Jadual Kandungan

Getah di Malaya

Dirujuk oleh

Cebisan Sejarah

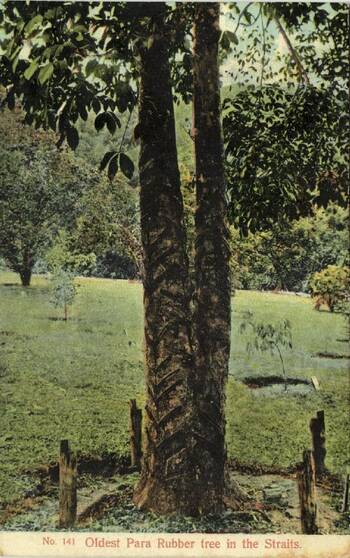

1896: Pokok Getah Tertua di Negeri-negeri Selat

Pokok getah tertua di Negeri-negeri Selat: “Straits settlements, malay malaysia, oldest para rubber tree (1910s). Condition: Very Good, unused ca. 1910, some album pressure marks” (A. Kaulfuss (1861-1909), Penang, BENDAV POSTCARDS @ HipPostcard: |"straits settlements, Malay Malaysia, Oldest Para Rubber Tree (1910s)").

Menurut sumber lain: “Description: rare early tinted / colored postcard depicting ” No. 141 Oldest Para Rubber Tree in the Straits“, a great view of a very old rubber tree” (k_braun @ WorthPoint: |"1910S PENANG OLDEST PARA RUBBER TREE STRAITS PC MALAYA").

Lokasinya mungkin di Taman Botani Pulau Pinang, dan ditanam sekitar tahun 1896: “Returning to Penang in 1892 fully recovered, he (Charles Curtis, botanist for Gardens and Forests Department of the Straits Settlements) embarked on a project to plant nutmeg, clove, durian, banana, betel nut and other interesting and famous Penang trees in a location to allow visitors to see everything within a short period of time and return well ahead of their scheduled steamer departure. Four years later, he began planting rubber trees at the Penang Botanic Gardens on the insistence of Henry Nicholas Ridley, director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens, who pioneered its development in Malaya and the region.” (ALAM TEAH LEAM SENG @ New Straits Times, September 30, 2019: |"How Penang Botanic Gardens took root").

Awal 1900-an: Getah di Ulu Langat

“Tin mining industry in the district turned out to be a relatively minor enterprise, paling in comparison to other towns in the state. This prompted the District Office to suggest moving to agriculture. Tobacco had been planted in 1890 on a trial basis in Semenyih but the project failed. Coffee was next and it gained interest amongst European planters who were applying for land for coffee planting. Chinese businessmen were equally interested and joined in the demand for land. However, at the turn of the 20th century, faced with strong competition from Brazilian coffee producers, fluctuation of coffee prices and the appearance of a fungal disease called H. vastatrix and further assisted by the outbreaks of Cephonodes hylas moth that threatened to cripple the local coffee production, the industry soon vanished from the scene.

Rubber was the next big crop. The Inch Kenneth Estate located just outside Kajang became the first estate to plant rubber on a commercial scale in Malaya. Among the Chinese planters who obtained land in Kajang for rubber plantation were Choo Kia Peng with 182ha in 1910, Loke Yew with 41ha in 1912 and Low Ti Kok with 24ha. Goh Ah Ngee, who had tin mines in Balau, also ventured into rubber plantation in Semenyih after his failed ventures in coffee planting. The development of the rubber industry was also helped by the extension of the railway track southwards from Kuala Lumpur to Kajang in 1897. Before that, Kajang was connected to Kuala Lumpur via a cart road built in 1888.”

“Inch Kenneth Estate sign near Kajang.”

(Sumber: Eric Lim @ Museum Volunteers, JMM, July 15, 2020: |"History of Kajang").

PERIHAL LANJUT: Inch Kenneth Estate (1894).

1906-04-20: Keadaan Getah di Malaya

| Tarikh | Butiran Keratan | |

|---|---|---|

| | 1906.04.20 | "MALAYA AND RUBBER". The Straits Times, 20 April 1906, Page 9 |

Pembukaan ladang-ladang getah di Malaya (Bukan di Bangi, tapi masih kawasan sekitarnya, dan menarik untuk dibaca).

LATAR PERISTIWA: Ladang Prang Besar: Rencana menarik berkenaan sejarah ladang Prang Besar berhampiran Bangi (kini Putrajaya): |"The Story of Prang Besar Estate", oleh VD Nair (Pengurus estet Prang Besar tahun 1950-an)

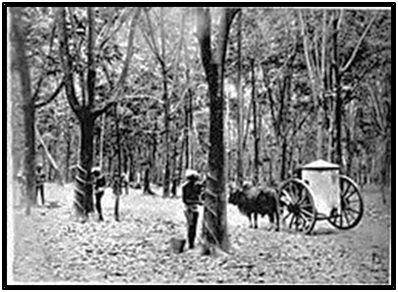

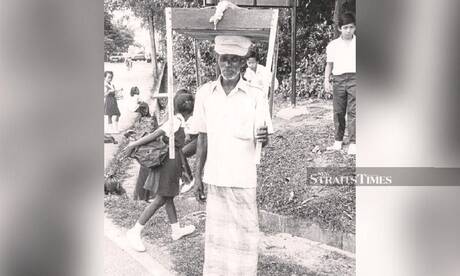

“Late in the morning, Indian rubber tappers would collect latex from the cups, pour it into the buckets and then the buckets would be emptied into the large collecting bin on the cart. In the early days the cart was towed by bullocks and the latex in the bin would be taken to the collecting centre to be processed into rubber sheets.” (VD Nair, |"The Story of Prang Besar Estate").

Sumber lain: |James Hagan, Andrew Wells, 2005: "The British and rubber in Malaya, c1890-1940"

1907: Koleksi Gambar Charles Kleingrothe

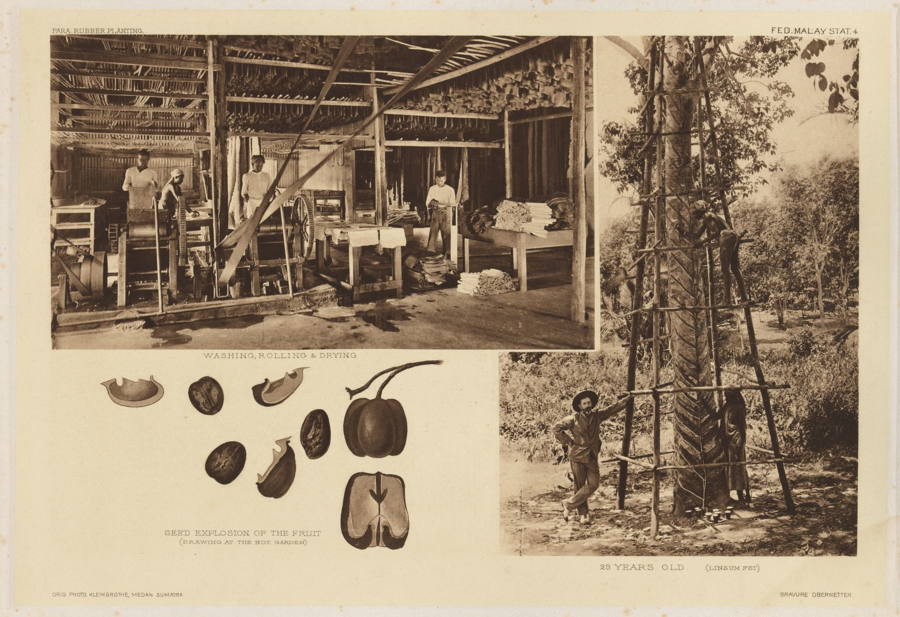

Kaedah pemprosesan getah ketika itu: “Fed. Malay Stat. 4: Washing, Rolling & Drying / Seed Explosion of the Fruit (Drawing at the Bot Garden) / 23 Years Old (Linsum Fst) 1907” (|Charles Kleingrothe, 1907: |"Fed. Malay Stat. 4: Washing, Rolling & Drying / Seed Explosion of the Fruit (Drawing at the Bot Garden) / 23 Years Old (Linsum Fst) 1907").

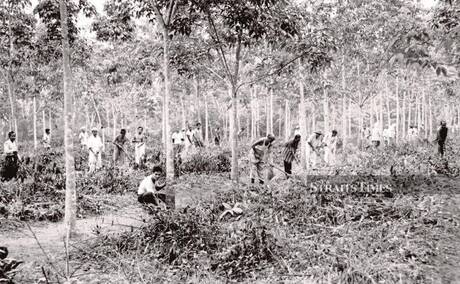

Pembukaan Ladang

![Para rubber planting. Clearing jungel [i.e jungle], 1907 Para rubber planting. Clearing jungel [i.e jungle], 1907](/_media/gambar/189779.jpg?w=600&tok=f9dfe5)

“Para rubber planting. Clearing jungel [i.e jungle], 1907. General view of estate with cleared land being burned.” (Cambridge University Library: |"Para rubber planting. Clearing jungel [i.e jungle], 1907". Gambar: |Charles Kleingrothe, 1907: |Fed. Malay Stat. 2: Clearing Jungle / Seed Planting / Nursery 1907).

Penanaman Getah

![Para robber[i.e. rubber] planting. Seed planting, 1907 Para robber[i.e. rubber] planting. Seed planting, 1907](/_media/gambar/189780.jpg?w=600&tok=31c4f4)

“Para robber[i.e. rubber] planting. Seed planting, 1907. Showing labourers raking earth and planting seeds.” (Cambridge University Library: |"Para robber[i.e. rubber] planting. Seed planting, 1907". Gambar: |Charles Kleingrothe, 1907: |Fed. Malay Stat. 2: Clearing Jungle / Seed Planting / Nursery 1907).

![Para rubber planting. Nurseri [i.e Nursery], 1907 Para rubber planting. Nurseri [i.e Nursery], 1907](/_media/gambar/189781.jpg?w=600&tok=929c05)

“Showing young plants in nursery beds.” (Cambridge University Library: |"Para rubber planting. Nurseri [i.e Nursery], 1907". Gambar: |Charles Kleingrothe, 1907: |Fed. Malay Stat. 2: Clearing Jungle / Seed Planting / Nursery 1907).

