Jadual Kandungan

Mogok Pekerja Ladang (1937)

Dirujuk oleh

Ringkasan Kejadian

Pada Khamis 11 Mac 1937, lebih 1,000 orang pekerja ladang (kebanyakannya kaum wanita Tionghua) telah melancarkan mogok di 9 buah ladang getah di Selangor iaitu Ladang Bangi, Connemara, Sungei Rinching, Prang Besar, Sydney, Bukit Tunggu, Balau, Hawthornden, dan Wardieburn (sekitar Bangi, Semenyih, Putrajaya, dan Kuala Lumpur kini). Mereka mengemukakan 19 tuntutan terhadap pihak pengurusan ladang-ladang tersebut, berkaitan kenaikan gaji harian, upah tambahan, hak dan kebajikan pekerja, manfaat ibu bersalin, kemudahan untuk anak-anak pekerja, dan lain-lain. Semuanya berjalan dengan aman, kecuali di Ladang Wardieburn, di mana sedikit kekecohan berlaku akibat salah faham di antara beberapa pekerja dengan seorang wartawan.

“Kesatuan Pekerja-pekerja Getah (RWU) Selangor dan Negeri Sembilan ditubuhkan dan diikuti dengan pembentukan Jawatankuasa Mogok Kajang pada bulan Mac 1937. Pada 7 Mac 1937, Jawatankuasa Mogok Kajang mengemukakan 19 tuntutan pekerja ladang kepada pihak majikan Ladang Bangi, Ladang Connemara dan Ladang Rinching. Tuntutan pekerja termasuklah kadar gaji minimum tetap $1 sehari ataupun kenaikan gaji sebanyak 50%, penambahbaikan keadaan perumahan, rehat kerja pada cuti umum, faedah kesihatan yang dibayar oleh majikan dan sebagainya. Pekerja-pekerja ladang getah di Selatan Selangor melancarkan mogok apabila pihak majikan enggan melaksanakan tuntutan pekerja. Aksi mogok ini mencapai kemuncak pada 22 Mac 1937, dengan lebih kurang 20,000 orang pekerja ladang di Selangor dan Negeri Sembilan bermogok. Pihak berkuasa bertindak dengan menangkap pemimpin-pemimpin pekerja.” (Belok Kiri @ Sosialis, 18 Februari, 2021: |"Kronologi Revolusi Dunia (Bahagian 2)").

“In early March 1937 Chinese rubber tappers in a number of estates in the Ulu Langat district, such as Hawthornden, Wardieburn, Sungei Rinching, Connemera, and Bangi Estates, struck to demand better wages and more decent working conditions (SSF, 1937). These strikes were fuelled by developments in the Bolton Estate strike in Cheras. In a workers' gathering a police detective who had infiltrated the ranks of the workers was exposed and assaulted. On learning of the matter a police party was dispatched to Bolton Estate and about 60 workers were arrested, though the leaders escaped. Anticipating that the leaders would return to claim the bicycles they had left behind, four police detectives were stationed there. However, contrary to the expectation of the authorities, the Bolton Estate labourers, angered by the police action, organized a protest march to Kuala Lumpur to demand the release of the 60. On their march the four detectives were assaulted when they tried to prevent their progress (SSF, 193 7).” (P. Ramasamy, 1994: |"Plantation Labour, Unions, Capital, and the State in Peninsular Malaysia", m.s. 54-56).

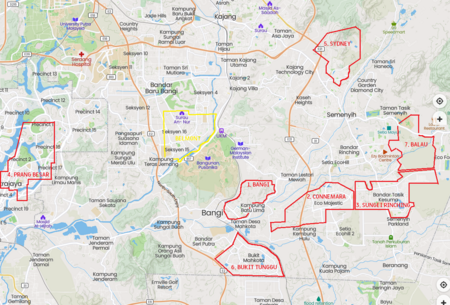

Penoreh getah Tionghua (Sebahagian daripada model-model pameran di Malaysian Chinese Museum, Sri Kembangan).

