau, Raja Alang (melalui wawancara dan tulisan J.C. Pasqual): “At this time Raja Brayun, a Mendeleng from Sumatra, invaded Sungei Ujong and attacked Datoh Klana Sendeng, because a friend of Raja Brayun was murdered and Datoh Klana Sendeng refused to pay the blood money of $400 according to the 'adat' Malayu. On the side of Raja Brayun there was Panglima Garang and Panglima Si Gara, both 'invulnerable' and fierce warriors, besides 500 fighting men. But he was defeated although he had bribed one of Datoh Kalan Sendeng's men with $3,000 to burn the granaries and blow up a powder magazine. Raja Brayun then retired to Recko, a village on the Langat river a short distance upstream from Kajang, and invited Raja Abdulsamad to live with him. He built a stockade at Recko and had a large force of fighting men who lived by robbery and raiding Sakais to sell them into slavery.” (The Straits Times, 11 November 1934, Page 21: |"WHEN COCKFIGHTING WAS THE RAGE").

“Thomas Braddell in his note on the history of Negeri Sembilan enclosed with SS Despatch to the CO dated 29th December 1874, reveals the involvement of the Rawa (Rao) and Mandailing in the Rawa War of 1848. The latter were in Sungai Ujong (Seremban today) following the wake of the Padri War (1816-1833).

” The Rawa disturbances in 1848 are of sufficient importance to justify a few words giving an account of another and a most serious misfortune to the Sungai Ujong mine.

“ The Rawa are an adventurous people with a strong turn for trade, living to the north east of the Pagarooyong (Menangkabowe) district, in the middle of Sumatra. They have long been in the habit of trading to the Peninsula, and have established Colonies in several places, the most important of which was at Pahang, where they almost monopolized the trade. The superiority of these people over the ordinary Malay give rise to jealousies which require them to be on their guard, and to combine for mutual protection, so that when any of the tribe are injured the rest are bound to assist in protecting them, a feature in their character which adds to the dislike of them entertained by the Malays; but being like the Chinese, good colonists, they are allowed to remain in the Malay countries.

” Causes of. - A number of the tribe had settled in Sungei Ujong, and were getting the chief portion of the local trade in their hands where three of them were put to death by the Klana for an alleged offence. The justice of the execution was denied by the trio, and they determined to exact vengeance. Assistance was sent for to Pahang, their head quarters, and open war was declared. This was said to have been the pretext for the war, but the truth probably was, that the many differences and jealousies between the two races had brought matters to such a state that it required very little to bring on a war.

“ Result of. - The Rawa proved their individual superiority over the Malays during the war. But being few in numbers and distant from their resources they were at last obliged to retire; and they have not since been allowed to return to the country. The Rawas who are now in Sungei Ujong are said to be Tamoosai Rawas, and do not mix with the others, Rawa Ulu (or up country Rawas); in fact the Tamoosais sided with the Klana.”

Here in this passage we have the first mention of the presence of the “Tamoosai” in the Peninsula in the second quarter of the 19th century. There were probably two groups of people from Rao - the Mandailings and the Rao. Rao is the frontier country between Minangkabau and Mandailing. The Rao or “orang Rawa” as they are known in the Peninsula and in East Sumatra. The “Tamoosai Rawas” were Rawa from Tambusai, while Rawa Ulu (or up country Rawas) were probably Mandailing, whose homeland was to the north of Rao. Of course, this does not discount the Tambusai's presence, a distinct group in themselves.

The Mandailing involvement in the “Sungei Ujong” affair was confirmed by J.C. Pasqual who wrote about the episode in 1930s based on an account from “Raja Allang ibni Raja Brayun, who was a Forest ranger of the Ulu Langat district in the late 'eighties (1880's)”. He implied that the Mandailings were not on the side of Dato' Klana but against him.

“ At this time Raja Brayun, a Mendeleng from Sumatra, invaded Sungei Ujong and attacked Datoh Klana Sendeng, because a friend of Raja Brayun was murdered and Datoh Klana Sendeng refused to pay the blood money of $400 according to 'adat' Malayu. On the side of Raja Brayun there was Panglima Garang and Panglima Si Gara, both 'invulnerable' and fierce warriors, besides 500 fighting men. But he was defeated although he had bribed one of Datoh Klana Sendeng's men with $3,000 to burn the granaries and blow up a powder magazine. Raja Brayun then retired to Recko, a village on the Langat river a short distance upstream from Kajang, and invited Raja Abdulsamad to live with him. He built a stockade at Recko and had a large force of fighting men who lived by robbery and raiding Sakais to sell them into slavery.”

Mandailings as well as Rawas raided Orang Asli and sold them into slavery. This is not to say that historically all Mandailings and Rawas were a party to this. Other Mandailings were also noted in British records as having employed Orang Asli.“

(Sumber: Abdur-Razzaq Lubis dll @ mandailing.org, 2004-2006: |"The Rawa War of 1848").

1853: Tempat Perlindungan Raja Abdul Samad

Sekitar tahun 1853, Rekoh menjadi tempat perlindungan Raja Abdul Samad (10 tahun sebelum pertabalannya sebagai Sultan Abdul Samad pada tahun 1863):-

“Namun pada tahun 1853, istana Selangor digemparkan dengan kemangkatan mengejut ketiga-tiga putera sultan yang sedang berselisihan faham mengenai takhta diraja Selangor tanpa diketahui sebab-musababnya. Namun begitu tidak lama selepas itu sebuah angkatan tentera Bugis Selangor telah diarahkan menangkap anak saudara Sultan Muhammad Shah yang bernama Raja Abdul Samad yang juga merupakan menantunya setelah Raja Abdul Samad dikahwinkan dengan puteri baginda yang bernama Raja Aftah. Raja Abdul Samad pada masa itu tinggal di Langat bersama dengan bapanya Raja Abdullah bin Sultan Ibrahim Shah yang diberikan hak untuk menjaga dan mengutip cukai di sana. Apabila mendapat tahu dirinya diburu, Raja Abdul Samad pun meninggalkan Langat dan berlindung kepada Jabarayun di Kampung Reko. - The Sunday Times, 2 Dec 1934.

Apabila mendapat tahu Raja Abdul Samad sedang berlindung dengan Jabarayun di Ulu Sungai Langat, Sultan Muhammad Shah memberi amaran dan memerintahkan Jabarayun agar jangan campur tangan dengan memberi perlindungan kepada Raja Abdul Samad. Tetapi Jabarayun langsung tidak mengendahkannya. Lantaran itu Sultan Muhammad Shah pun mengarahkan angkatan tentera Bugis supaya bersiap-sedia dengan 500 perahu perang di Kelang untuk menyerang Jabarayun di Kampung Reko.

‘Recko was located in Selangor on the Langat River, but within a few miles of the Sungei Ujong border.’ (121) – Burns (The Journal of J.W.W. Birch)

Apabila mendapat tahu angkatan tentera Bugis Selangor sedang dalam perjalanan untuk menyerang Kampung Reko, Jabarayun bersiap-sedia dengan 300 pengikutnya yang bersenjatakan kapak dan beliung. Jabarayun dan panglima-panglimanya merancang untuk menebang pokok-pokok tinggi di tengah hutan untuk merentangi Sungai Langat dan menghalang kemaraan perahu-perahu angkatan tentera Bugis. Dengan cara itu orang-orang Jabarayun boleh meluru untuk membunuh tentera-tentera Bugis yang terperangkap di tengah-tengah sungai itu.

Rombongan tentera Bugis itu bertolak dari Kelang dan memudiki Sungai Langat sehingga sampai dekat Kampung Dengkil sebelum berpatah balik ke Kelang secara tiba-tiba tanpa diketahui sebabnya. Akhirnya tiada serangan yang berlaku. Sejak itulah nama Jabarayun menjadi terkenal dan berpengaruh serta sangat ditakuti oleh pembesar-pembesar Bugis Selangor.”

(Sumber: Mohamed Azli bin Mohamed Azizi @ Lembaga Adat Mandailing Malaysia (LAMA): |"Kuala Lumpur Siapa Punya?").

“Kuasa dan wibawa Raja Borayun makin terkonsolidasi setelah beliau berhasil memukul mundur angkatan yang bakal menyerangnya di “Recko” tanpa tempur berkuah darah. Awalnya Raja Borayun dimurkai Sultan Muhammad sebab menjalin persahabatan yang akrab dengan Abdul Samad, keponakan dan menantu Sultan. Lantaran tidak menghiraukan kemurkaan Sultan, beliau menghadapi serangan angkatan Istana Selangor yang kiranya akan menghabisinya sama sekali.

Angkatan istana sejumlah 500 buah perahu digalang di Kajang. Raja Borayun yang berada di “Recko” akan diserang dari sungai. Mujurlah Strategi Raja Borayun berhasil mematahkan serangan yang berbahaya dan mematikan itu.Kombatan Mandailing yang heroik sejumlah 300 orang menebang pohon kayu dan merintangkannya di tengah sungai. Apabila perahu yang membawa angkatan penyerang terbentur di tengah sungai, mereka akan diamuki dan dibantai semuanya. Menyadari peristiwa pembantaian berkuah darah yang bakal menimpa, para penyerang puntang-panting mendayung perahu kembali ke Kajang.”