“Showing nursery beds, with older trees in the background.” (Cambridge University Library: |"Para rubber planting. Nursery and 6 year old plantation, 1907". Gambar: |Charles Kleingrothe, 1907: |"Para rubber planting. Nursery and 6 year old plantation, 1907").

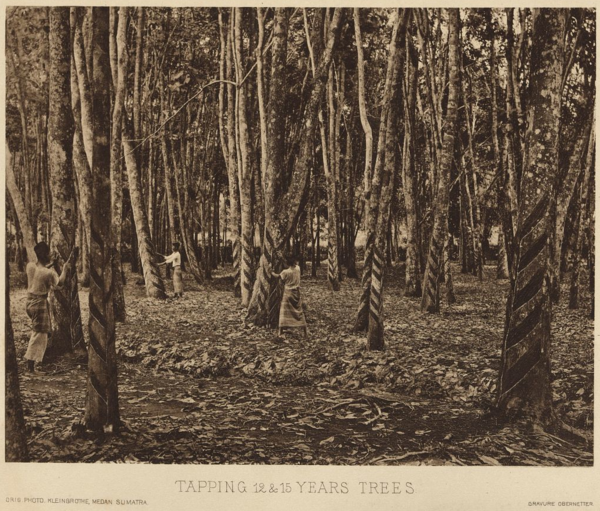

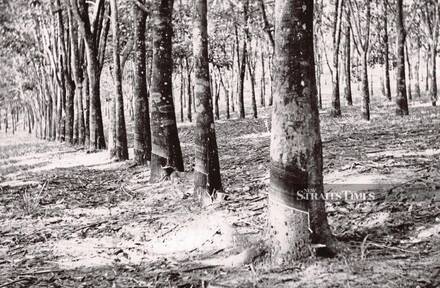

Penorehan Getah

Penorehan pokok getah berumur 12 dan 15 tahun: “Taping 12 and 15 year old trees, 1907. Showing estate workers making incisions in mature trees for tapping.” (Cambridge University Library: |"Taping 12 and 15 year old trees, 1907". Gambar: |Charles Kleingrothe, 1907: |"Fed. Malay Stat. 3: Nursery & 6 Years Old Plantation / Tapping 12 & 15 Years Trees, 1907").

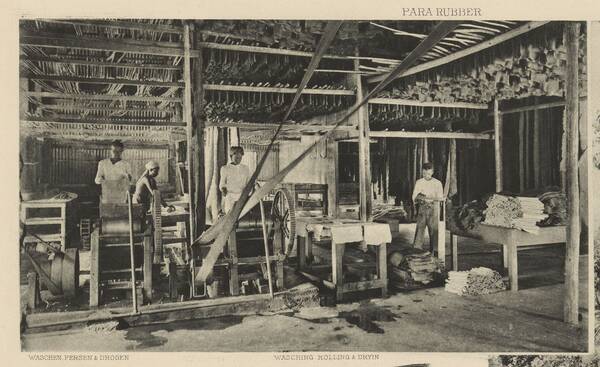

Pemprosesan Getah

Kaedah pemprosesan getah ketika itu: “Showing the interior of an estate factory, with workers operating the machinery which squeezes moisture from the latex and forms it into strips. With bundles of rubber hanging from the ceiling.” (Cambridge University Library: |"Para rubber planting. Washing, rolling and drying, 1907". Gambar: |Charles Kleingrothe, 1907: |"Fed. Malay Stat. 4: Washing, Rolling & Drying / Seed Explosion of the Fruit (Drawing at the Bot Garden) / 23 Years Old (Linsum Fst) 1907").

1908-09-23: Keadaan Industri Getah Dunia

| Tarikh | Butiran Keratan | |

|---|---|---|

| | 1908.09.23 | "RUBBER NOTES". The Straits Times, 23 September 1908, Page 2 |

Hal Ehwal Semasa Industri Getah. (Bukan Malaya, tapi tetap menarik untuk dibaca).

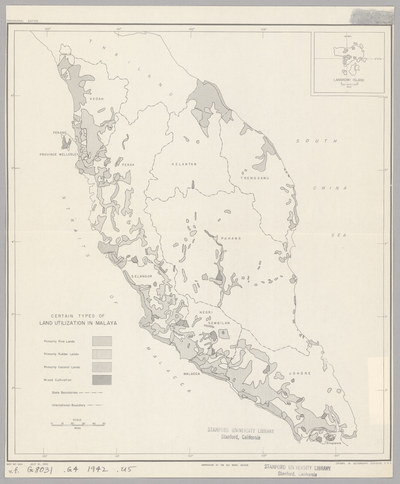

Peta Guna Tanah Malaya 1942

Peta guna tanah Malaya 1942 (United States. Office of Strategic Services, 1942: |"Map no. 678, July 9, 1942").

Pekerja Ladang

1900-an: Buruh Berhutang dari Selatan India

Sejak dari awal lagi, sumber utama tenaga pekerja ladang getah adalah dari selatan India (Madras), dan kebanyakannya adalah dari kalangan masyarakat rentan berlatar kasta rendah, yang sering dilanda kemiskinan dan kebuluran akibat bencana alam serta sistem percukaian yang menindas. Sebagai usaha mencari jalan keluar, mereka sanggup menjadi “buruh berhutang” (indentured worker) melalui ejen-ejen buruh yang datang ke kampung-kampung mereka. Ejen-ejen in menawarkan wang pinjaman pendahuluan untuk mereka berhijrah ke ladang-ladang di Malaya, dan bekerja untuk majikan tertentu sepanjang waktu yang ditetapkan (biasanya 3 tahun), lalu sebahagian pendapatannya digunakan bagi membayar balik hutang pinjaman tersebut, dalam waktu yang ditetapkan. Selagi tempoh kontrak belum tamat, dan/atau hutang belum dapat dilangsaikan, mereka terpaksa terus bekerja di bawah majikan yang sama, dan boleh ditangkap dan didakwa sekiranya bertindak meninggalkannya:-

“By 1906, British capitalists were seizing the opportunity to make fortunes by investing in Malayan rubber plantations. Companies sometimes paid dividends of over 200 per cent, and agency houses amassed huge profits in the buying and selling of plantations. Apart from some ups and downs depending on the world rubber price, the area continued to expand until halted by the world depression which began in 1929. In that year, the rubber plantation companies were employing about 258, 000 coolies on their estates. Most of these men and women – about 80 per cent – came from Southern India, where Madras Presidency, like much of the rest of India, was a fertile recruiting ground. Frequent failure of the monsoon resulted in drought and famine; the system of taxation the British Raj imposed exacerbated poverty and indebtedness. The people most affected were Untouchables and of the lowest castes. Recruitment for employment in Malaya was often an alternative to starvation, both for themselves and the families they left behind. Until 1912, most Indians were recruited under indenture. Agents for recruiting firms visited villages, offered a cash advance to men and sometimes women willing to put their thumbprint to an indenture agreement. This provided that the recruit would work for a specified employer (and no-one else) for a fixed period (usually three years) to his employer’s satisfaction, and for a fixed wage. The cash advance was a charge against the money the coolie would earn; if he succeeded in repaying it within the period set by the indenture he was free to leave the plantation; if not he had to remain and work off his debt. If he left before he had acquitted his debt and served his time, he was subjected to criminal penalties.” (James Hagan, Andrew Wells @ University of Wollongong, 2005: |"The British and rubber in Malaya, c1890-1940", m.s.3-4).

“In the case of Indian labour, the sub-imperial India Office and the Federated Malay States (FMS) government jointly planned and regulated South Indian labour’s employment in the FMS with the approval of the Colonial Office in London. Indian migrants were mainly low-caste men, mainly from the Tanjore, Trichinopoly and North Arcot districts in South India. These districts were particularly vulnerable to drought, while famine and landlessness was widespread. Migrant workers’ travel and related costs were paid by the labour intermediaries (or prospective employers) and migrants were required to work for employers for a fixed period until they had repaid their debts. … In the indenture system for Indian workers, Malayan planters initially used the services of one of the labour recruitment firms in Negapattinam or Madras, or sent their own agents to South India to recruit labourers directly. Agents advanced money to prospective migrants for transport and other expenses on the stipulation that they sign a contract on arrival in Malaya. The men were then considered to be under indenture to their employers for a fixed period. Initially, this ranged from 3 to 5 years, although it was fixed at 3 years following enforcement of the 1904 Labour Ordinance (Tinker 1974, 179).Workers were given the option of being re-indentured for a further period, or were released from indenture after finishing their contracts, on the condition that they had paid off their debts.Wages were fixed at the time of recruitment; they were not negotiable and only paid after deducting employers’ recruitment costs. Indian workers were unfree in their binding to specific employers who penalized them to enforce labour contracts, while any violation of contract was regarded as a criminal, rather than a civil offence.” (Amarjit Kaur, 2014: |"Plantation Systems, Labour Regimes and the State in Malaysia, 1900–2012" (PDF), m.s.7-8).

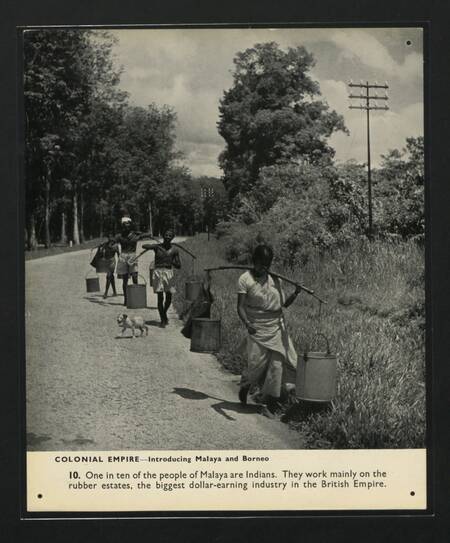

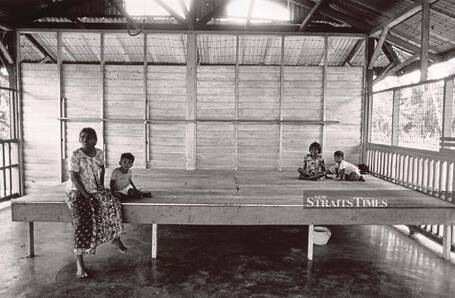

Sebahagian besar tenaga kerja India ketika ini ialah kaum lelaki bujang. Sebelum tahun 1900, nisbahnya 7.2 pekerja lelaki bagi setiap pekerja wanita. Ini kerana wanita dan lelaki yang berkeluarga tidak digalakkan menjadi buruh berhutang. Kerjanya berat, dan gaji hariannya rendah dan bergantung kepada harga getah serta kos sara hidup semasa. Mereka dibekalkan kediaman kecil, bekalan hidup, serta khidmat perubatan: “The Indian plantation workforce was predominantly male. For every 100 acres under Western rubber cultivation, there were 15–20 workers, the vast majority of whom were men. According to Saw (1988, 20–1) there were probably more than 7.2 Indian males for every Indian female plantation worker in the late nineteenth century, largely due to the indenture system. Both single women and married men were discouraged from indenturing themselves. Labour costs were split into two separate components, maintenance and renewal. Workers were paid a daily minimum wage determined both by the prevailing price of rubber and their dietary and subsistence requirements. As noted, companies also supplied basic accommodation (for single men only), subsidized provisions and occasional medical attention (Kaur 2012). Wages were low – the standard payment was for a single person – and working conditions harsh. Labour force renewal occurred traditionally largely through new hires.” (Amarjit Kaur, 2014: |"Plantation Systems, Labour Regimes and the State in Malaysia, 1900–2012" (PDF), m.s.10).