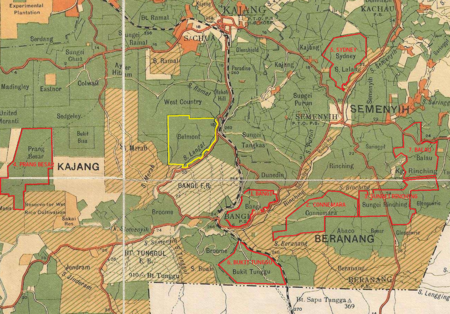

Peta sekitar daerah Ulu Langat, dengan ladang-ladang yang menyertai mogok wanita Tionghua pada 11 Mac 1937, ditandakan dengan sempadan dan label merah. (Kiri: 1937, Berdasarkan peta Edward Stanford @ F.M.S. Survey Department, 1929: "1929 F.M.S. Wall Map of Selangor (Kuala Lumpur)". Kanan: Kini, Berdasarkan peta Mapcarta - https://mapcarta.com/15815272):-

- BANGI (kini Bangi Avenue dan Crescent Park)

- CONNEMARA (kini Eco Majestic)

- SUNGEI RINCHING (kini Bandar Tasik Kesuma)

- PRANG BESAR (kini Putrajaya Precinct 1,2, dan 18)

- SYDNEY (kini Bandar Sunway Semenyih dan Taman Desa Mewah)

- BUKIT TUNGGU (kini Bukit Mahkota dan Bandar Puteri Bangi)

- BALAU (kini Mutiara Hills)

Dua lagi ladang yang tidak kelihatan di dalam peta (kerana lokasinya yang jauh ke utara, di sebelah utara Kuala Lumpur):- - HAWTHORNDEN (kini Wangsa Maju)

- WARDIEBURN (kini Danau Kota dan Taman Melati)

Sempadan kuning pula ialah Ladang Belmont, lokasi mogok/protes pekerja India pada 29 Januari 1937.

Liputan Peristiwa

Sekitar hari Isnin 8 Mac 1937, sebahagian pekerja Ladang Wardieburn telah berarak dengan mengibarkan bendera merah di sekitar ladang tersebut. Keesokannya (sekitar Selasa 9 Mac 1937), 60 orang pekerja Tionghua telah mogok dan enggan bekerja. Setelah berbincang dengan pegawai Penjaga Cina, mereka kembali bekerja pada keesokan harinya (sekitar Rabu 10 Mac 1937): “The first signs were seen early this week when factory coolies marched round Wardieburn Estate with a red flag. … The strike, it was stated, began two days ago when about 60 of the estate labour force, all Chinese, refused to turn up for work. The Protector of Chinese who was informed, had a meeting with the men and they were at work yesterday.”

Pada Khamis 11 Mac 1937, lebih 1,000 orang pekerja ladang (kebanyakannya kaum wanita Tionghua) telah melancarkan mogok di 9 buah ladang getah di Selangor iaitu Ladang Bangi, Connemara, Sungei Rinching, Prang Besar, Sydney, Bukit Tunggu, Balau, Hawthornden, dan Wardieburn dan menyatakan 18 tuntutan mereka terhadap pihak pengurusan ladang-ladang tersebut: “There is general unrest on the rubber estates in Selangor and over 1,000 coolies, all Chinese, are striking on nine estates around Kuala Lumpur and Kajang - on the Bangi, Connemara, Sungei Rinching, Prang Besar, Sydney, Bukit Tunggu, Balau, Hawthornden and Wardieburn estates.”