(Sumber: Haji Hanafiah Kamal Bahrin Lubis, 23 Ogos 2014: |"HORAS ! SEPUTAR DAN BERPUTAR-PUTAR DI JALAN RAJA ALANG,KAJANG,SEL.").

Peristiwa serangan Sultan Muhammad terhadap Raja Brayun di Rekoh, menurut anak beliau, Raja Alang (melalui wawancara dan tulisan J.C. Pasqual): “In the reign of Sultan Mahomad he was afraid of Raja Abdulsamad (afterwards Sultan), his cousin, who he suspected would betray him and usurp the throne, and for this reason he ordered the arrest of Abdulsamad who field(fled) to Kajan(g), a village higher up the Langat river, and settled there. At this time Raja Brayun, a Mendeleng from Sumatra, invaded Sungei Ujong and attacked Datoh Klana Sendeng, because a friend of Raja Brayun was murdered and Datoh Klana Sendeng refused to pay the blood money of $400 according to the 'adat' Malayu. On the side of Raja Brayun there was Panglima Garang and Panglima Si Gara, both 'invulnerable' and fierce warriors, besides 500 fighting men. But he was defeated although he had bribed one of Datoh Kalan Sendeng's men with $3,000 to burn the granaries and blow up a powder magazine. Raja Brayun then retired to Recko, a village on the Langat river a short distance upstream from Kajang, and invited Raja Abdulsamad to live with him. He built a stockade at Recko and had a large force of fighting men who lived by robbery and raiding Sakais to sell them into slavery. When Sultan Mahomad heard that Abdulsamad was living with Raja Brayun he sent a warning to Raja Brayun not to shelter Abdulsamad or have anything to do with him. As Raja Brayun paid no heed to his warning, the Sultan fitted up an expedition of 500 prahus from Kajang to attack Recko, and everybody warned Raja Brayun to be on his guard. On his part, Raja Brayun got together 300 men with axes and bliongs with orders to fell the forest across the river on hearing the report of a gun, and to run amuck and massacre Sultan Mahomad's men if they attempted to cut through the blockade. Nothing happened as the expedition returned to Kajang.” (The Straits Times, 11 November 1934, Page 21: |"WHEN COCKFIGHTING WAS THE RAGE").

1855: Pelombong dari Amerika

”…dikatakan ada orang Amerika yang telah membuka lombong bijih di Sungai Tangkas yang letaknya tidak jauh dari Rekoh dengan pengikutnya kira-kira 60 orang Orang Hitam. Akan tetapi mereka telah diserang oleh penduduk tempatan. Tiga orang orang Amerika dan setengah dozen buruh telah dibunuh dan rumah mereka telah dibakar. Pelombong yang lain berpindah untuk sementara ke Bagan Terendah, sebelum meneruskan usaha melombong di Kuala Langat.“ (Andin Salleh @ Mohd Salleh Lamry, July 18, 2013: |"Pekan Rekoh yang sudah lenyap").

Ringkasan Peristwa

“Pada akhir 1840an kira-kira sedozen orang putih Amerika bersama pengikutnya seramai 60 orang hitam (hamba Habsyi) datang ke Rekoh* (sekarang Reko berdekatan Kg. Sungai Tangkas - UKM Bangi) iaitu 6 batu dari sempadan Selangor - Sg. Ujong. Mereka memulakan operasi perlombongan yang berjaya di Rekoh. Bagaimanapun mereka tidak meminta izin dan berunding dengan Tok Perkasa (Tok Pawang Besar) yang kemudiannya mengadu hal tersebut pada Tok Bandar Lili (Pembesar Kajang) mengenai pelanggaran hak istimewanya (sebagai pembuka lombong) dan sikap kurang ajar pendatang asing membuka lombong tanpa kebenarannya. Tok Bandar Kajang bersimpati dengan beliau dengan itu beliau berpakat dan mengarahkan empat atau lima “orang Tambusai” membuat amuk. Serangan nekad itu berlaku pada waktu malam. Orang - orang Tambusai membakar rumah kongsi pelombong Amerika dan menikam apabila mereka keluar untuk cuba menyelamatkan diri. Orang - orang Tambusai berhasil membunuh tiga orang putih Amerika dan enam atau tujuh daripada kuli orang hitam mereka juga dibunuh. Yang terselamat melarikan diri dan berlindung seketika di Bagan Terendan dekat Pasangan, dan kemudiannya akhir mereka melarikan diri ke hilir ke Kuala Langat.

* Rekoh sebuah pekan perlombongan dibuka orang Melayu yang punya pekan, perkampungan, balai polis, hospital dan juga punya pengkalan yang kemudian lenyap dari sejarah, terutama apabila kuasa ekonomi perlombongan Melayu musnah apabila tamatnya Perang Saudara Selangor dan kemasukan British Selangor pada 1874. Dalam banyak catatan juga di eja sebagai Reko, Recko, Rakoh, nama tempat ini juga wujud di Sumatera Barat.

* Orang Tambusai - adalah gelaran bagi pengikut Tuanku Tambusai yang berhijrah ke Sg. Ujong dan Semenanjung daripada daerah Rokan Hulu, Riau Sumatera. Keturunan Tambusai di Hulu Langat masih menetap di sekitar Kampung Jenderam, Sg. Merab dan Kampung Bangi.

- Kisah ini punya dua versi berlainan- satu lagi adalah versi Raja Berayun mengarahkan ratusan pengikut membuat amuk pada 1850an. Sumber ini diterjemahkan dan disusun semula daripada buku Selangor Journal & Sutan Puasa Founder Of Kuala Lumpur. Catatan ajaizainal.”

(Sumber: Faizal Zainal @ Facebook Pekan Bangi, 11 Ogos 2025: "Sejarah Daerah Kita: Amuk Di Rekoh").

Sumber akhbar

- “Looking through the Selangor Journal the other day, I came upon what is perhaps the most extraordinary episode in the history of European penetration of Malaya. Somewhere about the year 1855 a party of twelve Americans and 60 Orang Hitam (negroes) sailed up the Langat river, in Selangor, took possession of the village of Reko, and began mining at a place called Sungei Tangkas. They neglected, however, to obtain the permission of the district chief, with the result that the Malays launched a night attack, killed three Americans and six or seven negroes, and set fire to the wooden house in which they were living. The survivors fled downstream and made a fresh settlement near Passangan, but after a short stay they left the Langat river and were never heard of again.” (The Straits Budget, 7 February 1935, Page 6: | "AMERICANS AT REKO").

“An American prospector started a tin mine at Rekoh in 1855. However, the locals objected as he did not possess any consent and the venture was abandoned. There were altercations and eventually, the Americans left.” (AKU BUDAK TELOK, Jun 15, 2021: |"KISAH SULTAN DAN NEGRO DI JUGRA DAN REKOH").

Sumber asal

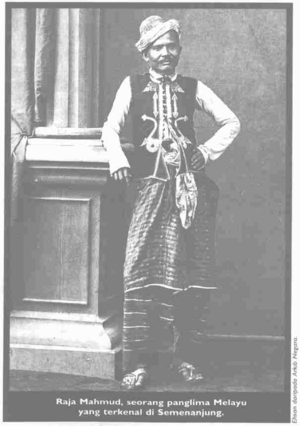

“TRADITIONS OF ULU LANGAT

The following incidents are taken from statements made by Penghulus Raja Mahmud, of Semenyih, Said Yahya, of Cheras, and Jahya of Kajang, respectively, concerning the origin of the various settlements under their charge, and may be of interest to your readers. Of course I cannot be responsible for the statements made but have collected the information as it was otherwise likely to be lost, and as it may prove of some slight assistance to some future compiler of a history of the State. …..” (1897: The Selangor Journal: Jottings Past and Present, Volume 5, hlm.305-306).

“The Penghulu of Kajang states that Kajang is about 120 years old, and that it was founded by Toh (then Inche Lili, of Rio, under authority from Sultan Mohamad ibni-el Marhum Sultan Ibrahim, who had brought him as one of his following from Rio to Selangor. …..” (1897: The Selangor Journal: Jottings Past and Present, Volume 5, hlm.306-307).

“Before this, however, about a dozen Americans, with a following of some 60 Orang Hitam (“Blacks,”) came upstream, took possession of Rekoh, and started successful mining operations at Sungei Tangkas (The date of the American settlement at Rekoh may perhaps be roughly put at 1855). As, however, they had not consulted the Toh Perkasa, otherwise known as Toh Pawang Besar (the “Great Medicine-man”), the latter sought out Toh Bandar Lili and complained bitterly of their infringement of his privilege (of “opening” mines). The Toh Bandar appeared to sympathise with him, and he therefore conspired with four or five “orang Tembusai”, who after two or three days' interval “ran amuck” at the Americans by his orders, with the result that three of the Americans, and six or seven of their native followers were killed, the attack taking place by night, so that the assailants were able without difficulty to set fire to the house (which was built of planks) and stab the inmates as they came out. The survivors fled and established themselves for a time at Bagan Terendah near Pasangan, and subsequently made their way downstream to Kuala Langat. Subsequently the Toh Pawang (Perkasa) died at about 65 years of age and was buried at the “Old Farm” (Pajak Lama), near Rekoh, leaving behind a son named Pah Sirum, who is said to live at Lengging. The deceased was of great fame throughout the country and was reputed to have the power of turning stone into ore, and vice versa.” (1897: The Selangor Journal: Jottings Past and Present, Volume 5, hlm.307).