Disebabkan pemerasan dan penindasan yang berleluasa, telah lahir gerakan memansuhkan sistem perhambaan pekerja berhutang ini: “International support for unfree labour in any form dropped off markedly, however, in the early twentieth century after the founding of the Congo Reform Association in 1904. The publications of the British journalist E.D. Morel and the Irish diplomat Roger Casement exposed the enslavement, torture, and mutilation of rubber workers in the Belgian Congo, which fuelled an international campaign in defence of the human rights of colonial subjects. Since the British government commissioned, published, and defendedCasement’s report, it was in a weak position to protect its own practice of indentured labour, which had come under attack, too. During the first decade of the twentieth century, Indian nationalists had mounted fierce assaults on indenture in South Asia as well as in South Africa, while local opposition to the practice grew in Natal, Mauritius, Assam, and Trinidad. Workers’ groups took to the streets, while colonial officials felt free to point out abuses in the system. The Anti-Slavery and Aborigines’ Protection Society added its voice to an international anti-indenture campaign, which helped to abolish the practice in British Malaya in 1910 and in remaining British colonies by 1920.” (Lynn Hollen Lees, 2017: |"Planting Empire, Cultivating Subjects: British Malaya, 1786–1941, pp. 171 - 217).

1910-an: Buruh India, Jawa, dan Cina

Tenaga Buruh India: Sistem Kangani

Menjelang tahun 1910-an, pihak kerajaan, melalui Lembaga Siasatan Parr, telah mendapati banyak kelemahan pada sistem ejen buruh sebelum ini. Ianya sering terdedah kepada rasuah dan penipuan, buruh sering berpindah majikan, dan tenaga buruh yang dibekalkan masih tidak mencukupi. Maka ianya digantikan dengan sistem migrasi buruh secara “bebas”, iaitu dibiaya oleh tabung “Indian Immigration Fund”, hasil sumbangan para majikan, dengan kadar mengikut bilangan pekerja semasa mereka. Pencarian tenaga buruh dijalankan oleh pekerja ladang itu sendiri, yang dipanggil “Kangani”. Para kangani ini lazimnya mencari sumber pekerja dari kalangan kaum keluarga, kasta, serta perkampungan mereka sendiri. Dalam perjanjian sistem kangani, buruh tidak berhutang apa-apa, dan tidak terikat dengan mana-mana majikan. Mereka cuma perlu memberi notis berhenti kerja sahaja pada bila-bila masa. Hasilnya, jumlah pekerja migran dari India bertambah dengan pesat, dan para pengusaha ladang mendapat manfaatnya. Limpahan bekalan buruh menyebabkan kadar gaji buruh yang rendah, dan pertalian keluarga di antara para pekerja serta Kangani mereka, menyebabkan mereka cenderung untuk setia dengan majikan yang sama: “By 1910, at the time when the number of rubber plantations was increasing rapidly, plantation owners were discovering that the indenture system was unsatisfactory. The Parr Inquiry of that year found that the system lent itself to corruption and fraud, which was expensive; despite the ordinance on crimping, coolies who risked criminal punishment by running away readily found employment with another estate, often at a higher wage. Moreover, the coolies were not coming in sufficient numbers, because other destinations were more attractive. The main purpose of the indenture system was to secure a reliable supply of labour to the plantation employers at the lowest possible wage. The Parr inquiry found it was failing to do this. Parr’s solution was to abandon recruitment by indenture and replace it with a system of mass immigration by ‘free’ labourers. The Government accepted the recommendation, and the Indian Immigration Fund, already established, would pay for the passages of ‘free’ coolies to Malayan ports. Employers contributed to the Fund according to the number of Indian coolies they employed. They hired their labourers not through professional agencies, but via Kanganis – senior plantation employees who travelled to India and recruited among fellow villagers, tribe, family and caste. The recruit did not sign an indenture, and in law was free to leave his employment after giving due notice. Kangani recruitment in combination with assisted passages brought hundreds of thousands of coolies to Malaya and largely achieved the employers’ objectives. Sheer numbers reduced the wages of plantation labour to a minimum, and the social ties and obligations established by Kangani recruitment helped keep the coolies working obediently on the one plantation for long periods.”

Para buruh dipantau oleh pelbagai akta dan ordinan sejak tahun 1870-an. Bagi buruh dari India khususnya, Kod Buruh 1912 (kemudiannya diperkukuhkan oleh akta-akta lain) menetapkan dasar-dasar berkaitan bilangan jam bekerja, gaji, kediaman dan kemudahan, dan sebagainya. Dasar-dasar ini dikuatkuasakan oleh Jabatan Buruh dengan diketuai pegawai pengawalan buruh, yang membuat lawatan berkala di premis ladang dan berupaya menutupnya sekiranya didapati menyalahi kod atau akta tertentu. Pegawai pengawal ini turut menerima aduan para buruh, dan menjatuhkan hukuman terhadap para penyelia yang didapati menzalimi mereka: “Both systems of labour were regulated by various acts and ordinances, which dated from the 1870s. Those relating to Indians were consolidated into the Labour Code of 1912, which laid down certain requirements regarding working hours, pay, housing and accommodation, which were supplemented later by other Acts. There was a Labour Department headed by a controller of Labour, who could inspect premises, and even close them down. The Controller could also hear complaints from coolies, and he sometimes prosecuted overseers for violence against them.”

(Sumber: James Hagan, Andrew Wells @ University of Wollongong, 2005: |"The British and rubber in Malaya, c1890-1940", m.s.4).

“Kangani means ‘overseer’ or ‘foreman’ in Tamil. It was the kangani who recruited workers from his home area and facilitated their transition into their workplaces in Malaya. As noted above, the kangani system had been employed earlier in the Straits Settlements but became increasingly popular, since by using it employers could bypass commercial or independent intermediaries. Plantation companies also preferred this system since with it, the incidence of workers absconding from the plantation declined over time. Arguably, the fact that the kangani received ‘head money’ for each day worked by the workers (which he lost if workers deserted) meant he had a vested interest in ensuring that they remained (Sandhu 1969, 101; Kaur 2012, 232–4). Moreover, he also related to labourers in his roles as supervisor, plantation storekeeper and moneylender, and workers were often indebted to him. Arudsothy (1986, 75) argues that the kangani system was a ‘variant of the indenture system, as in effect, the debt–bondage relationship between servant and master still remained, although indirectly’. … Increasing demand for labour by plantation companies and the Malayan government for public works in the years immediately preceding the First World War marked a turning point in Indian labour recruitment and strengthened the position of intermediaries. In 1907, the government’s Tamil Immigration Fund Ordinance established an Indian Immigration Committee (IIC) to administer a Tamil Immigration Fund to assist South Indian labour migration (Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Adviser 1907). The Ordinance incorporated three mechanisms. First, an official system or structure was established to oversee and regulate employment of ‘free’ South Indian labour. Recruitment of workers continued to be assigned to licensed kangani. Second, a Tamil Fund (renamed the Indian Immigration Fund in 1910) was launched to provide free travel for Indian labourers to Malaya. Third, the government introduced a quarterly fee (or levy) on all employers of Indian labour to meet labourers’ travel and related costs. This was based on aggregate ‘man–days’ worked and amounted to about M$29.39 per head in 1912 (Stenson 1980, 18).The IIC comprised representatives of the main government departments and the major plantation employer groups. The IIC monitored the number of recruiting licenses given to the kangani and supervised the distribution of recruiting allowance or subsidy provided to migrants. Essentially, this legislation resulted in Indian migration evolving into two distinct categories, namely, recruited and non-recruited (spontaneous) migration. However, whether migrants were recruited under the kangani system or travelled independently, they now arrived as persons free of debt obligations. This policy accelerated migration as prospective labour could present themselves at emigration depots in India for assisted migration to Malaya. Concurrently, the indenture system for Indians was phased out in 1910, with the last contracts ending in 1913. These developments reflected a paradigm shift, a move away from labour circulation to a permanently settled Indian labour force on plantations and elsewhere. Thus Indian workers recruited under the Fund’s sponsorship were afterwards confined to plantations or restricted to government public works projects in emerging townships. Moreover, although arriving in Malaya without any debt obligations, they continued to be considered under contract to specific plantations and toiled under the supervision of the kangani.” (Amarjit Kaur, 2014: |"Plantation Systems, Labour Regimes and the State in Malaysia, 1900–2012" (PDF), m.s.8-9).