Di Ladang Wardieburn, telah berlaku sedikit kekecohan. Pada mulanya mereka berunding dengan pihak pengurusan ladang berkenaan mengenai 18 tuntutan mereka itu. Kemudiannya situasi menjadi tegang, dan pihak polis dipanggil ke lokasi. Apabila gambar mereka diambil oleh wartawan akhbar tanpa kebenaran mereka, kekecohan berlaku sehingga filem kamera wartawan tersebut terpaksa dimusnahkan. Keadaan reda menjelang lewat petang, dan tuntutan mereka dipertimbangkan pada keesokan paginya: “The only serious trouble has occurred on Wardieburn Estate. … This morning everyone of them came to the factory where they squatted around but refused to work. They put forward 18 demands. Mr. Linnel, Mr. Grice and Mr. Davis tried to speak to them, but they suddenly became threatening and the police were called in. … About 200 Chinese coolies, a large number of them women, armed with bottles, threatened the manager, Mr. H. L. Linnel, and the Protector of Chinese, Mr. Norman Grice, who were attempting to settle a strike among them. … The Protector for Chinese in Selangor, Mr. Norman Grice, was surrounded by them on his arrival at about 11 a.m. and as the position appeared serious, the Kuala Lumpur police were summoned. … Five lorry loads of armed police under the charge of the Chief Police Officer, Mr. A.H. Dickson, the O.S.P.C., Capt Morrish and Mr. R.O. Davis, O.C.D., left for the estate. … A force of 200 constables with batons and rifles were dispatched under the Chief Police Officer, Mr. A.H. Dickinson, and were stationed outside the factory where the negotiations were being held. The strikers, now numbering about 300, retained their bottles and refused to come to a settlement. … The estate factory, where the trouble was taking place, was surrounded by the police. The Protector of Chinese and Mr. Linnell spoke to the coolies and soon had the situation in hand. An incident took place, however, which nearly had serious consequences, when a group of the strikers surrounded a pressman and a compatriot who were taking photographs, and demanded the camera with threats. … About 300 strikers, most of them women armed with bottles, surrounded him (The Straits Times representative who visited Wardieburn Estate) and demanded the destruction of a camera film on which he had taken strike scenes. They mistook the European reporter for a police officer. When he got into his car 200 people formed a wall around it, preventing it from leaving, while six women tore open the doors and leaped in brandishing bottles. The Police dragged the demonstrators out but the demand for the camera continued in excited voices and upon the advice of the police, the reporter destroyed the film. This prevented further serious incidents. … Police interferred but the men were not satisfied even when the owner of the camera unrolled his film and destroyed it. They only calmed down after he had handed the camera to the police. … A late message from our representative states that things quietened down in the evening and an agreement has been made between the strikers and the management to discuss terms this morning. There are good grounds for believing that Communist agitators are at work behind these strikes.”

Sementara itu, bagi mogok di estet Sungei Rinching, Prang Besar, Connemara, Bangi, Bukit Tunggu, Sydney, Balau, dan Hawthornden, tuntutan mereka dapat diselesaikan lebih awal: “Other estates on which strikes among the workers are reported are Sungei Rinching, Prang Besar, Connemara, Bangi, Bukit Tunggu, Sydney, Balau and Hawthornden estates. In these cases, it is understood, the demands of the men have been very reasonable and an early settlement is expected. To accelerate this, a meeting of the managers of the affected estates was held last night to consider the requests put forward by representatives of the strikers. No disturbances have been reported in these cases.”

Pihak pengurusan ladang telah menangani situasi ini secara kolektif. Ada di kalangan para peladang yang mencadangkan agar ditubuhkan suatu lembaga perantara, yang berperanan mengimbangi di antara harga getah semasa dan gaji pekerja ladang. Namun mereka sepakat menyatakan mogok ini adalah pengaruh gerakan komunis, sempena sambutan Hari Wanita Sedunia pada minggu tersebut. Ini berdasarkan ciri-ciri penyusunan serta tuntutan yang sama di setiap lokasi mogok, serta laporan saksi gerakan tersebut di rumah-rumah kongsi pekerja di 2 buah ladang di sekitar Kuala Lumpur: “More than 1,000 Chinese coolies - many of them women - on nine rubber estates in Selangor are still on strike and planters are suggesting the formation of a wages liaison board. An estate manager with 25 years' experience in Malaya told the Straits Times that such a board should maintain the balance between the price of rubber and estate workers' wages. Managers of estates in the Kajang district are already dealing with the strike situation collectively. The consensus of opinion is that the present labour unrest has been organised by Communistic elements in celebration of International Women's Day, which fell this week. It is reported from two estates near Kuala Lumpur that men were seen cycling to labourers' kongsis and inciting coolie women. Strikes on all estates have been organised in a similar manner; identical lists of 18 demands have been presented to the estate managements.”