Sumber makalah

“The Langat valley witnessed one of the most unusual episodes in the history of tin mining of this period, It began in the late 1840's with the arrival of an 'American gentleman' to inspect the thriving tin mines in Malacca territory; he went on to look at mining prospects 'in the Malayan states to the north and south,' and produced a 'very favourable' report likely to be 'duly appreciated by his enterprising countrymen, whose habit it is to plunge in medias res.'[28] However some years elapsed before 'about a dozen Americans with a following of some 60 Orang Hitam ('Blacks')' opened a mine at Sungei Tangkas near Rekoh (Ulu Langat) from which they 'got a considerable quantity of ore.' Even twenty years later their abandoned mine was 'a huge pond' with the remains of a 'good road' from the mine to Rekoh. However they did not employ the services of the 'Great Medicine-Man', a magician and diviner of 'great fame throughout the country….reputed to have the power of turning rock into ore, and vice versa.' Hell hath no fury like an expert scorned. The enraged magician did not show his prowess by converting their ore deposits into ore, but led a night attack on the house in which they lived, killing three of the Americans and half a dozen labourers; the house was burnt down. The miners moved temporarily to Bagan Terendah, but soon decided against continuing to mine in such a hostile environment and so 'made their way downstream to Kuala Langat', and thus disappeared (c.1855) from the annals of Selangor.[29]

….

28. Commercial Tariffs and Regulations and Trade of the Several States of Europe and America, together with Commercial Treaties between England and Foreign Countries, Part XXII, India, Ceylon and Other Oriental Countries, HC Papers, Vol 61, 1847-48, Cmd 974, p.734, cited by Wong Lin Ken, op.cit.,p.32, for the American prospector. It is not unlikely (but there is no evidence) that Joseph Balestier, American Consul in Singapore 1833-1852, prompted this survey, since he was active in promoting American trade, and in his later years, investment in the region. Sharom Ahmat, 'American Trade with Singapore 1819-1865', JMBRAS 38(2), 1965, and his 'Joseph B. Balestier: The First American Consul In Singapore,' JMBRAS 39(2), 1966. Balestier is quoted by name, on the trade of Malacca. in the paragraph of Cmd. 974 which precedes the reference to the 'American gentleman'. In medias res - rushing into the middle of things (from the Latin poet, Horace).

29. Swettenham visited and described the remains of the mine in March 1875. F.A.Swettenham, Sir Frank Swettenham's Malayan Journals 1874-1876, edited P.L.Burns and C.D.Cowan, Oxford University Press, Kuala Lumpur, 1975, p.212, entry of 21 March 1875. He reported (in similar terms) what he had seen in his 'Report of Her Britannic Majesty's Acting Assistant Resident at Salangore', dated 8 April 1875, enclosed with SSD 27 April 1875 (printed in Cmd 1320 of 1875). The source of the story of the pawang, Toh Perkasa, and his revenge is from 'Traditions of Ulu Langat', SJ 5, 1896-97, p.307. The initials 'W.S.' at the end of this article identify the author as W.W.Skeat, who had been District Officer, Ulu Langat, in the mid-1890's. Skeat dates the mine as c.1855. There is no direct evidence to link this venture with the prospector's report of a few years before.”

(Sumber: J.M. Gullick, 1998: "A History of Selangor 1766-1939", m.s. 39, 45-46).

Sumber Lain

Terdapat sumber yang mengatakan Jabarayun (Raja Berayun) yang mengetuai pengusiran itu:-

- “Pada tahun 1855, satu lagi pergaduhan besar telah berlaku di Kampung Reko. Menurut ceritanya, berpuluh-puluh orang putih dari Amerika telah membawa 60 hamba abdi berbangsa Negro muncul secara tiba-tiba di Kampung Reko dan memulakan aktiviti perlombongan bijih timah di Sungai Tangkas. Jabarayun sebagai ketua lanun di Kampung Reko merasa tercabar dengan kehadiran tetamu yang tidak diundang itu yang memulakan aktiviti perlombongan tanpa meminta izin dari pembesar-pembesar tempatan. Tanpa menunggu lama, Jabarayun membawa 300 pengikutnya yang bersenjatakan kapak dan beliung menyerang rombongan dari Amerika itu. Apabila diserang oleh Jabarayun dan pengikutnya, orang-orang Amerika itu segera melarikan diri menaiki sampan dari Sungai Tangkas dan hilang entah ke mana. 6 orang Amerika dibunuh dalam serangan ini. Nama gah Jabarayun menjadi semakin terkenal lagi berpengaruh di kalangan pembesar-pembesar Bugis Selangor. (212) – Burns (The Journals of F.A. Swettenham)” (Haji Hanafiah Kamal Bahrin Lubis, 23 Ogos 2014: |"HORAS ! SEPUTAR DAN BERPUTAR-PUTAR DI JALAN RAJA ALANG,KAJANG,SEL.").

- “Decades before establishment of Kajang Town, Reko/Rekoh/Recko was already an active mining town. In 1850s, a dispute was reported between the American prospector and the local Malays. The Americans fled after some lives were lost. The Mendailing migrants from Sumatra were there much earlier prospecting tin and involved in commercial activities. Their chief was Raja Brayun or Jabrayun who later became the Panglima and bodyguard of Sultan Abdul Samad. Swettenhem visited the town in 1875 and described that it must be the most established town in the area. Reko left no trace of past glory. Few people knows of its existence. The road leading from Kajang to UKM is called Reko Road.” (Lee Kim Sin, 29 Julai 2017: |"Decades before establishment of Kajang Town, Reko/Rekoh/Recko was already an active mining town.").

1857: Permulaan Pemerintahan Sultan Abdul Samad

Setelah mangkatnya Sultan Muhammad (Sultan Selangor) pada tahun 1857, Sultan Abdul Samad telah mengambil alih takhta kerajaan Selangor. Anak Pembesar Lukut ketika itu, Raja Bot bin Raja Jumaat, pernah meriwayatkan suasana ketika itu, menjurus kepada kegiatan tanaman padi tempatan yang merosot secara drastiknya:-

“I remember that the kinds of rice eaten by men in the Malay country were as follows:- (1) Javanese rice, very good in quality, with only a short stem like the present Rangoon rice, only a little smaller. (2) Siamese rice, (3) Rangoon Rice. (4) Rice From Acheen. (5) Rice from Malacca. Those were the five places which produced rice eaten in this country.

In olden times my grandfather, Sultan Muhammad of Selangor, was himself very fond of planting paddy and also rigorously insisted on all his subjects doing so too. There were tools, and men, moreover, to work. Those who were slow or who did not toil at paddy planting were punished. On the Selangor river from Teluk Penyamun, on the right bank, and on the left as far as Kampong Kedah in the interior, nothing but paddy fields could be seen in those days. I well remember that in 1273 (A.H.) the year in which Sultan Muhammad was buried, I bought Selangor rice at the rate of a hundred gantangs for $5, and paddy at the rate of a hundred gantangs for $2.50: ducks, fowls and goats were cheap, because in those days every kind of provision was plentiful and abundant.

In 1273 (A.H.) Sultan Muhammad died and was succeeded by Sultan Abdul Samad. There were then “Sawahs” in Selangor, while on the Langat river men planted “ladangs.” In 1276 (A.H.) rinderpest broke out, and it may be said that all the buffaloes in Selangor died: there remained only ten or twelve, which escaped into the jungle and became wild. These are now in the neighbourhood of Jeram. The result of this was that the Selangor “raiats” ceased working “sawahs,” having lost, as it were, the chief implement of their trade. Sultan Abdul Samad was not powerful enough to insist on the work being continued, for though he himself liked paddy planting he could not enforce it upon the “raiats” of the country.

In 1275 (A.H.) for the first time, a duty was imposed upon tin, nothing else being taxed. The duty was 20 per cent. Subsequently the truck system at the mines ceased, and within the next two years the Chinese merchants asked that the 20 per cent should be abolished, and 10 per cent, taken on tin. A tax was placed on opium, $2 a ball, and on rice, $4 a koyan. These were the three articles taxed.

The price of white Java rice was $58 to $60 a koyan. Siam rice was $3 less, while that from Rangoon was $15 a koyan. The last named was not at that time much liked by the Chinese. White Acheen rice was from $37 to $38, and red Acheen rice $27 to $28 a koyan. Malacca rice was sometimes the same price as the Javanese, sometimes as the Siamese variety. The price of tin in Malacca was within $2 or $3, more or less, of $60 a bhara, which is three pikuls. The people of Selangor rarely then went as far as Singapore, trading only with Malacca and Penang merchants.