Tenaga Buruh Jawa: Buruh Berhutang

Kepadatan penduduk yang tinggi, serta kemiskinan yang berleluasa di Jawa pada zaman kolonial Belanda, menyebabkan ramai warganya merantau demi kelangsungan hidup. Bagi menampung keperluan pekerja ladang yang tinggi di Malaya, kerajaan British membuat perjanjian dengan kerajaan Belanda di Jawa bagi pembekalan “buruh berhutang” dari Jawa secara sistematik. Di bawah enakmen tahun 1909, kerajaan Belanda menyediakan kontrak kerja buruh berhutang ini untuk tenaga buruh dari Jawa sehingga tahun 1932, lama selepas kontrak sebegini dimansuhkan bagi pekerja India dan Cina: “From a comparative perspective, South-East Asian countries may possibly be divided into ‘labour-scarce’ and ‘labour-surplus’ countries, and this situation had important implications for the growth of wage labour and colonial labour policies. There were two extremes in this categorization – Malaya and Java. In Malaya, landlessness and rural deprivation among the Malays was practically non-existent and they largely shunned wage work during the colonial period. But in Java, with its huge, poor population, non-farm employment was crucial for survival strategies, and Javanese workers moved around during the colonial period to eke out a living. Thus while Java has been a labour exporter since colonial times, Malaya/Malaysia has been a labour importer. … The importance of rubber in Malaya’s economy increased demand for labour and anxiety over likely Indian labour shortages subsequently led to Javanese labour recruitment. The Javanese were recruited as indentured workers, following an agreement between the Malayan and Dutch colonial governments (Jackson 1961, 127). Under the Netherlands Indian Labour Protection Enactment (1909), the Dutch stipulated written employment contracts for Javanese workers, who continued to work under indenture until 1932, long after this had been abolished for Indians and Chinese. Subsequently, attempts were made to recruit free Javanese labour with the assistance of Javanese workers resident in Malaya, but with limited success.” (Amarjit Kaur, 2014: |"Plantation Systems, Labour Regimes and the State in Malaysia, 1900–2012" (PDF), m.s.5-7).

Tenaga Buruh Cina: Sistem Kontrak

Sejak British bertapak di Pulau Pinang pada tahun 1786 lagi, pekerja migran Cina dibawa ke Malaya secara besar-besaran oleh ejen kontraktor buruh yang beroperasi di kampung-kampung sekitar Kwangtung, Fukien dan Kwangsi sebagai buruh berhutang. Sepanjang kurun ke-19, industri kontraktor buruh dan persatuan-persatuan kerjayanya, termasuk bilangan pekerja migran serta kadar gaji dan suasana kerja mereka, dikawal sepenuhnya oleh kongsi-kongsi gelap tauke-tauke kaya, seperti Ghee Hin dan Hai San. Walaupun kerajaan British menghapuskan sistem buruh berhutang pada tahun 1914, pekerja migran masih berhijrah secara persendirian, lalu masih menanggung hutang, dan masih terus ditindas di bawah sistem kontraktor buruh di Malaya. Mereka sering ditipu pusat perjudian, terpaksa membayar harga tinggi untuk makanan, candu, dan keperluan lain, serta terpaksa membuat pinjaman dengan kadar bunga yang tinggi: “Between the establishment of British rule in Penang in 1786 and the outbreak of the Great Depression in 1930, an unprecedented number of Chinese immigrants from Kwangtung, Fukien and Kwangsi came to Malaya in search of economic gains. These immigrants were recruited as cheap labour by professional agents engaged by lodging houses or more frequently by returned Chinese acting as contractors who operated in their own or surrounding villages in China. The transient workers were indentured to employers until 1914 when the indenture system was abolished; thereafter they were obliged to work out their debts incurred in getting them to Malaya. In either case they were subject to blatant abuses. Invariably they were cheated by 'crooked gambling dens' and forced to pay high interest for advances or exorbitant prices for food, chandu and other goods supplied by contractors. These abuses often prolonged the period of their employment under particular bosses or contractors; indeed, a great many simply failed to free themselves from the financial millstones round their necks throughout their stay in Malaya. In the nineteenth century the above employment system was sustained and maintained by the more wealthy and powerful of the Chinese towkays who were simultaneously heads of Chinese triad or secret societies, among the best known of which were the Ghee Hin and the Hai San. It was these society bosses who determined the volume of Chinese immigration to Malaya - the volume being expanded during booms and contracted during slumps. They also controlled the distribution of Chinese workers, their wage rates and working conditions in the country. For the skilled craftsmen additional constraints are exercised by the traditional trade guilds, then allies of powerful triad societies. Consisting of masters, journeymen and apprentices, and most common among the shoemakers, tailors, goldsmiths and carpenters, these guilds performed certain trade-union functions. They settled 'rates of wages, hours of work, holidays and terms of apprenticeship' and provided certain social amenities as accommodation and funeral benefits for members. Under the above restrictive employment system Chinese labour had little bargaining power even though the trade guilds did offer some form of protection to skilled workers.” (Yeo Kim Wah, 1976: |"The Communist Challenge In The Malayan Labour Scene, September 1936-March 1937", m.s.3).

Buruh dari negeri Cina diuruskan melalui sistem kontrak. Mereka dikumpulkan di asrama pekerja di pelabuhan negeri Cina, sebelum dibawa ke depoh kontraktor buruh di Singapura. Mereka bekerja di ladang di bawah kontraktor ini, dan ditempatkan di rumah kongsi yang dibina berdekatan ladang yang melanggan perkhidmatan kontraktor tersebut. Pada tahun 1931, buruh sistem ini meliputi satu pertiga daripada keseluruhan buruh-buruh ladang: “The Parr Inquiry also investigated the recruitment of Chinese labour, which differed from that of the recruitment of Indians. Chinese who were mustered in hostels in Chinese ports then travelled to a depot in Singapore, usually on the ‘credit ticket’ system, which obliged them to work for the ticket’s purchaser. This was always a labour contractor, who would assemble his coolies at the depot (often amid scenes of great disorder which bordered on riots) and take them to a kongsi house he had built on the estate of the plantation owner with whom he had contracted. Here, the coolies would work under his supervision, he would pay them, and the estate management would have no direct contact with them. Chinese employed on this contract system made up about a third of the plantation workforce in 1931.”

Kiri: “A boat arriving in Singapore with coolies, circa 1900. The coolies step out of the hold and stand on deck for a photograph taken by the German boat owner. This is a rare and valuable image because there are generally no photographs of early Chinese coolies. Coloured using modern image-processing technology, the photograph takes us right back to that boat deck a century ago, giving us a hint of how these coolies must have looked and felt upon arriving at their destination.”

Tengah: “A coolie ship arriving at the Kallang River in Singapore. This is a rare photo of a coolie ship, which also shows what the Kallang River used to look like. The ship is not a large one, and might have been transporting cargo as well as the coolies. Some of the cargo might have been transported directly to the Kallang River and not any of the quays, possibly because there were also cargo points at the Kallang River. However, there were no large wharf facilities at the Kallang River, and the ship had to be anchored in the river itself, with people and goods moved via floating bridges formed by smaller boats.”

Kanan: “View from a coolie boat looking across to the Kallang riverbank, with large wooden sheds filled with goods. The Kallang River is over 10 kilometres long, making it Singapore’s longest river. Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles built a trading centre at its lower course, and these wooden sheds were to store goods moving in and out. The photograph also shows a thick primary forest, Singapore’s greenery in its early days.”

Kiri: “A nice shot of the Kallang River taken from a coolie boat. For a long time, this river was an important place for the import and export trade. Ming dynasty Chinese porcelain has been found in it, showing its long history as a channel of international trade.”

Tengah: “A Chinese “agent” on board a coolie boat. His job was to recruit villagers back home to cross the sea to work. He also managed them and even travelled with them to make sure everything went smoothly. The Western bosses who brought in the coolies also needed the Chinese agents to pass on instructions. Written records say little about the agents; they are generally thought to be akin to foremen. But this photograph shows that some agents were quite well to do, almost like Chinese merchants. Some successful agents even rose to become international traders.”

Kanan: “Chinese immigrant workers at a rubber plantation. In the 19th century, British colonialists recruited labourers from the coastal Chinese provinces of Fujian and Guangdong to start rubber plantations. The early wave of Chinese immigrants to Singapore and the Malay Peninsula mainly comprised uneducated coolies.”

(Sumber gambar-gambar: Hsu Chung-Mao, 26 Jun 2020: |"An album of rare photos: From Chinese coolies to Singaporeans").

Di dalam sistem kontrak, buruh-buruh dari negeri Cina ini tidak dianggap bekerja di bawah ladang, dan tidak tertakluk oleh Kod Buruh dan tidak dipantau oleh pegawai Jabatan Buruh, sebagaimana buruh-buruh India. Kebajikan mereka dipantau oleh para pegawai “Penjaga Orang-Orang Cina” (Protector of Chinese), yang dilantik kerajaan. Namun pegawai ini tidak berupaya memantaunya dengan baik, oleh kerana gejala penindasan yang berleluasa dalam sistem buruh kontrak ini: “Administrative arrangements for the supervision of Chinese labourers were different from those applying to Indians. Since the coolies worked under a contract system, the management of the plantation was not their employer in law, and the detailed regulation of the Labour Code did not apply to Chinese plantation workers. There was instead a Protector of Chinese, with deputies in the various Federated Malay States. The system of contract labour lent itself to serious and frequent abuse, which the overworked staff of the Protector could do little to check, but this did not deter Chinese from coming in numbers that the Government considered adequate.”

(Sumber: James Hagan, Andrew Wells @ University of Wollongong, 2005: |"The British and rubber in Malaya, c1890-1940", m.s.4).

“A third migrant labour group comprised Chinese immigrants, but the Malayan government was not involved in their recruitment or employment, although it did appoint a Protector of Chinese to look after their interests. The Chinese were recruited and managed by Chinese labour contractors and regularly moved around in search of better wages. Contractors rather than estates were responsible for workers’ accommodation and looked after their necessities.” (Amarjit Kaur, 2014: |"Plantation Systems, Labour Regimes and the State in Malaysia, 1900–2012" (PDF), m.s.7).