Sumber:-

Sumber lain: J. Norman Parmer, 1964: "Chinese Estates Workers' Strikes in Malaya in March 1937", m.s.157-158.

Latar Kejadian

Ketika itu buruh dari negeri Cina diuruskan melalui sistem kontrak. Mereka diikat dengan hutang tambang perjalanan mereka, yang dibayar oleh kontraktor buruh atau “kepala”, dan ditempatkan di rumah kongsi yang dibina berdekatan ladang yang melanggan perkhidmatan kontraktor buruh tersebut. Mereka tidak dianggap pekerja ladang biasa, malah gaji mereka dibayar melalui kontraktor, yang sering melewatkan bayaran, mengambil bahagian yang besar, serta memeras mereka. Kedai-kedai keperluan asas di rumah kongsi, yang diurus oleh kontraktor itu sendiri, menjual barangan dengan harga yang mahal. Mereka juga tidak tertakluk di bawah Kod Buruh, serta tidak dipantau oleh pegawai Jabatan Buruh, sebagaimana buruh-buruh India. Kebajikan mereka hanya dipantau oleh Pegawai Hal-Ehwal Cina (Protector of Chinese) yang dilantik oleh kerajaan. Namun pegawai ini tidak mampu memantaunya dengan baik, oleh kerana keupayaan yang terhad, serta gejala pemerasan yang terlalu berleluasa.

(Sumber gambar-gambar: Hsu Chung-Mao, 26 Jun 2020: |"An album of rare photos: From Chinese coolies to Singaporeans").

Sebelum ini, pekerja ladang tidak membantah atau mogok secara terang-terangan, oleh kerana kedudukan mereka yang rentan dan ketiadaan sebarang saluran pihak berkuasa atau kesatuan sekerja. Mereka membantah secara halus, tersembunyi, dan tanpa perancangan kolektif, contohnya dengan merosakkan premis, pokok getah, atau perkakasan: “Indian and Chinese workers were not always passive or docile, nor did they readily submit to the arbitrary rules of the colonial state or plantation companies. Generally, workers avoided open confrontation with unjust supervisors and voiced dissatisfaction through actions such as destruction of property, rubber trees or equipment – actions requiring little or no planning or collaboration.” (Amarjit Kaur, 2014: |"Plantation Systems, Labour Regimes and the State in Malaysia, 1900–2012" (PDF), m.s.12).

Menjelang tahun 1937, mogok pekerja ladang secara terang-terangan mula berlaku secara berasingan di beberapa ladang di Selangor. Antaranya ialah peristiwa mogok buruh Cina di sebuah ladang di Kajang pada Februari 1937. Tidak lama selepas itu (Mac 1937), Kesatuan Sekerja Pekerja Ladang Getah Selangor (Selangor Rubber Workers' Union) ditubuhkan, dan merancang mogok secara besar-besaran, mulai 7 Mac. Tuntutan utamanya ialah kenaikan kadar gaji dan hak untuk menubuhkan kesatuan sekerja secara sah. Siri mogok ini turut merebak ke negeri Pulau Pinang, Melaka, dan Johor, juga sektor perlombongan bijih timah dan operasi pengangkutan kereta api. Pasukan polis dipanggil bagi meleraikan demonstrasi, dan 2 pekerja mogok ditembak mati. Khidmat rejimen askar Punjab turut digunakan, dan polis membuat penangkapan besar-besaran. Namun mogok berterusan sehingga pertengahan Ogos 1937. Pada akhirnya, antara persetujuan yang dicapai ialah ketetapan kenaikan kadar gaji kepada 75 sen sehari, serta peraturan yang lebih ketat terhadap kontraktor buruh bagi mengekang penindasan mereka. Selain itu, Kod Buruh turut diperluaskan kepada buruh-buruh Cina, dan pemantauan kebajikan mereka dipertingkatkan:-