In 1276 (A.H.) less rice began to come from Java, because the land formerly occupied by paddy was now planted by the Dutch with sugar-cane, owing to the fact, so said the Javanese who came hither, that sugar was far more profitable than paddy. A year or two afterwards the supply of rice from Acheen also began to diminish. The reason of this was that the men of Acheen planted black pepper, which they sold at a high price, though the cultivation of paddy was light work compared with that of pepper and sugar. Moreover in Malacca, where formerly there had been numerous paddy planters, the Chinese merchants roused themselves, opened up gardens, and grew potatoes and sago. Coolies were required for the work and good wages were offered. Thus it came to pass that many Malay planters, attracted by the high wages, became labourers for the merchants in their gardens. This practically ruined the cultivation, and from that time Malacca, Java and Acheen altogether lost their reputation for growing rice. Thereafter only a small quantity was produced.

In the year 1276 (A.H.) rinderpest broke out. One district in Selangor, i.e. Sungei Lukut, was then putting out a large quantity of tin, and Selangor men came and traded in Lukut, getting $3 and $4 for goods usually sold at $1. The natural result was that the art of paddy planting was almost forgotten. My people made large gain at Lukut, and also opened up Sungei Klang and Kuala Lumpur, tin mining being conducted at a profit in 1279 (A.H.). These were the two places in Selangor where tin mining existed in 1281 (A.H.). My grand-parents died at Lukut, leaving my father there.”

(Sumber: Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 25 November 1902, Page 3: |"Rice Cultivation").

LATAR PERISTIWA: Raja Berayun: 1857-1859: Peranan Dalam Perebutan Takhta

1859: Lawatan Raja Mahmud

Menurut Abdullah Hukum, antara tokoh awal sekitar Kuala Lumpur: “Tersebut kisah Raja Layang orang Minangkabau yang lari itu rupanya sampai di Sungai Ujong mendapatkan Tuan Syeikh Muhammad Taib, Tuan Syeikh Muhammad Ali dan Haji Muhammad Salleh Penghulu Rawang dahulu. Dia dapat ikhtiar di sana sehingga banyak pula pengikutnya. Dia pun berangkat dengan beratus-ratus orang rakyatnya sampai di sebelah hilir Kajang lalu membuat kubu di situ hendak melanggar Kajang. Perkhabaran itu kedengaran kepada Raja Berayun lalu diberinya tahu Raja Mahmud di Kuala Lumpur. Mendengar perkhabaran itu Raja Mahmud pun berangkat ke Kajang dengan segala pahlawannya dan saya pun sama mengiring. Tetapi Raja Layang telah lari malam apabila mendengar yang Raja Mahmud telah sampai di Kajang. Raja Mahmud sangat murka kepada Raja Layang. Ada khabar mengatakan Raja Layang lari ke Rekoh dan meskipun banyak orang memberi nasihat jangan turut Raja Layang tetapi Raja Mahmud berkeas jua katanya ada saudaranya di Rekoh. Pendeknya Raja Mahmud akhirnya tiba di Rekoh. Kata Tuan Haji Abdullah Hukm - di Rekoh dia melihat peri ganasnya tangan Raja Mahmud - Raja Mahmud bertemu dengan seorang Minangkabau yang nampaknya tiada ambil endah kepadanya. Ditanya oleh Raja Mahmud seperti berikut:-

Raja Mahmud: awak orang mana?

Jawabnya: saya orang Minangkabau!

Raja Mahmud: siapa ketuaan awak?

Jawabnya: Raja Layang!

Itulah dua patah soal jawab sahaja orang itu pun ditikam oleh Raja Mahmud sama sekali sahaja mati di situ jua. Raja Mahmud terus ke pekan Rekoh. Dia pun bertanya kepada seorang Kerinchi bernama Haji Muhammad Salleh di mana Haji Abdul Samad orang Minangkabau. Setelah diketahuinya daripada orang Kerinchi ini di mana Haji Abdul Samad maka Raja Mahmud pun pergi mendapatkan Haji Abdul Samad. Apabila bertemu lalu ditanya pula seperti berikut:

Raja Mahmud: siapa ketuaan Pak Haji?

Jawabnya: Tuankulah!

Mendengar itu Haji Abdul Samad pun dipeluk oleh Raja Mahmud dengan sukacitanya kerana niatnya hendak membunuh Pak Haji itu jika dia mengatakan berketuaan kepada Raja Layang. Di situlah Raja Mahmud mengeluarkan wang sepuluh ringgit belanja menanam orang yang ditikamnya tadi. Kemudian daripada itu maka Raja Mahmud pun berangkat balik ke Kuala Lumpur.”

(Sumber: Abdullah Hukum @ Warta Ahad, 1935; Adnan Haji Nawang, 1997: |"Kuala Lumpur Dari Perspektif Haji Abdullah Hukum: Bab 1: Riwayat Kuala Lumpur 24 Tahun Sebelum Pernaungan British", m.s.26-29).

1867-1875: Pelarian Perang Klang

Salah satu riwayat asal-usul nama “Kajang”, adalah berlatarkan kelompok-kelompok pelarian Perang Klang (1867-1873) di situ: “Perkataan Kajang lahir daripada beberapa sumber berikut : … Pendapat Ketiga : Menurut satu riwayat, maksud perkataan 'berkajang' bagi orang Mendailing berpondok. Manakala bagi orang Bugis 'bertikam atau bergaduh'. Kedua-dua puak ini pernah bertikaman di salah sebuah kawasan bukit berhadapan stesen keretapi yang ada sekarang, kerana salah faham maksud perkataan 'berkajang'. Peristiwa ini berlaku semasa kedua-dua golongan ini menghulu Sg. Langat kerana melarikan diri dari perang saudara yang berlaku di Kelang di antara tahun 1867 hingga 1873. Setelah peristiwa tersebut, tempat ini diberi nama Kajang” (Majlis Perbandaran Kajang, 2013: |"Asal-Usul Nama Kajang").

1876: Riwayat Abdullah Hukum (1935)

Abdullah Hukum pula ada menceritakan mengenai suatu peristiwa di Rekoh dan Bangi sekitar penghujung Perang Klang (1873-1875):-

“Abdullah Hukum dalam catatan memoirnya di akhbar Warta Ahad 1935 menyatakan beliau pernah membina benteng di Bangi bagi menuntut bela kepada Datuk Penggara dari Kuala Langat yang telah melarikan gundik Raja Mahmud semasa beliau masih menjadi juak - juak kepada Raja Mahmud (Penguasa Semenyih).

Beliau juga menulis peristiwa yang berlaku di rumah Raja Mahmud yang terletak di Bangi menerima rombongan kaum Kerinchi Sungai Ujong yang datang untuk menuntut diat kepada Raja Mahmud atas satu pembunuhan seorang penambang timah berketurunan Kerinchi dalam satu pergaduhan dan juga mengenai rancangan sulit Raja Mahmud dan rombongan Kerinchi tersebut untuk menyerang orang Bugis di Rekoh.

Catatan peristiwa ini pada dugaan saya kemungkinan berlaku sekitar tahun 1875 - 76 dalam umurnya sekitar 40 tahun setelah beliau keluar daripada persembunyiannya selama beberapa bulan di Kanching dan Mantin selepas tamatnya Perang Saudara di Selangor pada tahun 1874.

Abdullah Hukum kemudiannya mula belajar berniaga dan berdagang kain di Semenyih dan membuka sawah di Hulu Langat sebelum menetap di Kuala Lumpur dan akhirnya berjaya muncul sebagai salah seorang usahawan dan tokoh Melayu terkemuka di Kuala Lumpur pada era tersebut.

* Catatan memoir Abdullah Hukum berkaitan Bangi ini menjadi salah satu catatan terawal berkaitan Bangi oleh penduduk tempatan (Selangor) iaitu pada tahun 1935 yang dimuatkan secara bersiri dalam akhbar Warta Ahad diterbitkan di Singapura. Dicatatkan juga dalam memoirnya itu bahawa beliau merantau dari Kerinchi Sumatera semasa usianya 15 tahun pada tahun 1850 dan beliau meninggal dunia pada 1943 dalam usianya 108 tahun.”

(Sumber: Faizal Zainal @ Facebook Pekan Bangi, 24 Jun 2025: "Catatan Sejarah Bangi. Abdullah Hukum Di Bangi - 1876").