1920-an: Pembelaan Hak Pekerja

Pembelaan Hak Pekerja India

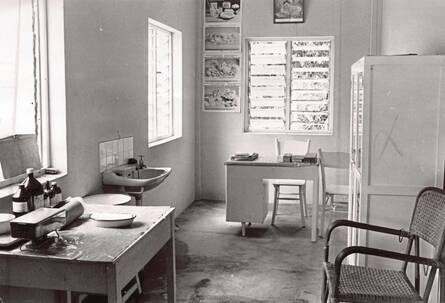

Pada tahun 1909 dan 1910, Jabatan Buruh telah menggubal Kod Buruh, yang menetapkan gaji minima, had waktu bekerja, dan piawaian kesihatan. Pekerja harus disediakan perumahan, penjagaan mutu kebersihan, serta bekalan air bersih pada tahap sewajarnya. Khidmat hospital, kakitangan perubatan, serta ubat-ubatan harus diberikan secara percuma. Kod ini dikuatkuasakan melalui tinjauan ke ladang-ladang, dan bagi pihak yang tidak menurutinya, hak perolehan pekerjanya disekat. Namun hal ini mendapat perhatian rapi pihak kerajaan hanya kerana ianya menjadi simbol kemajuan serta hubungan penjaga bagi rakyatnya, bukan atas dasar pemberdayaan pekerja melalui kesatuan atau proses demokrasi dalam menjaga kebajikan pekerja: “The Labour Department, working together with the legislature of the Federated Malay States, moved to regulate working conditions in the rubber industry. Labour codes enacted in 1909 and 1910 set minimum wages, maximum hours, and health standards. Labourers had to have “proper” housing and sanitation, as well as “sufficient wholesome water.” Hospitals, medical personnel, and medicines also had to be provided free of charge. Niggling disputes over the meaning of “proper” and “sufficient” arose regularly, but Labour Department officials and health officers inspected the larger estates to ensure compliance, occasionally using their ability to block new hiring until problems were corrected. In addition, colonial officials were sufficiently invested in the issue of workers’ welfare to mount periodic investigations into employment conditions. As interest in sanitation as a sign of progressive colonial rule spread throughout the peninsula and as general standards rose, state inspectors nudged plantation managers to improve their physical environments. They took on the role of protectors of imperial subjects, denying the need for unions or democratic processes to safeguard workers’ welfare.” (Lynn Hollen Lees, 2017: |"Planting Empire, Cultivating Subjects: British Malaya, 1786–1941, pp. 171 - 217).

Pada tahun 1920-an, Persatuan Peladang Malaya (Planters’ Association of Malaya (PAM)) telah berusaha mengurangkan campurtangan kerajaan dalam kegiatan mereka, mengamalkan interpretasi Kod Buruh secara minimalis, menyekat kebebasan pasaran buruh melalui ordinan serta persetujuan sesama ahlinya, serta memastikan bekalan buruh yang tinggi (malah menyekat kadar penghantaran pulang lebihan tenaga kerja), agar kadar gaji dapat dikekalkan di tahap yang minima: “The guiding principles of the Association’s industrial policy were three fold: to limit the interference of the Government in what its members considered were purely matters of domestic management on their plantations, which meant a minimalist interpretation of the Labour Code; to restrict the movement of ‘free’ labour by ordinances against ‘crimping’ and by internal agreements among members; and to keep the supply of ‘free’ labour as large as possible to depress wages to a minimum. Even in 1931, in the depths of the Great Depression, the Planters’ Association attempted to slow the rate of repatriation of unemployed Indian labourers for as long as possible.”

Usaha-usaha sebegini tidak disenangi oleh kerajaan India ketika itu, dan di atas permintaan mereka, Jawatankuasa Imigrasi Buruh India telah melantik wakil dari kerajaan India, yang menjalankan siri siasatan terhadap ladang-ladang di Malaya bagi menetapkan kadar gaji minima yang mencukupi. Cadangan gaji minima pihak Persatuan Peladang akhirnya dipersetujui, dengan syarat pihak peladang menyediakan sebidang tanah kecil seluas 1 / 16 ekar bagi setiap keluarga buruh menternak dan bercucuk tanam, bagi menampung keperluan hidup mereka: “The Association’s low wage policy had brought it into direct and chronic confrontation with the Agent of the Government of India in the 1920s. Following the Montague-Chelmsford reforms of 1918, the Government of India became much more amenable to the pressures of the Indian National Congress. Congress members took a keen interest in the employment of Indians abroad, and especially their wages. After some negotiation, the Government of the Federated Malay States agreed to the appointment to the Indian Immigration Committee (which administered the Indian Immigration Fund) of an Agent of the Government of India. The Committee then proceeded to conduct a series of inquiries whose purpose was to set wages for certain districts in the FMS. The Planters’ Association presented statistics to the Committee to demonstrate that the wages it proposed allowed coolies to achieve the standard of nutrition necessary to help keep them in healthy working order. The Committee accepted this minimal standard, and set wage rates accordingly. The Government encouraged the coolies to contribute to their own subsistence by requiring plantation owners to set aside very small plots (one sixteenth of an acre) on which the longer serving coolies might graze animals or grow food, a concession the estate owners were reluctant to make.”

Pada tahun 1928, kadar gaji minima ketika itu ialah 50 sen sehari bagi buruh lelaki, dan 40 sen sehari bagi buruh wanita.

(Sumber: James Hagan, Andrew Wells @ University of Wollongong, 2005: |"The British and rubber in Malaya, c1890-1940", m.s.5).

Pada tahun 1922, hasil perjuangan kelompok nasionalis dan reformis sosial di India bagi membela hak dan kebajikan pekerja India di Malaya, kerajaan India telah menggubal Akta Penghijrahan India (Indian Emigration Act), yang ditambah dan dikemaskini dari semasa ke semasa. Akta-akta ini menetapkan keadaan kerja dan hidup pekerja yang sepatutnya, dan dipantau bersama oleh Jabatan Buruh kerajaan Malaya, bersama wakil kerajaan India. Kadar gaji ditetapkan mengikut lokasi dan keadaan ladang, kos sara hidup dan kegiatan budaya, dan berkadar sesuai untuk simpanan waktu sakit dan hari tua. Bagi membantu meringankan beban hidup pekerja, pemilik ladang digalakkan untuk membuka kedai keperluan asas berharga borong di ladang masing-masing, dan menyediakan sebidang tanah kecil bagi kegiatan bercucuk tanam dan penternakan untuk sokongan hidup ketika musim-musim kemerosotan. Di samping itu, pekerja dibahagikan kepada beberapa klasifikasi: Penoreh getah (berkemahiran tinggi), pekerja kilang, dan pekerja ladang (berkemahiran rendah), dengan kadar gaji yang berbeza. Selain itu, golongan wanita dan remaja dibayar gaji yang lebih rendah:-

“By the early 1920s, Indian nationalists and social reformers had become vocal in their demands for improved working conditions for overseas Indian workers and focused on the issue of continuing Indian emigration. Hence in 1922 when the Indian Emigration Act was scheduled for enforcement in India, the question arose as to whether Indian emigration to Malaya should continue after March 1923 (when Malaya was scheduled to fall under its provisions). … The various Indian Emigration Acts governing Indian migration to Malaya prescribed workers’ wages and working and living conditions. Plantation workers came to be categorized into three groups on the basis of tasks/skills: rubber tappers, factory workers and field workers. Tapping was regarded as skilled work, while factory and field work were considered less-skilled or unskilled. In the early 1920s the principle of a standard wage (as opposed to a minimum wage) was established, and factors such as the locality of estates and the health conditions influenced wage determination. Workers’ wages were also determined on the basis of a standard budget calculation that included the cost of groceries, clothes, festival preparations and household goods. The standard wage was understood to be sufficient to maintain the plantation worker ‘in a tolerable state of comfort and allow for savings, sickness and old age’ (Ramasamy 1994, 32). Planters were also advised to reduce labourers’ cost of living by providing basic necessities at wholesale prices through estate shops. Moreover, workers were encouraged to grow their own vegetables and raise poultry and livestock during slack periods. Women and children were invariably paid lower wages than men, since wages were established on the basis of job classification, age and gender (Kaur 2004, ch. 4).”

“In the 1920s and 1930s, while Indian workers were the most affected by repatriation and, for those who stayed behind, drastically reduced standards of living, this period also saw both reduced intervention by official bodies (e.g. the Labour Department) to protect labour’s interests and a decline in authoritarianism and paternalism on the plantations. … First, an important stipulation in the Indian Immigration Act of 1922 resulted in the appointment of an Agent of the Government of India to Malaya, whose duties included inspection of plantations and other worksites where Indians were employed, compilation of annual reports on workers’ living and working conditions, and recommendations for improvement on plantations (Ramasamy 1994, 32–4; Kaur 2006; Kaur 2012). Additionally, the Agent served as India’s representative and advocate in Malaya.”

Antara tuntutan kerajaan India di dalam Akta Emigrasi India 1922 ialah nisbah pekerja migran perempuan dan lelaki yang lebih seimbang (1 perempuan: 1.5 lelaki). Namun kadar perubahannya amat perlahan (1901: 1:5.8, 1921: 1:2.5, 1931: 1:2.1, 1947: 1:1.6). Di peringkat akhir, majikan menyediakan khidmat penjagaan anak dan sistem persekolahan berpengantar Tamil, lalu menggalakkan lagi kemasukan tenaga pekerja wanita. Oleh kerana gaji yang masih rendah, lazimnya semua ahli keluarga yang cukup umur bekerja di ladang yang sama: “Since the demand for Indian labour was still considerable, the colonial government implemented reforms with implications for the ensuing Indian sex ratio in Malaya. The colonial government conceded to pressure by adopting Rule 23 of the Indian Emigration Act (Act VII of 1922), which stipulated that there should be at least one female emigrant for every 1.5 males assisted to immigrate as labourers to Malaya. Although in line with the permanent settlement paradigm and with the increasing differentiation and specialization of plantation work (see below), the Malayan government was very slow in implementing this condition. Generally, the ratio of Indian women to Indian men in Malaya increased at a very slow rate, from 1:5.8 in 1901 to 1:3.2 in 1911, 1:2.5 in 1921 and 1:2.1 in 1931, before eventually reaching 1:1.6 in 1947 (Ramachandran 1994, 32). The proportion of (mostly) Indian women workers employed in large-scale agriculture rose from 4.4 per cent in 1911 to 32 per cent in 1947. Eventually, employer-provided basic childcare services further facilitated Indian women’s participation in the paid workforce. Additionally, a rudimentary (Tamil) school system for children was introduced at this time. Since wages in the rubber industry were insufficient for the family’s requirements, almost all working-age members sought employment on the plantation.”

(Sumber: Amarjit Kaur, 2014: |"Plantation Systems, Labour Regimes and the State in Malaysia, 1900–2012" (PDF), m.s.10-11).