“The Government had been able to curb the oversupply of Indian coolie labour in the depths of the Great Depression through manipulation of the Immigration Fund. It had no such power over Chinese immigrants, so in 1931 it enacted an Immigration Ordinance to apply to them, and followed it two years later with the Aliens Ordinance of 1933. These ordinances together set quotas and restored the number of Chinese who could arrive as deck passengers. The ordinances applied only to males, and one of their unintended consequences was a significant increase in the female component of the Chinese plantation workforce. It became more settled, and coolies living near the estates began to supply a much greater proportion of the local labour. This had consequences for the authority of the contractors who did not have the same control over locals as over coolies who were recruited in China, and who owed passage money. Local labour reacted more strongly against abuses like short and irregular payment. But that alone cannot explain the increase in militancy after 1936, which culminated in the General Strike among rubber workers in 1937. This was due to the increased demand for labour which came with recovery in 1934 and afterwards, and the tactical exploitation of that bargaining advantage by the Malayan Communist Party. A Communist Party had operated in Malaya in the 1920s, but as a branch of its Chinese parent. The Malayan Communist Party (MCP) was established in 1930 by decision of the Comintern and its chief industrial front, the Malayan General Labourers’ Union, a few days later. Police raids almost wiped it out at birth, but it recovered sufficiently to be able to integrate itself with various ‘red’ and ‘grey’ unions by 1934. These operated mainly in Singapore, but by 1935, the Party organisation was beginning to supply skilled cadres for the organisation of strikes among Chinese workers on rubber plantations. The MCP’s membership was almost entirely Chinese, and at this stage it had neither the means nor the ambition to reach out to Indian plantation coolies.”

“In February 1937, a strike occurred among Chinese workers on a British owned estate in Kajang. The Selangor Rubber Workers’ Union called for a general strike of all rubber workers in the State, and it began on 7 March. The strikers’ main demand was for a hefty increase in wage rates, but they also made a series of other claims, including freedom to operate trade unions legally. The strike spread beyond Selangor onto estates in Penang, Malacca and Johore, and into the colliery that supplied the tin mines and the railways. The police broke up demonstrations, and shot dead two of the strikers. The Government called in a Punjabi regiment, and the police made mass arrests, but the strike continued until mid August. The terms of settlement included a substantial rise in wage rates to 75 cents per day, and stricter rules to control abuses by contractors. The Government agreed to extend the provisions of the Labour Code to cover Chinese workers, and subsequently spent much more time monitoring their operations.”

(Sumber: James Hagan, Andrew Wells @ University of Wollongong, 2005: |"The British and rubber in Malaya, c1890-1940", m.s.6).

Berikut adalah tuntutan-tuntutan yang dinyatakan oleh para peserta mogok di seluruh daerah Ulu Langat, yang kemudiannya dijadikan model bagi gerakan-gerakan di daerah dan negeri lain selepasnya, dengan sedikit perbezaan di antaranya (berjumlah 18-19 tuntutan):-

- Gaji penoreh getah dinaikkan kepada $1 sehari. Gaji pekerja am pula dinaikkan kepada 80 sen sehari, dan waktu kerja dihadkan kepada 8 jam sehari.

- Pengurangan unit tugasan bagi penoreh getah, daripada 300-390 batang pokok, kepada 250 batang untuk torehan “V” dan 300 batang untuk torehan tunggal. Bagi cerun yang curam, perlu pengurangan 50 batang pokok lagi.

- Bayaran getah sekerap sebanyak 3 sen per paun.