Petikan Sumber Asal

“Kuala Lumpur Alah

Suatu mesyuarat telah diadakan pada malam itu kerana mencari fikiran dan semua halnya telah ditampi teras dan didapati kebimbangan kerana kekuatan musuh. Keputusan mesyuarat ialah “undur”. Pada keesokan harinya beras dan makanan-makanan lain yang dibahagi-bahagi lalu lari mula-mulanya ke sebelah Pudu. Keadaan lari itu didahulukan perempuan manakala laki-laki berjalan di belakang menjaga dan melawan musuh kerana musuh sudah tentu akan menghambat. Dari Pudu terus ke Hulu Kelang ikut jalan dalam hutan jua. Musuh memburu dari belakang lari pula ke Hulu Gombak dan ke Hulu Batu akhirnya tembus ke Batu (tentang Rumah Pasung dahulu sekarang Checking Station). Dari situ lari pula ke Parit Tengah Bukit Kanching dari situ Tengku Mahmud dan sekalian orang Mendahiling terus lari ke Kuala Kubu. Tengku Panglima Raja ayahanda Tengku Mahmud masa itu tinggal di Cheras berkubu dan menjaga musuh sahaja bersama-sama dengan Raja Berayun dan Raja Mampang. Tengku Laut ibn Sultan Muhammad lari ke Kuala Lubu jua manakala waris-waris Kelang lari bertabur-tabur setengahnya ke Cheras, setengahnya ke Beranang dan sebahagian lain lari ke Kuala Semenyih. Kata sahibulhikayat - Tuan Haji Abdullah Hukum - saya dengan empat orang kawan tak kuasa hendak lari lagi lalu bersembunyi dalam hutan Kanching beberapa lama sehingga sudah senyap sedikit maka kami pun keluar lari ke Mantin. Duduklah saya di Mantin itu berdiam diri sahaja ada kira-kira enam bulan lamanya. Kemudian dapat khabar Raja Mahmud berserta dengan Raja Manan tiba pula di Kepayang (suatu tempat di antara Batang Labu dan Seremban). Kira-kira tiga bulan di belakang orang pun datang mendapatkan Raja Mahmud memberitahu yang seorang daripada gundiknya telah dilarikan oleh seorang Bugis namanya Datuk Penggara dan datangnya dari Kuala Langat. Sebab itu Raja Mahmud dengan kawan-kawannya balik bersiap dan menegakkan benteng di Bangi dengan maksud hendak menuntut bela jua. Adapun Sungai Langat itu lalu di Bangi dan dengan jalan sungai itu boleh hilir ke Kuala Langat ke mana gundiknya telah dilarikan orang itu tetapi sebelum dia dapat menuntut bela tumbuh pula berbagai-bagai halangan. Pada masa itu, timah tak boleh turun ke Kuala Langat sebab khabarnya kapal perang Inggeris ada di sana oleh sebab itu perniagaan timah itu dibawa ikut jalan ke Seremban diupah menggalasnya.

Kerinchi Menuntut Bela

Adapun orang yang mengambil upah menggalas timah dan beras di antara Seremban itu kebanyakkannya orang Kerinchi. Cina ada dua tiga orang sahaja. Pada suatu hari satu kumpulan orang Kerinchi menggalas timah telah disamun orang. Oleh kerana orang Kerinchi itu melawan maka suatu perkelahian telah berbangkit. Sungguhpun barang-barang itu tak dapat dirampas oleh penyamun itu, tetapi dengan malangnya seorang Kerinchi telah terbunuh dalam perkelahian itu. Kemudian disiasat didapati bahawa kepala penyamun itu ialah Panglima Muda Sepajar orang Batu Bara, iaitu orang Raja Mahmud. Lapan hari di belakang perkhabaran itu sampailah kepada orang Kerinchi Sungai Ujong (Seremban) oleh itu orang Kerinchi pun mengadakan suatu mesyuarat kerana hendak menuntut diat kepada Raja Mahmud itu. Apabila Engku Tua telah memberi izin maka orang Kerinchi itu pun berjalan ada kira-kira 30 orang banyaknya di antaranya ialah Imam Perang Alam, Haji Arshad, Haji Mansur, Haji Abdul Latif, Haji Muhammad Shah dan (sahibulhikayat) Haji Abdullah Hukum. Apabila sampai di Bangi orang Kerinchi itu telah diterima baik oleh Raja Mahmud, dipersilakannya ke dalam, dipersilakan duduk dan disorongkannya tepak sirih serta dia bertanya apa hajat? Apabila sirih telah dikapur maka Imam Perang Mangku, iaitu kepala dan jurukata orang Kerinchi itu pun berkata, “Harap diampun Tengku! Kedatangan patik semua ini ialah kerana hendak mengadu seorang daripada waris kami telah mati dalam kawasan Tengku. Itulah kami sembahkan jika hilang minta dicari, cicir minta dipungut, kalau luke minta dipampas dan jika mati minta didiat.” Ada sejurus lamanya maka Raja Mahmud pun tidak berpanjang madah lagi melainkan mengaku akan membayar diatnya. Ketika itu jua dia bertitah kepada adindanya Raja Manan suruh berikan sarung keris terapang emas akan jadi tanda diat itu dengan sabdanya apabila dia sampai di Sungai Ujong dia akan menebus tanda itu $100. Tanda itu pun diterima oleh Imam Perang Mangku seraya berdiri minta diri tetapi Raja Mahmud bertitah pula suruh kami duduk sebentar lagi. Kami pun duduk dan Raja Mahmud bertanyakan perihal orang Bugis yang di Rekoh itu. Katanya dia hendak menghalau mereka dari situ. Kata Imam Perang Mangku adapun Bugis di Rekoh itu sedang berkira hendak melanggar. Akhirnya Raja Mahmud mengajak kami berpadan supaya apabila Bugis datang melanggar orang Kerinchi belot. Setelah kami semua mengaku setia maka kami pun balik terus menghadap Engku Tua mangatakan yang Raja Mahmud mengaku akan membayar diat.

Bugis Rekoh Alah

Kebetulan Bugis di Rekoh pada masa itu sedang bersiap hendak melanggar Raja Mahmud. Kawannya ialah orang Tembusi, orang Kampar dan juga orang Kerinchi. Rahsia di antara orang Kerinchi dengan Raja Mahmud itu disimpan baik-baik sehingga seorang pun tiada tahu. Pada keesokannya kira-kira pukul tujuh pagi sampailah sekalian pada suatu tempat berhadapan dengan kubu Raja Mahmud. Masing-masing pihak membuat kubu. Orang Kerinchi sebuah, Bugis sebuah, Tembusi dan Kampar sebuah-sebuah pula. Orang Kerinchi mendirikan kubu di sebelah matahari hidup kerana menurut persetiaan dengan Raja Mahmud dan tembak orang Kerinchi tiada berpeluru. Sejurus lamanya maka orang Kerinchi pun menembak kubu Raja Mahmud tetapi tiada peluru. Oleh itu Raja Mahmud pun faham akan isyarat-isyarat itu dan dia pun keluar dengan serta-merta menyerang orang yang di sebelah matahari mati sahaja. Ketika itu kebetulan orang Bugis dengan sekalian orang Kampar dan Tembusi itu belum siap. Apa lagi boleh dikata apa kata Raja Mahmud saja. Panglima-panglima orang Bugis telah mati enam orang, banyak yang luka-luka manakala di sebelah Raja Mahmud seorang pun tiada mati. Sebentar lagi orang Bugis dan kawan-kawannya pun tewas lalu lari ke dalam hutan bertabur-tabur dan setengah-setengahnya lari masuk perahu. Kata Tuan Haji Abdullah Hukum inilah penghabisan pergaduhan di sebelah darat Selangor. Apabila Bugis telah lari maka negeri pun aman.”

(Sumber: Adnan Haji Nawang, 1997: "Kuala Lumpur dari Perspektif Haji Abdullah Hukum", m.s.32-37).

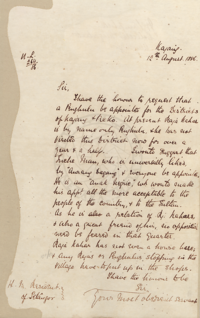

1875: Lawatan Frank Swettenham

Latar peristiwa: Setelah tamatnya Perang Klang di Selangor, Frank Swettenham yang telah banyak memainkan peranan dalam campurtangan British di negeri itu telah dilantik sebagai penasihat Sultan Selangor pada Ogos 1874, kemudiannya Pembantu Residen Selangor pada Disember 1874: “On 4 January 1871 a battered paddle-steamer, the S. S. Pluto , limped into Singapore harbour. Destined for the use of the Straits Governor, it carried on board two Cadets of the Straits civil service, one of whom was Frank Swettenham. Some six months later, in July 1871, another British ship, the H.M.S. Rinaldo , was wreaking vengeance on Malay 'pirates' by bombarding the fort at Kuala Selangor . The connection between these events was not then apparent, and even now may seem to be a cunning historian's device: the Selangor 'incident' turned out to be the prelude of further British involvement in that state, and of the Intervention of 1874 Swettenham was a leading agent. In August 1874 he was sent as an informal adviser to the Sultan, at the end of that year he was appointed Assistant Resident at Langat, and from 1882 to 1889 he served as fully fledged Resident of Selangor. … Between August 1874 and October 1875 (when Davidson and Swettenham were given temporary appointments in Perak to implement Governor Jervois' policy of direct control) the British officers were generally an asset to the established Selangor authori- ties. Swettenham brought about a reconciliation between Sultan Abdul-Samad and his son-in-law, Kudin; persuaded Mahdi's lieutenant, Raja Mahmud, to 'surrender' and remain at Singapore; audited and systematised Kudin's accounts at Klang; mediated in a dispute between Kudin and Bendahara Wan Ahmad of Pahang with fair success; and otherwise kept out of the way of the Malay rulers by travelling extensively in the state.” (Ernest Chew @ Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society Vol. 57, No. 1 (246) (1984): |"FRANK SWETTENHAM AND YAP AH LOY: THE INCREASE OF BRITISH POLITICAL 'INFLUENCE' IN KUALA LUMPUR, 1871-1885", m.s.70-73).