Pembelaan Hak Pekerja Cina

Pada tahun 1920-an, kerajaan British berjaya mengurangkan pengaruh kongsi-kongsi gelap dalam urusan pekerja migran Cina. Kod Buruh tahun 1912 pula berjaya mengurangkan penindasan. Lebih ramai pekerja berjaya melangsaikan hutang dan mula menetap sebagai pekerja bebas dan membina keluarga tempatan. Mereka menjadi lebih arif tentang hal ehwal suasana kerja di sini, dan lebih bersedia untuk tawar-menawar berkenaan kadar gaji serta hal-hal kebajikan yang lain: “Around the turn of the century social change began to erode a great many of the constraints within the Chinese employment system. Along with the extension of direct British control over the Chinese community, the triad societies were banned in 1890. By the 1920s British action had liberated the bulk of Chinese labour from the societies' control. Meanwhile, a Labour Code was enacted in 1912 which eliminated or at least significantly reduced the abuses mentioned earlier. An increasing number of Chinese workers therefore, succeeded in discharging their debts and other obligations to employers and contractors. They joined the more mobile permanently-settled Chinese labour force that had begun to emerge in Malaya by the 1920s as a result of the growth of the local-born Chinese population and Chinese acquisition of an economic stake in the country. This local pool of Chinese labour was far better informed than immigrant Chinese about working conditions in Malaya. Being generally free from debts to Chinese contractors, they were also more independent and ready to bargain for their service.”

Pekerja Tionghua tempatan yang bebas ini kemudiannya mula bekerja di pelbagai sektor ekonomi, dan mula mengalami kesedaran kelas pekerja, dan membela hak-hak mereka masing-masing secara persendirian. Suasana ini menjadi latar penubuhan kesatuan-kesatuan sekerja moden pada tahun 1920-an: “The more mobile Chinese labour force found ample employment openings in the expanding economy and, in particular, the industrialisation of Malaya. Economic opportunities in turn enhanced labour consciousness. During the early twentieth century the emergence of the rubber and other industries, side by side with the thriving Singapore entrepot trade with its credit and financial institutions, created vital changes in the Malayan work environment. Skilled workmen could now secure a reasonable wage rate without the trade guild's protection. In any case the modern factory, relying on different types of labour, seriously hampered guild organisation based on a particular trade and frequently on workers from a single dialect group as well. As Gamba pointed out, the above paved the way for the emergence of the modern labour union in the 1920s.”

Pada tahun 1920-an, gerakan pekerja yang kuat di tanah besar Cina di bawah pimpinan Sun Yat Sen dan persatuan Kuomintang (KMT)), membawa pengaruh besar kesedaran kelas pekerja kepada warga Tionghua tempatan, melalui pergerakan pekerja-pekerja migrannya. Banyak kesatuan sekerja ditubuhkan ketika ini, bagi menyahut seruan mereka. Mulai 1925, timbul pula kesatuan sekerja di bawah gerakan komunis. Perjuangan mereka tidak terhad kepada hak dan kebajikan pekerja sahaja, malah matlamat akhirnya ialah penamatan kuasa British dan sistem kapitalis. Namun pengaruhnya agak kecil di Malaya, oleh kerana ia hanya digerakkan oleh warga Hainan, Cina, dan hanya bergiat dengan pekerja Tionghua sahaja: “Meanwhile, the rise of a strong labour movement in China after the First World War further boosted Chinese labour consciousness in Malaya. Sun Yat Sen, fully involved in the founding of a Kuomintang (KMT) - controlled labour federation in Kwangtung in the 1920s, urged Malayan Chinese to organise modern labour unions to fight for their rights. His advice was readily accepted as a great many Chinese came from Kwangtung, while others fell in line as part of their support for China's national goals. Understandably, many labour unions consisting exclusively of employees were formed at this time and were permitted registration under the Societies Ordinance after 1928. Around 1925 Malayan communists began to organise unions among Chinese workers through the formation of illegal mutual benefit associations. They aimed not only at uplifting worker welfare but also at bringing about the eventual destruction of British colonial rule and the capitalist system. Towards this end, communist activists established the Nanyang General Labour Union in May 1926. This organisation started with five Malayan labour unions with around 1,000 workers but by April 1927 had forty-two unions with 5,000 to 6,000 members in Netherlands East Indies, Siam, Sarawak and especially in Malaya. In Malaya these unions were small and led by almost exclusively Hainanese leaders. Following the formation of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) in 1930 the above labour federation was renamed the Malayan General Labour Union (MGLU) and was affiliated to the Pan-Pacific Trade Union Secretariat, a satellite body of the Comintern. Communist unions however were weakened by ruthless police attacks, lack of leaders, financial difficulties, and the complete disruption of the MCP in the early 1930s. The position of the MCP andits labour unions was thus explained during the Third Representative Conference in April 1930: 'As a matter of fact the organisation is only confined to a portion of the Chinese race, namely Hailams, thus causing uneven development of organisation. The anti-imperialist movement has not been spread far and wide and the influence of the party among the masses is not strong. Only a small number of labourers in Malaya are in our Party while a majority are under the influence of the Yellow Labour Unions'. In short, compared with the more fundamental forces at work, communist promotion of labour organisation paled in importance and up to 1936 the MGLU exercised no influence over the great majority of the labour unions.”

(Sumber: Yeo Kim Wah, 1976: |"The Communist Challenge In The Malayan Labour Scene, September 1936-March 1937", m.s.3-4).

1930-an: Zaman Meleset

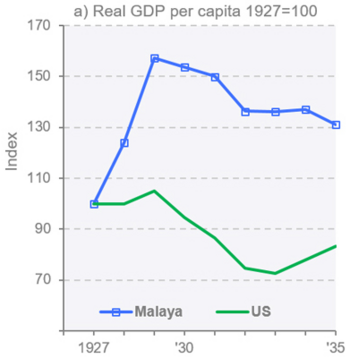

Pada Oktober 1929, pasaran saham Amerika Syarikat (AS) jatuh menjunam (digelar “Black Tuesday”), mengakibatkan Zaman Meleset, di mana Keluaran Dalam Negara Kasar (KDNK/GDP) dunia menyusut sebanyak 15 peratus di antara tahun 1929 hingga 1932. Ekonomi bandar musnah akibat runtuhnya industri, manakala warga luar bandar menderita akibat jatuhnya harga hasil tani. Golongan menengah kehilangan wang simpanan, pengangguran memuncak, dan kemiskinan berleluasa. AS paling teruk terkesan, dan GDP negara tersebut terus merudum sepanjang 1930-1933. Pada tahun 1939, GDP AS masih tidak dapat kembali ke paras asalnya. Antara kesan langsung krisis ekonomi di AS ini ialah merudumnya penjualan kereta di sana, dari 4.5 juta unit terjual pada 1929, kepada hanya 1.1 juta unit terjual pada 1932. Maka permintaan terhadap getah Malaya juga turut merudum. Akibatnya, ramai pekerja di Malaya (terutamanya di pantai barat) dibuang kerja dan ramai di kalangan buruh ladang India dihantar pulang ke negara asal mereka. Kadar gaji yang berkurangan menyebabkan ramai menderita, dan kadar kematian juga turut meningkat:-

“The Great Depression was a severe downturn in economic activity throughout the international economy during the 1930s. It started in 1929, soon after the US stock market crash of October 1929 - Black Tuesday. Financial turbulence and bank failures had predictable effects on the real economy. Between 1929 and 1932, worldwide GDP fell by around 15 per cent. A period of economic gloom permeated across the US and elsewhere. Urban economies were devastated as industries collapsed, and rural areas suffered as agricultural prices fell markedly. The middle classes lost their savings, unemployment levels were high and there was widespread destitution. The US experienced a particularly severe downturn (Figure 1a). US real GDP per capita fell each year throughout 1930-1933 (Table 1) and it failed to reach its 1929 level before the outbreak of World War II. By 1939, US real GDP per capita was still 5 per cent short of the level it had reached ten years earlier. Given that the US was the most important of Malaya’s export markets, the Depression had the expected dramatic effect on Malaya’s economic growth. The sale of passenger cars in the US declined from 4.5 million in 1929 to 1.1 million in 1932, with predictable effects on the US demand for Malayan rubber which tumbled. The scale of human suffering In Malaya during the Depression was immense, particularly in the west coast states. Workers were laid off, and many, especially Indian plantation labourers, were repatriated. Reductions in wages led to declines in living standards. Very high morbidity and mortality among all communities was another consequence.”

Kiri: “Figure 1 Economic impact of the Great Depression and the Great Recession”

Kanan: “Table 1 Real GDP per capita annual growth”

“In each of the four years following the Wall Street Crash, 1930-1933, Malaya’s real GDP per capita fell and, following only modest growth in 1934, fell again in 1935. The recession in Malaya was even deeper and more protracted than that of the US. Malaya’s experience in the 1930s was an excellent illustration of the well-known saying, ‘when America sneezes the rest of the world catches cold’. ”

(Sumber: Sultan Nazrin Shah, 2017: |"A TALE OF TWO CRISES: GREAT DEPRESSION AND THE GREAT RECESSION").

Keadaan Buruh India

Kejatuhan harga getah menyebabkan gaji minima yang ditetapkan sebelum ini (Lelaki: 50 sen sehari; Wanita: 40 sen sehari) tidak dapat diikuti oleh para pemilik ladang, dan hal ini turut dibiarkan oleh pihak kerajaan. Kesannya, ramai buruh berhenti kerja. Namun bagi mengekalkan bekalan tenaga pekerja, pihak kerajaan kemudiannya membuka semula imigrasi buruh pada Mei 1934, dengan kadar gaji yang rendah (Lelaki: 35 sen sehari; Wanita: 28 sen sehari): “This issue assumed even greater importance in the Depression, when the price of rubber slumped to a few pence per pound, planters began to dismiss their coolies, and a massive repatriation began. The wage standards set by the Immigration Committee in 1930 became irrelevant, with the connivance of the Government, and coolies left in droves. Yet it was obviously desirable to try to retain some part of the workforce against the time when recovery could begin. This occurred about 1934, and immigration resumed. … The Government had suspended assisted Indian immigration in 1931, but resumed it in 1934. Drought and famine in Southern India assured a plentiful supply, and in 1934 and 1935, over 155,000 Indians arrived in Malaya with a willingness that rendered recruitment by kanganis unnecessary. Intervention by the Controller of Labour secured employment for the immigrants at the rates of 35 cents per day for men, and 28 cents for women in May 1934.”