- Bayaran 50 sen bagi setiap tugasan menanda kulit getah yang bakal ditoreh.

- Bayaran tambahan $2 sebelum permulaan setiap unit tugasan.

- Bayaran tambahan $2 untuk tugasan membasuh cawan getah.

- Bayaran 50 sen sebulan untuk pisau penoreh getah, yang disediakan oleh penoreh itu sendiri.

- Penguatkuasaan Kod Buruh sebagaimana untuk pekerja ladang India sejak 1909, iaitu penetapan gaji minima, had waktu bekerja, dan piawaian kesihatan. Pekerja harus disediakan perumahan, penjagaan mutu kebersihan, serta bekalan air bersih pada tahap sewajarnya. Khidmat hospital, kakitangan perubatan, serta ubat-ubatan harus diberikan secara percuma.

- Penyediaan seorang amah bagi setiap 4 orang anak, dengan kadar upah $18 sebulan.

- Pembinaan sekolah di dalam ladang, dan tenaga pengajarnya disediakan.

- Pekerja yang jatuh sakit dimasukkan ke wad hospital kelas kedua, dan dibayar separuh gaji.

- Penaiktarafan kediaman para pekerja.

- Bayaran pendahuluan sebanyak $6 pada 15 haribulan setiap bulan, untuk pembelian sayur-sayuran.

- Makluman kadar bayaran gaji diberikan 3 hari sebelum tarikh pembayaran.

- Rehat diberikan sepenuhnya pada hari-hari kelepasan am.

- Pekerja tidak boleh dipecat tanpa alasan yang kukuh.

- Penghapusan hukuman denda terhadap pekerja.

- Pengambilan pekerja baru mestilah dengan persetujuan pekerja sedia ada.

- Pemberian hak kebebasan berpersatuan, berkumpul, bersuara, dan hak penerbitan (Matlamat: penubuhan kesatuan sekerja).

“Strikes first started in the Ulu Langat district of Selangor in early March. During the Great Depression the rubber companies in the district dispensed with the labour contractors and turned the Chinese labourers into direct employees. All other aspects of labour administration on the estates, including wage payment by result and non-enforcement of the provisions of the Labour Code, remained unchanged. Actual labour conditions in the district, therefore, differed very little from the rest of the estates. The labourers demanded daily wages of one dollar, reduction of one task from 300-390 trees to 250 trees for V-cut tapping and 300 trees for single cut tapping, scrap rubber to be paid at 3 cents per pound, 50 cents per task for marking bark, fifty trees per task to be reduced at steep places, $2.00 extra for starting new task, $2.00 extra for washing cups, daily minimum wage of 80 cents and eight hours for general labourers doing miscellaneous work, 50 cents monthly to be paid for tapping knife, which was provided by the labourers themselves. They also demanded the enforcement of the provisions of the Labour Code, amah to be provided by the employers at 18 dollars per month for every four children, schools to be built in the estates and teachers provided, sick labourers to be admitted to second class hospital ward at half pay, labourers' quarters to be improved, advance of $6.00 on the 15th of each month for vegetables, three days' notice before wage settlement, rest on public holidays, no workers to be dismissed on pretext, the abolition of fines and labourers' consent to be obtained for the engagement of new labourers. Lastly, a demand for freedom of association, assembly, speech and publication was included in a list of otherwise entirely economic claims. The demand for freedom of association was related to the intention of the estate labourers to form their own trade union.”