Lukisan gambaran serangan H.M.S.Rinaldo terhadap Kuala Selangor pada tahun 1871 (Stefan Eklöf Amirell, 2018: |"Civilizing pirates: Nineteenth century British ideas about piracy, race and civilization in the Malay Archipelago", m.s.36): “HMS Rinaldo bombarding Salangore, in the Strait of Malacca (engraving); 1625891 HMS Rinaldo bombarding Salangore, in the Strait of Malacca (engraving) by English School, (19th century); Private Collection; (add.info.: HMS Rinaldo bombarding Salangore, in the Strait of Malacca. Illustration for The Illustrated London News, 2 September 1871. English School (19th Century)); Look and Learn / Illustrated Papers Collection. © Look and Learn / Illustrated Papers Collection / Bridgeman Images … This engraving showcases the dramatic scene of HMS Rinaldo bombarding Salangore in the Strait of Malacca. Created by an English School artist in the 19th century, this print captures a significant moment in maritime history. The image depicts the intense naval combat between HMS Rinaldo, a vessel from the Royal Navy, and Salangore, a strategic location in Malaysia. The powerful bombardment is evident as explosions fill the air and waves crash against both ships. This historical event was documented for The Illustrated London News on September 2nd, 1871. The artwork not only highlights the military prowess of HMS Rinaldo but also emphasizes the importance of this region for trade and exploration during that time.” (Media Storehouse: |"HMS Rinaldo bombarding Salangore, in the Strait of Malacca (engraving)").

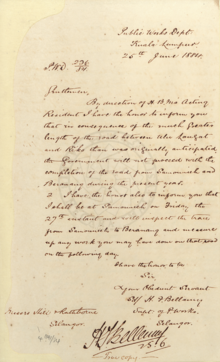

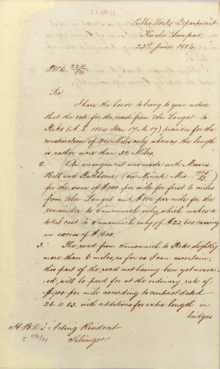

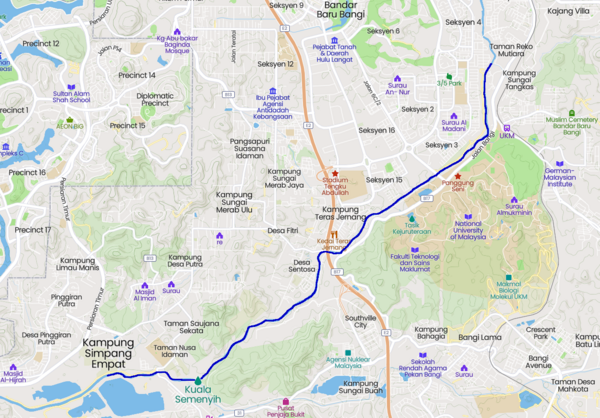

Pada tahun 1875, Frank Swettenham telah menjelajah sepanjang Sungai Langat, dan merupakan pembesar British yang pertama tiba di Rekoh. Perjalanan beliau dari Bandar Langat (Kuala Langat) ke Rekoh sejauh 57 batu mengambil masa kira-kira 5 hari. Ketika itu Sungai Langat merupakan satu-satunya jalan pengangkutan hasil bijih timah dari kawasan pedalaman. Pada musim kering, perjalanan tersebut mengambil masa 13 hari, akibat aras air sungai yang cetek. Percubaan awal pembuatan jalan dari Rekoh ke Klang telah ditangguhkan, oleh kerana kawasan hutan paya yang luas di antaranya: “Until 1883, when it became a separate administrative district with Kajang as its headquarters, Ulu Langat was merely an inland extension of Kuala Langat. Anderson, for example, in 1824 described the Langat as 'a small river' with about 500 people along its valley, who exported tin and rattan. He did not himself venture so far south in Selangor as this. If he had done so, he would have found that the winding river was navigable to small ships and also tidal to a point some 12 miles upstream from Bandar Langat, with a minimum depth of 12 feet. From that point, the character of the river changed, so that in 1875 it took Swettenham five days to cover a distance of 57 miles from Bandar Langat to Rekoh. He found the river 'very difficult, the current always getting stronger, and the snags were numerous and larger'. From Kajang he struggled on to Cheras and finally to Ulu Langat village, a total distance of 93 miles from Bandar Langat.3 He proposed to bypass the middle stretch with a road, but the land was swampy and so the road was not constructed until the early twentieth century, when the advent of rubber had created both a need and the resources for it. Nonetheless, until lateral roads to link Ulu Langat with Kuala Lumpur and Seremban were built in the 1880s, the river was the only means of exporting tin, and in the dry season the water level dropped so that a heavily laden boat might take 13 days to travel downstream.” (J. M. Gullick @ JMBRAS Vol. 80, No. 2 (293) (December 2007): |"A Short History of Ulu Langat to 1900", m.s.1).

Sekitar waktu ini (1875), balai polis Kajang dibina sebagai usaha mengembalikan keamanan selepas peperangan tersebut: “Situated nearby, across Jalan Cheras, is the Police Station, which was established in 1875, after the British succeeded in crushing Sutan Puasa’s suspected uprising. Across Jalan Hishammudin is the Post Office, which was also built at about the same time as the former Ulu Langat District Office; it is still in operation until today.” (Eric Lim @ Museum Volunteers, JMM, July 15, 2020: |"History of Kajang"). Kemungkinan balai polis Rekoh juga dibina sekitar waktu yang sama.