Keadaan ini tidak kekal lama, berikutan bantahan pihak Jawatankuasa Siasatan kerajaan India yang diketuai oleh V.N. Sastri, terhadap kadar gaji yang rendah itu. Mereka memutuskan untuk tidak lagi membenarkan imigrasi buruh ke Malaya, sehingga kadar tersebut kembali kepada tahap gaji minima yang pernah ditetapkan sehingga 1928 dahulu (Lelaki: 50 sen sehari; Wanita: 40 sen sehari). Pada mulanya, pihak pemilik ladang mengembalikan kadar tersebut, tetapi kemudiannya kembali menurunkannya. Akibatnya, kerajaan India menghentikan imigrasi tenaga buruhnya pada tahun 1938, menyebabkan ladang-ladang di Malaya bergantung kepada tenaga kerja tempatan dan buruh migran persendirian. Namun begitu mereka berjaya mengambil tenaga pekerja tersebut tanpa perlu menaikkan kadar gaji mereka. Menjelang akhir 1930-an, permintaan getah dan timah kembali meningkat, menyebabkan Persatuan Peladang menghantar petisyen kepada pihak kerajaan untuk membenarkan mereka menggunakan Tabung Imigrasi Buruh India untuk mendapatkan tenaga buruh dari Jawa pula: “ Over the next two years of strongly improving rubber prices, the UPAM refused to restore rates of pay to pre-Depression levels. In 1936, the Government of India pressed for an inquiry into the payment and conditions of Indian labourers in Malaya. Headed by V.N. Sastri, the Inquiry recommended restoration of the pay rates to the pre-Depression levels of 50 cents and 40 cents respectively. … In 1936, a Committee of Inquiry visited Malaya on behalf of the Government of India, and recommended that immigration cease unless the Planters’ Association restored wage rates and conditions to their 1928 level. It did, briefly, but then threatened to reduce them again; when it did, the Government of India prohibited State-assisted immigration to Malaya from 1938 thenceforth, planters had to rely on local residents and unassisted migrants to supply their workforce – which, as it turned out, they were able to recruit in sufficient quantity for estate owners not to have to raise wage rates significantly. A trade recession in 1938 helped them hold the line, but in September 1939, with demand for both rubber and tin booming, the UPAM petitioned the Government to use the Indian Immigration Fund to import Javanese labour.”

Menurut persepsi pemilik ladang dan kerajaan ketika itu, buruh-buruh India lebih mudah dikawal, dan sanggup bekerja dengan gaji yang rendah sebagaimana yang dikehendaki oleh Persatuan Peladang dan Persatuan Penanam Getah Malaya. Namun dalam masa yang sama pihak kerajaan perlu mengawal kemasukan migran dari India, berikutan sekatan dari kerajaan India menjelang akhir 1930-an. Oleh itu pihak kerajaan menggalakkan pengambilan mereka (termasuk kaum keluarga mereka) sebagai pekerja, melalui pemotongan kadar levi, bonus untuk pengambilan buruh tempatan, dan sebagainya: “So Government policy tended to concentrate on augmenting the supply of Indian labourers, who also had the advantage, from the point of view of both plantation owners and the Government, of being more docile. Encouragement of ‘free’ Indian immigration resulted in an adequate surplus of arrivals over departures in almost all the years up to 1930. The manager of the Immigration Fund also used it to encourage the recruitment of women and family groups by allowing their admission and employment at a lower rate of levy on the estate owner; and in the 1930s, the Fund actually paid a bonus to the estate owners on each coolie they recruited locally, provided they paid a small fee for their registration. The aim of these measures was to establish as quickly as possible a local plantation workforce born of Indian migrant parents. This would help solve a difficult problem for the Government: how to keep wages at something like the minimum rates the Rubber Growers’ Association and the Planters’ Association of Malaya wanted, without having to resort to the mass migration of Indians – which the Indian Government was increasingly reluctant to agree to, and in fact refused to allow from 1938.”

(Sumber: James Hagan, Andrew Wells @ University of Wollongong, 2005: |"The British and rubber in Malaya, c1890-1940", m.s.4-7).

Hasil laporan Sastri telah mendapat kritikan hebat dari masyarakat India, oleh kerana dapatan serta cadangannya yang tampaknya masih menyebelahi pemilik ladang. Golongan nasionalis India, diketuai Jawaharlal Nehru yang melawat Malaya pada Jun 1937, turut mempersoalkan cadangan kadar gaji yang masih rendah, juga lebih rendah berbanding pekerja Cina. Selain itu mereka menyeru pekerja India untuk membina kesatuan sekerja sendiri untuk memperjuangkannya: “In contrast, the Sastri report reaped a whirlwind of criticism from the Indian community, who felt that Srinivasa Sastri had not made any strong recommendation which could benefit them. … The shrewder Indian nationalists had made their own diagnosis of the situation and arrived at their own answer to Indian labour problems in Malaya. It appeared to them that the Indian labourers must organize and assert themselves in order to achieve better conditions. This view was driven home by Jawaharlal Nehru in June, 1937, during his visit to Malaya. His message was that every effort should be made to develop workers' unions in Malaya. He supported Sastri's recommendation that the kangany system of recruitment be abolished, but he went much further than Sastri in insisting on an immediate raise of Indian wages above the 1928 level and complete equality “between Indian and Chinese wages.” … Nehru refrained from making direct comments on labour conditions in Malaya, instead he made a strong appeal to Indian labourers to organise themselves.” (Tai Yuen, 1973: |"Labour unrest in Malaya, 1934-1941" (PDF), m.s.157-159).

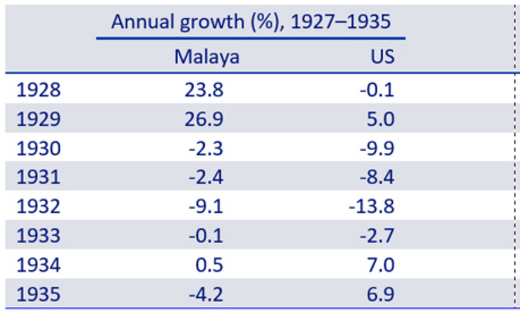

“The recruitment of assisted and voluntary Indian migrants in Malaya, 1844–1938”

Jelas di sini, gaji buruh India dimanipulasi oleh pihak syarikat perladangan, dan ditetapkan mengikut harga getah semasa: 1910: $6 sebulan, 1918: $13.90 sebulan, 1920: $12.40 sebulan, 1930: 40 sen sehari, 1931: 25-30 sen sehari, 1932: 20-25 hingga 25-28 sen sehari. Malah gaji buruh India di Malaya pada tahun 1930-an hanya tinggi sedikit berbanding buruh di India, manakala kos sara hidup di Malaya adalah 40% lebih tinggi. Di zaman meleset, pihak kerajaan cenderung menggunakan dana Tabung Imigrasi untuk menghantar pulang buruh India yang diberhentikan kerja. Setelah harga getah kembali pulih pada tahun 1936, kerajaan India dan Jabatan Buruh NNMB/FMS menyeru para peladang agar menaikkan gaji pekerja, sehingga ia dinaikkan kepada 40 sen sehari (pekerja lelaki) dan 32 sen sehari (pekerja wanita). Semenjak itu, isu gaji dan lain-lain hal pekerja menjadi fokus utama solidariti kelas pekerja, dan tindakbalas industri terhadapnya: -

Purata Kadar Gaji Pekerja Ladang Getah India 1910-1936

- 1910: 20 sen sehari

- 1918: 46 sen sehari

- 1920: 41 sen sehari

- 1928 (sebelum zaman meleset): Lelaki: 50 sen sehari, Wanita: 40 sen sehari

- 1930: 40 sen sehari

- 1931: 25-30 sen sehari

- 1932: 20-25 hingga 25-28 sen sehari

- 1934 (akhir zaman meleset): Lelaki: 35 sen sehari; Wanita: 28 sen sehari

- 1936 (harga getah pulih): Lelaki: 40 sen sehari; wanita: 32 sen sehari

“The fact that workers’ continuing employment and wages were tied to the price of rubber meant that plantation companies manipulated wages to their own advantage. For example, during the positive price trend of 1910–20, the average monthly wage rose from about M$6.00 (1910) to M$13.90 (1918) and M$12.40 in 1920. Benefits such as housing were valued at a further M$2.00 to M$2.50 per month (Thoburn 1977, 285). In 1930, daily wages were about 40 cents. However, they were reduced to between 25–30 cents at the end of 1931 and then to 20–25 cents in mid-1932. In December 1932, Indian wages ranged between 25 and 28 cents (Bauer 1948, 58). Satyanarayana (2002, 105–6) argues that the average earnings of an adult Indian male worker in Malaya in the 1930s were little more than those earned by an Indian agricultural worker in South India, since the cost of living was about 40 per cent higher in Malaya. As noted, the British preferred to repatriate Indian workers during the Depression rather than provide support for retrenched workers. Between 1930 and 1933, about 200,000 plantation workers were repatriated using Indian Immigration Fund funds (Tate 2008, 49). When the price of rubber improved, the Indian government and the FMS Labour Department lobbied the planters’ organizations to raise workers’ wages. The Indian government also bound granting of permission for additional labour recruitment to a wage increase. After initially resisting attempts to raise wages, planters in 1936 reluctantly agreed to daily wages of 40 cents for men and 32 cents for women (Kaur 2004, ch. 4). As demand gradually improved, wages and related issues became foci for working-class solidarity and industrial action.”

(Sumber: Amarjit Kaur, 2014: |"Plantation Systems, Labour Regimes and the State in Malaysia, 1900–2012" (PDF), m.s.10-11).

Keadaan Buruh Cina

Sepanjang zaman meleset 1930-1933, sebagaimana pekerja-pekerja lain, pekerja Cina menderita gaji dipotong, tidak dibayar, atau diberhentikan kerja, dan ada yang dihantar pulang. Kemudian kadar gaji mereka jatuh lebih rendah berbanding pekerja India, menyebabkan ladang-ladang mula menggantikan pekerja India dengan pekerja Cina. Keadaan kebajikan mereka yang sedia terabai, menjadi semakin buruk. Rumah-rumah kongsi mereka dibiarkan rosak dan tidak terurus. Kedai-kedai keperluan asas di lapangan, yang diurus oleh kontraktor sendiri, menjual barangan dengan harga yang mahal. Kedua-dua pihak kontraktor dan pihak pengurus ladang gagal memberi perhatian sewajarnya, disebabkan keutamaan-keutamaan lain serta kekurangan kakitangan dan kekangan kewangan yang meruncing pada zaman meleset. Pegawai Penjaga Orang-Orang Cina pula tidak berupaya mengurus masalah yang berleluasa ini:-

“…the depression had forced wages down to the bare subsistance level in the rubber, mining and other industries. In fact, Chinese labourers in rubber estates were often paid less than Indian coolies during the depression - a fact that ironically caused a substantial increase in the Chinese estate labour force. Many rubber estates such as those belonging to the Guthrie group had Indians repatriated to India at government expenses and then engaged Chinese. Drastic wage cuts and other difficulties were however, accepted by Chinese workers as inevitable exigencies of the time.”