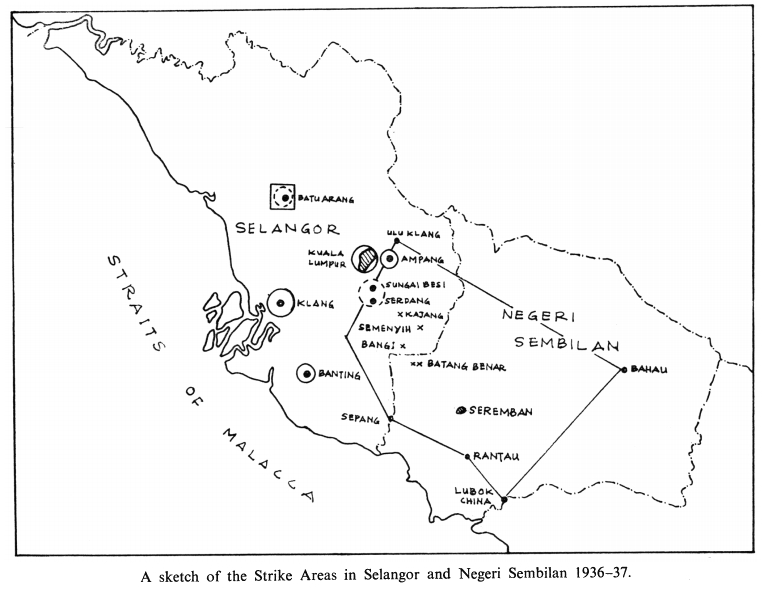

Mogok ini merebak ke seluruh Selangor dan Negri Sembilan. Menjelang 17 Mac 1937, kira-kira 20,000 pekerja Tionghua menyertainya. Jabatan Buruh mendapati kegiatan mogok ini tersusun. Arahan, maklumat, serta komunikasi mengenainya disebarkan menggunakan basikal dan bas ke ladang-ladang, dan senarai tuntutan turut tersiar di akhbar-akhbar vernakular. Penganjurnya berdisiplin tinggi dan berjaya mengawal elemen-elemen tidak diingini ketika mogok berjalan. Walaupun tanpa kesatuan sekerja, mereka maish berupaya untuk tawar-menawar dengan para majikan secara kolektif.

“Strikes spread rapidly from the Ulu Langat district to the whole of Selangor and Negri Sembilan, and by March 17 some 20,000 Chinese estate labourers were estimated to be on strike in the two states. The Labour Department observed that “the strikes were well organized. Bicycles and buses were used to convey instructions and information over a wide area. The organizers maintained a high standard of discipline and managed to restrain their unruly elements almost completely.” Labour organizers and agitators frequented the estates to spread the strikes and to maintain liaison among the strikers. It was largely through the activities of these labour organizers and agitators that the strikers were wielded into one collective force and the strikes on the estates ceased to be sporadic and disconnected. The list of claims raised by the strikers in Ulu Langat became the model on which all subsequent claims were framed, with only minor alterations. The vernacular press, which published the claims in full, played an unconscious but important part in ensuring the regularity of the men's demands. Spokesmen were appointed from among the labourers, and they were available when the need for dialogue and negotiation arose. In spite of the lack of an estate workers' union, the strikers in Selangor and Negri Sembilan entered into collective bargaining with their respective planters' association as one single bargaining unit.”

(Sumber: Tai Yuen, 1973: |"Labour unrest in Malaya, 1934-1941" (PDF), m.s.143-146).

LATAR PERISTIWA: Getah di Malaya

Faktor Kejadian

Faktor 1: Zaman Meleset

Sepanjang zaman meleset tahun 1930-1933, sebagaimana pekerja-pekerja lain, pekerja Tionghua menderita gaji dipotong atau tidak dibayar, diberhentikan kerja, atau dihantar pulang. Kadar gaji mereka jatuh lebih rendah berbanding pekerja India, sehingga banyak ladang mula menggantikan pekerja India dengan pekerja kontrak Tionghua bagi menjimatkan kos. Keadaan kebajikan mereka yang sedia terabai, menjadi semakin buruk. Rumah-rumah kongsi mereka dibiarkan rosak dan tidak terurus. Pihak kontraktor dan pihak pengurus ladang gagal memberi perhatian sewajarnya, disebabkan kekurangan kakitangan dan masalah kewangan yang meruncing. Pegawai Hal-Ehwal Cina pula masih tidak berupaya menangani masalah yang berleluasa ini:-

“…the depression had forced wages down to the bare subsistance level in the rubber, mining and other industries. In fact, Chinese labourers in rubber estates were often paid less than Indian coolies during the depression - a fact that ironically caused a substantial increase in the Chinese estate labour force. Many rubber estates such as those belonging to the Guthrie group had Indians repatriated to India at government expenses and then engaged Chinese. Drastic wage cuts and other difficulties were however, accepted by Chinese workers as inevitable exigencies of the time.”