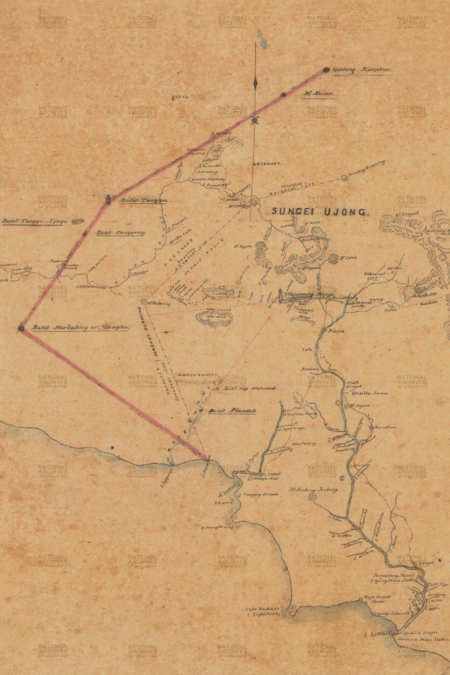

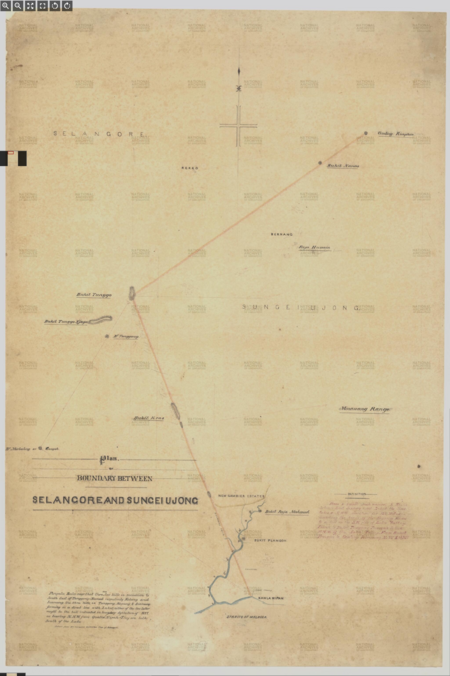

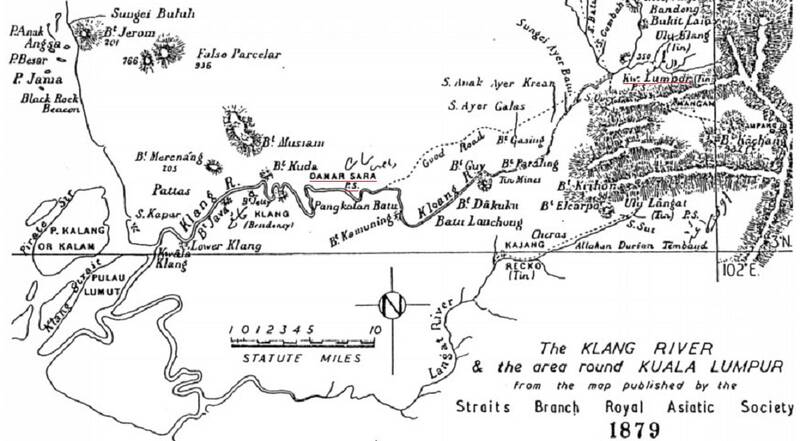

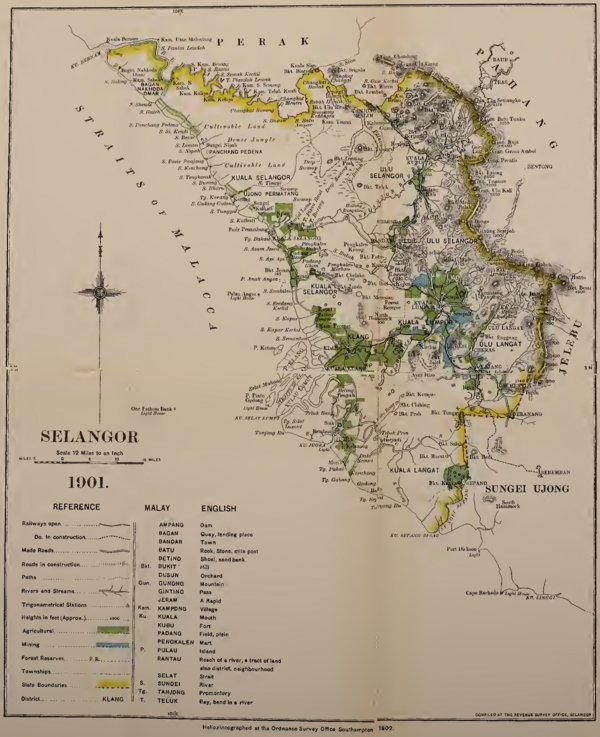

Peta sempadan Selangor-Sungai Ujong, 1876. Ketika itu Rekoh (Recko) masih di bawah pengaruh Sungei Ujong, manakala Lukut di bawah Selangor. Frank Swettenham memudiki Sungai Langat dari Bandar Langat ke Rekoh (ada di dalam peta ini), seterusnya ke Kajang, Cheras, dan Ulu Langat (tiada di dalam peta ini - hanya setakat Sungai Kajang dan Sungai Jebat sahaja): “compiled from sketch surveys made by Captain Innes R E, J W Birch and D Daly, and Admiralty Charts. Lithographed under the direction of Lt. Col. R. Home C.B.R.E” (Royal Geographical Society, London; Royal Geographical Society (Great Britain), 1876: |"Map of Part of The Malay Peninsula, 1876").

Perjalanan dari Bandar Termasa (Langat) ke Rekoh telah dijadikan contoh ayat di dalam kamus istilah karya beliau:-

| How far is it by river from Bandar Termasa [Langat] to Rekoh? | Brapa jauh deri-pada Bandar Termasa mudik ka'Rekoh?” |

| We can reach it with one day's rowing and six day's poling. | Satu hari ber-daiung anam hari ber-galah, bulih sampei. |

(Sumber: Frank Swettenham, 1910: |"Vocabulary of the English and Malay languages with notes", m.s.220).

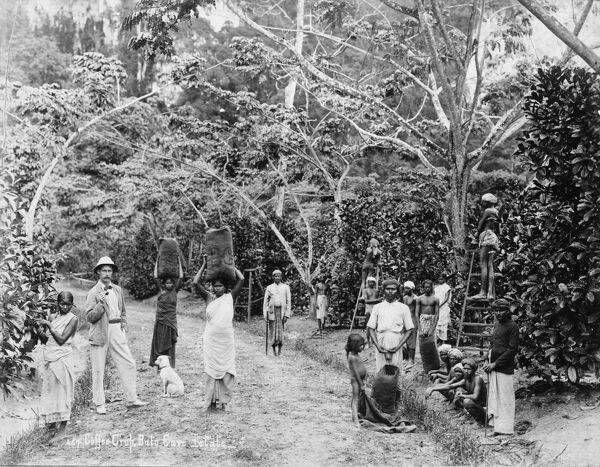

“Mengikut laporan Swettenham yang membuat lawatan ke tempat itu pada tahun 1875, pada masa itu Rekoh mempunyai penduduk tidak lebih daripada seratus orang yang terdiri daripada orang Melayu, Bugis, Cina dan Korinci. Mereka berada di bawah seorang ketua kampung Bugis (orang Bugis) yang dilantik oleh pembesar Sungai Ujong. Bagaimanapun, ketua kampung itu mungkin tidak disukai oleh penduduk tempat itu. Dia kemudian berpindah ke Singapura. Mengikut laporan Swettenham seterusnya, ” The village 'had the appearance of having been once a very prosperous place. There are plenty of substantial shops and houses built of plank and mud, as good native houses as I have seen anywhere, the Sungai Ujong style but better than houses there…a first Bazaar for houses that ia badly off for water.'“ (Andin Salleh, July 18, 2013: |"Pekan Rekoh yang sudah lenyap"). Dari sumber lain: “In March 1875 Rekoh had a population of no more than a hundred, Malays, Bugis, Chinese and Korinchi, under a Bugis head-man appointed by the ruling chief of Sungei Ujong. The headman evidently found this an unwelcome responsibility and had taken himself off to Singapore. The village 'had the appearance of having once been a very prosperous place. There are plenty of most substantial shops and houses built of plank and mud, as good native houses as I have seen anywhere, the Sungei Ujong style but better than the houses there…a first rate Bazaar for houses that is badly off for wares.'” (J.M. Gullick, 1998: "A History of Selangor 1766-1939", m.s. 74). Terjemahan: “Pada bulan Mac 1875, Rekoh mempunyai penduduk tidak lebih daripada seratus orang, terdiri daripada orang Melayu, Bugis, Cina dan Kerinchi, yang dipimpin oleh seorang ketua berdarah Bugis yang dilantik oleh pemerintah Sungei Ujong. Ketua berkenaan enggan menggalas tanggungjawab yang diberikan, lalu lari ke Singapura. Kampung itu “kelihatan seperti sebuah tempat yang amat makmur suatu masa dulu. Ada banyak kedai dan rumah besar yang dibina daripada papan dan lumpur, sama bagusnya dengan rumah-rumah peribumi yang pernah saya lihat di tempat lain, dengan gaya Sungei Ujong tetapi lebih bagus daripada rumah-rumah di sana… pasar kelas pertama untuk rumah-rumah yang jauh dari sumber.” (terjemahan Ashraf Khalid & Akmal Khuzairy Abd Rahman @ IBDE, 2022: "Sejarah Selangor 1766–1939 - J.M. Gullick", m.s.111).

LATAR PERISTIWA: Jalan Rekoh-Telok Datok

1875-1882: Pentadbiran Raja Kahar

Sekitar tahun 1875, Sultan Selangor, Sultan Abdul Samad telah melantik salah seorang puteranya, Raja Kahar, sebagai pentadbir (Malay Magistrate) daerah Ulu Langat, termasuk Kajang dan Rekoh. Antara faktor keputusan ini ialah kehendak baginda untuk mengembalikan pengaruh keluarganya di daerah tersebut, yang ketika itu di bawah pengaruh Sungei Ujong: “Until 1880 it was the policy of the colonial regime, dictated by the need to practise strict economy, to leave the interior of Selangor in the charge of local notables, and the Sultan wished that his sons would perform public duties in consideration of receiving 'political allowances' from the state treasury. Thus it was that Raja Kahar had charge of the Ulu Langat district as 'Malay Magistrate' for some years. There were particular factors conducive to this arrangement. The Sultan regarded Ulu Langat as his patrimony, inherited from his father, Raja Abdullah, and he was anxious to restore his authority over the part that had fallen under the control of Sungei Ujong. The Sultan's investment in mining through advances to Chinese working in Ulu Langat, which had begun in the 1860s, continued. Employing Kahar to supervise his interests was an example of his general practice of using kindred as proxies. He had sent one of his wives to live in a paddy area opened with his aid. Raja Kahar first appears in the extant records in February 1874, when Sir Andrew Clarke visited Bandar Langat; he and his advisers then first made contact with the Selangor royal family.” (J. M. Gullick @ Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society Vol. 80, No. 2 (293) (December 2007): |"A Short History of Ulu Langat to 1900", m.s. 7-8).

![Tunku Abdul Kahar [Tahir] Tunku Abdul Kahar [Tahir]](/_media/gambar/wangsa-mahkota-selangor-royal-selangor-ku-alam-1.jpg?w=280&tok=50e26f)

Raja Kahar, Raja yang menjaga Kajang (Wangsa Mahkota Selangor, 19 Jan 2014: |"Y.A.M. Tunku Abdul Kahar [Tahir] ibni Almarhum Sultan Sir ‘Abdu’l Samad Shah").