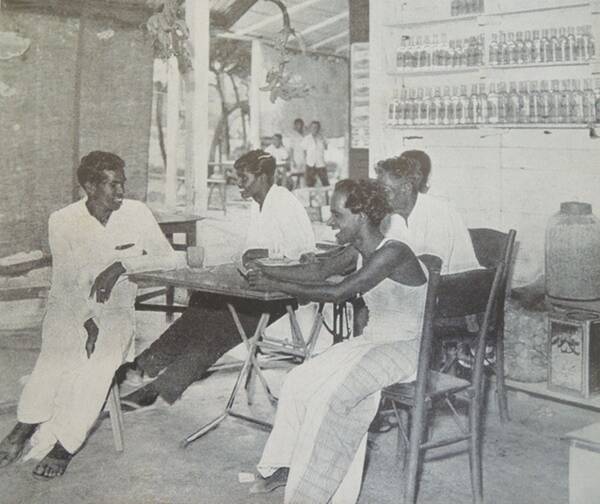

“One of the iniquities of the contract system was the general neglect of workers' welfare and living conditions. As the contractor engaged the labourers, he was made the employer under the Labour Code. Legally he was obliged to provide certain social amenities to workers such as the provision of proper accommodation, sanitary arrangements and water supplies. In practice these were provided, albeit haphazardly, by the estate, the mine or the factory. During the depression kongsi houses in mines and estates were left to rot and nothing had been done since to repair the revages of those difficult years. In 1938 Blythe reported that accommodation and sanitary arrangement in mines left 'ample room for improvement'. In most rubber estates the kongsi houses were in a most dilapidated state of conditions. In the Tanah Merah Estate in Negri Sembilan, an extremely bad example, the latrine of the kongsi house had collapsed and left unrepaired. The 130 inhabitants slept in one corner of the kongsi house because the roof leaked. Conditions elsewhere were superior but filth surrounded the kongsi houses in a large number of the estates. In one Negri Sembilan estate the coolie houses were 'well constructed and airy' but 'were simply hemmed in with filth and dirt and swarms of flies pounced on the rice which the tappers were eating.' But contractors cared little about living conditions in the estates or the mines, so long as these did not depress their earnings. The attitudes of managers were no better, preoccupied as they were in the case of rubber estates with the living conditions of Indian labourers. Their indifference was explained away on the grounds that they were unable to converse in Chinese or that Chinese resented interference into their affairs by outsiders. Nor did British officials act to improve the situation. The Chinese labourer was left alone, Governor Thomas explained, because he 'has always been able to take care of himself. When he has been dissatisfied with the treatment he has received, whether direct from his employer or at the hands of a contractor, he has gone to his employer or to the [Chinese] Protectorate and got his complaint adjusted or has indulged in a peaceful strike'. Little wonder that the Chinese Protectorate was neither sufficiently interested nor equipped with enough men to closely supervise and inspect the contract system. In short the workers were left in benign neglect - and in deep resentment- during the immediate post-depression years.”

“The contractor was, of course, no longer as powerful in the employment system as previously. His financial hold on labour had been drastically impaired as the recruits from the lodging houses no longer commenced work in a state of indebtedness. Still he was the stronger of the two parties and continued, albeit less blatantly, to ex- ploit labour. In certain ways the depression had had the effect of strengthening his authority over workers. The austerity drive then led to a drastic reduction in European staffs engaged in mines and estates. For instance, the 3800-acre Temiang Estate in Negri Sembilan cut its European staff from six officers to two. It was not common therefore, for a manager to take charge of more than two or three estates after the depression. Supervision of estates became more difficult and lax, and the manager was thrown back into greater dependence on the contractor. He found it harder to try to exercise control over the size of the task assigned to workers usually he did not even know what wage rate was paid the workers because the contractor kept his account books in Chinese. It was therefore, not uncommon for the contractor to underpay the labourers. The lack of supervision tended also to encourage another fairly widely practised abuse in rubber estates. Under the contract system the manager first paid the contractor who in turn remunerated the labourers. Usually labourers were kept informed of the dates of such payment by a notice posted in the estate. During the early post-depression years the hard-pressed and over-worked manager frequently overlooked this. Many contractors conveniently forgot to pay the labourers and after a few months absconded and disappeared. In such cases the victims often appealed to the Chinese Protectorate in vain.”

“It was common practice under the contract system for contractors to supply labourers with food, sundries and other goods. To continue in this business during the slump many contractors were compelled to rely on loans from shopkeepers in the nearby towns. The former in turn agreed to buy goods only from the particular shopkeepers con- cerned and to sell them to their labourers at exorbitant prices. In a great many estates, especially those in remote areas, labourers usually shopped in the contractor's kongsi house. Convenience was only partly responsible for this. Frequently workers did this to avoid offending the contractor and being saddled with difficult tasks of work. Hence, during the immediate post-slump days a large proportion of the labourers' earnings in many estates was re-circled to the contractor through the village shop.”

(Sumber: Yeo Kim Wah, 1976: |"The Communist Challenge In The Malayan Labour Scene, September 1936-March 1937", m.s.7-8, 10).

1937: Mogok Pekerja Tionghua

Sebelum ini, pekerja ladang tidak membantah atau mogok secara terang-terangan, oleh kerana kedudukan mereka yang rentan dan ketiadaan sebarang saluran pihak berkuasa atau kesatuan sekerja. Mereka membantah secara halus, tersembunyi, dan tanpa perancangan kolektif, contohnya dengan merosakkan premis, pokok getah, atau perkakasan: “Indian and Chinese workers were not always passive or docile, nor did they readily submit to the arbitrary rules of the colonial state or plantation companies. Generally, workers avoided open confrontation with unjust supervisors and voiced dissatisfaction through actions such as destruction of property, rubber trees or equipment – actions requiring little or no planning or collaboration.” (Amarjit Kaur, 2014: |"Plantation Systems, Labour Regimes and the State in Malaysia, 1900–2012" (PDF), m.s.12).

Pada tahun 1931, bagi mengawal imigrasi buruh Cina ketika itu, pihak kerajaan telah menggubal Ordinan Imigrasi (Immigration Ordinance), diikuti Ordinan Orang Asing (Aliens Ordinance) pada tahun 1933. Keduanya menetapkan kuota imigran Cina yang dibenarkan masuk ke Malaya. Kesannya, apabila ekonomi kian pulih dan permintaan buruh kembali meningkat, pihak industri sukar untuk menetapkan kadar gaji yang rendah, oleh kerana tiada lagi lebihan tenaga pekerja migran. Kesedaran kelas pekerja semakin meluas di kalangan para pekerja, terutama di kalangan pekerja bebas yang tiada bebanan atau ikatan hutang, serta golongan yang berpendidikan. Sementara itu, ordinan-ordinan ini hanya menyebut buruh lelaki sahaja, dan tidak menyatakan apa-apa tentang buruh wanita. Tambahan pula, harga tambang perjalanan dari negara Cina ke Malaya turut merudum. Faktor-faktor ini menyebabkan pertambahan pekerja wanita Tionghua secara drastik, dan mereka ini bercampur dengan pekerja bebas yang ada di Malaya sejak lama dan mula berkeluarga, dan tiada apa-apa ikatan hutang dengan kontraktor buruh Cina. Faktor-faktor ini menyebabkan mereka ini lebih sensitif terhadap pelanggaran hak-hak mereka, contohnya pembayaran gaji yang tidak cukup atau lewat. Pada tahun 1934, keadaan ekonomi industri kian pulih. Harga getah melonjak sebanyak 250 peratus. Para pemilik ladang menyalurkan keuntungan yang diperolehi untuk memulihkan keadaan mereka, dan keperluan tenaga pekerja kembali meningkat. Namun kadar gaji dan kebajikan pekerja masih tidak berubah. Ramai di kalangan para pekerja Cina kini menyedari hal ini, melalui bahan-bahan bacaan gerakan pekerja dunia yang disiarkan dalam akhbar Cina. Mogok mula berlaku pada tahun tersebut. Menjelang tahun 1936, kegiatan mereka menjadi semakin meluas dan radikal, kesan pengaruh Parti Komunis Malaya (asalnya cawangan parti komunis negara Cina pada 1920-an, sebelum ditubuhkan pada 1930), serta kesatuan sekerjanya Malayan General Labour Union (MGLU), yang giat menyusun aktiviti mogok di kalangan buruh Cina di ladang-ladang getah Malaya ketika itu. Kemuncaknya ialah mogok besar-besaran di ladang-ladang getah di sekitar Selangor pada tahun 1937, dan antara tuntutannya ialah manfaat untuk ibu-ibu selepas bersalin:-

“The above developments were brought to a head, so to speak, by the Malayan depression, 1930 - 33. For four harrowing years Chinese (as well as other) workers suffered drastic wage slashings and under-or unemployment. The more unfortunates were repatriated to China. The immigration restriction law of 1928, a result of the Kreta Ayer riots in 1927 and aimed at preventing political undesirables from landing in Malaya, was implemented in 1930 to ease the situation. But convinced that the future growth of the Malayan economy would be much slower, British officials called for more stringent control. The existence of a sizeable pool of local labour was considered sufficient to overcome any future drastic labour shortages in the country. In 1933 the government accordingly enacted the Aliens Ordinance which set an annual quota for Chinese immigration to Malaya. No longer could employers continue to keep wages down by increasing the volume of Chinese immigration to the country during booms. The result was a vast increase in the bargaining power and class consciousness of Chinese (and other) labour - a development further enhanced by India's banning of unskilled Indian labour immigration to Malaya in 1938. It should also be noted that the Aliens Ordinance accelerated the immigration of Chinese women to Malaya. Not only was there no quota set against female immigration but the ticket fares were substantially cheaper. The growing numbers of Chinese women in turn encouraged the expansion of the permanent pool of local labour. It also raised new problems such as the payment of maternity benefits - an issue during the strikes in 1936 - 7. The position in Malaya in 1935 was therefore, that bachelor labour had to a significant extent been replaced by family units living either in kongsis or on their own and that a stringently controlled Chinese labour market had given way to a virtually free one.”