Tindakan ini telah mengakibatkan ketegangan di antara Selangor dan Sungai Ujong, oleh kerana sebelum ini keduanya bersempadankan Sungai Langat: “Kawasan Sungai Ujong masa dahulu sangat luas, beberapa buah tempat di dalam Negeri Selangor sekarang ini dahulunya dalam kawasan Sungai Ujong. Tempat itu ialah seperti Kajang, Rakoh, Semenyeh, Beranang dan beberapa kampong lain lagi yang kecil-kecil. Sempadan di antara Dato' Kelana Sungai Ujong dengan To' Engku Kelang, Batang Langat (Sungai Langat). Kanan mudek kawasan Sungai Ojong dan kiri mudek kawasan Dato' Engku Kelang. Kawasan sebelah kanan Sungai Langat ini ialah kawasan-kawasan yang termasuk Kajang, Semenyeh, Rakoh dan Beranang. Pada masa Sungai Ujong di perintah oleh Dato' Kelana Sendeng (Dato' Kelana ke-V) Semenyeh telah diberikan kepada Tunku Sutan menantu kepada Raja Husin waris Sungai Ujong. Tunku Sutan dan Raja Husin telah membuka Semenyeh hingga ramai penduduk-penduduknya. Banyak hasil bijih timah dikeluarkan dari sana dan telah diberi izin oleh Dato' Kelana akan Tunku Sutan dan Raja Husin memungut cukai-cukai itu untuk sara hidup mereka. Kemudian Raja Husin membuka Beranang pula pada tahun 1878. Kemudian Tengku Kahar Putera Sultan A. Samad duduk di Kajang hingga Inggeris mencampuri pemerintahan Negeri Selangor.” (Perpustakaan Negeri Sembilan: |"Sungai Ujong").

Sempadan asal Kelang-Sungai Ujong menurut Terombo Sungai Ujong (1901): “FASAL 11. Sempadan Sungai Ujong Dengan Dato'-dato' Yang Empat, Kelang, Sg. Ujong, Jelebu dan Johol. 11.1. Kawasannya yang telah dibuka oleh Batin-Batin dibawah pemerentah masing-masing iaitu Batang Langat, Kuala Labu, Bukit Jukerah, Lalu ke Tunggul Sejaga, Semonyeh terus ke Merbok Awang Hilir Rakoh, Subang Hilang, antara Kajang dan Rakoh terus ke Bukit Perhentian Rimbun perbatasan dengan Pahang. 11.2. Sebelah kiri mudik Sungai Langat di punyai oleh Kelang. Sebelah Kanan mudik Sungai Langat Sungai Ujong punya.” (Susunan Haji Muhammmad Tainu dan Zaini bt. Abd. Hamid, Jawatan Kuasa Penyelidikan Budaya Negeri Sembilan, November 1993, berdasarkan Raja Aman Raja Hussin, 1901: Terombo Sungai Ujong: |"Rengkasan Terombo Sungai Ujong", m.s.9-10).

Terdapat perkhabaran bahawa Raja Kahar turut tidak disenangi sesetengah pihak di perkampungan Ulu Langat, namun Swettenham berpendapat sebaliknya, lalu menyokong beliau: ”(Swettenham to Sec. for Native States, 8 Apr. 1875, enclosed in Clarke to Sec. State, 27 Apr. 1875, CO 809/5): There were also increasing complaints about Raja Kahar. Soon after Swettenham had arrived in Langat, 'Abdul-Samad permitted him to take charge of the Ulu Langat district. In early 1873 complaints were frequently made by people in the village of Ulu Langat about the raja’s behaviour and when Swettenham visited the district later the same month he went armed with a letter from the Sultan instructing his son to obey Swettenham. Contrary to his expectations he was very impressed by Kahar's efforts to restore the town of Kajang and revive its trade and encourage reopening of mines in the area. The source of the complaints was a Menangkabau Imam, Prang Mat Asis, who collected duties in Ulu Langat and resented Raja Kahar's presence. Swettenham claimed that from this episode the word spread that there was wide-spread discontent and migration from Ulu Langat; but in his opinion there was no evidence either at Kajang or Ulu Langat village that Raja Kahar had abused his powers. Instead, at both places Swettenham supported the authority of the Raja and confirmed his right to collect taxes. He permitted the Imam to collect duties at Ulu Langat on the condition that they were sent to Tungku Zia'u'd-din (25 March 1875: Swettenham hoped eventually to have penghulu's established at Reko, Kajang, Cheras and Ulu Langat, each collecting a two dollar duty on every bhara of tin , half going to the Sultan and the remainder to the penghulu). By August, however, Swettenham was informed that Raja Kahar was acting arbitrarily; he had on one occasion taken a daughter from one man who owed him money and on another he had confiscated a quantity of tin. The latter story especially, it was said, had frightened off investors and traders to the district.” (P.L. Burns, November 1965: |"The Constitutional History of Malaya With Special Reference to the Malay States of Perak, Selangor, Negri and Pahang 1874-1914", m.s. 63-64).

Menurut Abdullah Hukum (sambungan penghabisan Perang Klang, sekitar 1875): “Apabila Bugis telah lari maka negeri pun aman. Saya pun duduk di Semenyih berniaga kain ada kira-kira dua tahun lamanya. Adapun Semenyih itu ialah di bawah perintah Raja Husin seorang raja peranakan Sungai Ujong. Hulu Langat, Kajang dan Rekoh masa itu di bawah perintah Raja Kahar Ibn Sultan Abdul Samad. Tengku itu jua majistretnya masa itu dan Tengku itu memberi hukum kepada orang Minangkabau seperti Panglima Muda, Khatib Raja, Ginti Ali dan jurutulis supaya memulangkan harta-harta orang Mendahiling yang dirampas dahulu dipulangkan kepada Raja Yusof dan Fatimah cucu daripada Datuk Penghulu Langat. Saya duduk pula membuka sawah di Langat ada kira-kira dua tahun. Dalam masa saya tinggal di Hulu Langat itu saya mula-mula dapat memandang wajah Yang Maha Mulia Tuanku Sultan Abdul Samad, iaitu pada masa Yang Maha Mulia itu berangkat kerana suatu lawatan melihat persawahan di sana dan Yang Maha Mulia sendiri ada mengaturkan sawah-sawah itu. Kedatangan Yang Maha Mulia itu dari Kuala Lumpur ialah dengan jalan sungai dan bertandu. Yang Maha Mulia itu diiringi oleh ramai dayang-dayang dan hulubalang. Kemudian saya berpindah pula ke Kuala Lumpur menuju rumah Raja Bot dan Raja Syam. Ketika itu saya ingat Raja Bot berkata yang perang telah berhenti kira-kira 30 tahun.” (Adnan Haji Nawang, 1997: "Kuala Lumpur dari Perspektif Haji Abdullah Hukum", m.s.37).

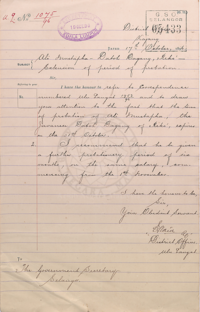

1878-02-10: Menjadi Sebahagian Negeri Selangor

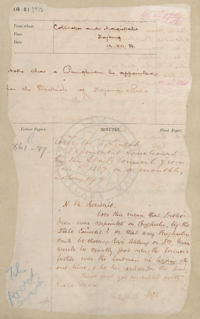

Di dalam suatu perjanjian yang ditandatangani pada 10 Februari 1878, antara lain, Rekoh telah diserahkan kepada Sultan Abdul Samad, lalu dengan rasminya menjadi sebahagian daripada negeri Selangor:-

“Pada hari ini dalam tahun 1878, satu perjanjian mengenai sempadan negeri Selangor dan Sungai Ujung dibuat di antara Sultan Abdul Samad, Yang di-Pertuan Negeri Selangor dengan Dato' Kelana Sungai Ujung, Tengku Saiyid Abdul Rahman. Perjanjian itu antara lain menyatakan bahawa:-

Pertama: Dengan nasihat Kapten Bloomfield Douglas (Residen British di Selangor) Sultan Abdul Samad, bagi pihak dirinya, dan puteranya Raja Musa atau sesiapa juga penggantinya yang akan ditabalkan sebagai Sultan dan waris-warisnya, mulai saat itu mengaku bahawa kawasan Lukut yang pada masa itu diperintah oleh Raja Bot dan semua kawasan tanah dalam Sungai Raya yang sekarang diperintah oleh Raja Daud, yang kesemuanya itu adalah di bawah kekuasaan Sultan Abdul Samad.

Kedua: Dengan nasihat Kapten Murray (Residen British di Sungai Ujung), Tengku Saiyid Abdul Rahman bagi pihak dirinya, pengganti-penggantinya dan waris-warisnya atau sesiapa juga yang memerintah Sungai Ujung dan bergelar Dato' Kelana, mengaku bahawa mulai dari saat itu kawasan yang terletak di Seberang Tebing Sungai Langat bernama Rekoh dan semua tanah bernama Labu adalah diserahkan kepada Sultan Abdul Samad Selangor, pengganti-penggantinya dan waris-warisnya untuk selama-lamanya.

Bagaimanapun, perjanjian itu telah dibantah oleh Raja Bot yang memerintah Lukut kerana beliau tidak diajak berunding mahupun diminta pendapatnya dalam rundingan mengenai perjanjian itu. Raja Bot membantah keras mengenai keputusan memasukkan Lukut dalam perintah Sungai Ujung kerana daerah itu adalah kepunyaan ayahandanya, Raja Jumaat, yang telah diberikan oleh Almarhum Sultan Muhammad pada tahun 1846.”

(Sumber: Hari Ini Dalam Sejarah @ Arkib Negara Malaysia, Ahad 10/02/1878: |"PERJANJIAN SEMPADAN SELANGOR - SUNGAI UJUNG").