“One of the iniquities of the contract system was the general neglect of workers' welfare and living conditions. As the contractor engaged the labourers, he was made the employer under the Labour Code. Legally he was obliged to provide certain social amenities to workers such as the provision of proper accommodation, sanitary arrangements and water supplies. In practice these were provided, albeit haphazardly, by the estate, the mine or the factory. During the depression kongsi houses in mines and estates were left to rot and nothing had been done since to repair the revages of those difficult years. In 1938 Blythe reported that accommodation and sanitary arrangement in mines left 'ample room for improvement'. In most rubber estates the kongsi houses were in a most dilapidated state of conditions. In the Tanah Merah Estate in Negri Sembilan, an extremely bad example, the latrine of the kongsi house had collapsed and left unrepaired. The 130 inhabitants slept in one corner of the kongsi house because the roof leaked. Conditions elsewhere were superior but filth surrounded the kongsi houses in a large number of the estates. In one Negri Sembilan estate the coolie houses were 'well constructed and airy' but 'were simply hemmed in with filth and dirt and swarms of flies pounced on the rice which the tappers were eating.' But contractors cared little about living conditions in the estates or the mines, so long as these did not depress their earnings. The attitudes of managers were no better, preoccupied as they were in the case of rubber estates with the living conditions of Indian labourers. Their indifference was explained away on the grounds that they were unable to converse in Chinese or that Chinese resented interference into their affairs by outsiders. Nor did British officials act to improve the situation. The Chinese labourer was left alone, Governor Thomas explained, because he 'has always been able to take care of himself. When he has been dissatisfied with the treatment he has received, whether direct from his employer or at the hands of a contractor, he has gone to his employer or to the [Chinese] Protectorate and got his complaint adjusted or has indulged in a peaceful strike'. Little wonder that the Chinese Protectorate was neither sufficiently interested nor equipped with enough men to closely supervise and inspect the contract system. In short the workers were left in benign neglect - and in deep resentment- during the immediate post-depression years.”

“The contractor was, of course, no longer as powerful in the employment system as previously. His financial hold on labour had been drastically impaired as the recruits from the lodging houses no longer commenced work in a state of indebtedness. Still he was the stronger of the two parties and continued, albeit less blatantly, to ex- ploit labour. In certain ways the depression had had the effect of strengthening his authority over workers. The austerity drive then led to a drastic reduction in European staffs engaged in mines and estates. For instance, the 3800-acre Temiang Estate in Negri Sembilan cut its European staff from six officers to two. It was not common therefore, for a manager to take charge of more than two or three estates after the depression. Supervision of estates became more difficult and lax, and the manager was thrown back into greater dependence on the contractor. He found it harder to try to exercise control over the size of the task assigned to workers usually he did not even know what wage rate was paid the workers because the contractor kept his account books in Chinese. It was therefore, not uncommon for the contractor to underpay the labourers. The lack of supervision tended also to encourage another fairly widely practised abuse in rubber estates. Under the contract system the manager first paid the contractor who in turn remunerated the labourers. Usually labourers were kept informed of the dates of such payment by a notice posted in the estate. During the early post-depression years the hard-pressed and over-worked manager frequently overlooked this. Many contractors conveniently forgot to pay the labourers and after a few months absconded and disappeared. In such cases the victims often appealed to the Chinese Protectorate in vain.”

“It was common practice under the contract system for contractors to supply labourers with food, sundries and other goods. To continue in this business during the slump many contractors were compelled to rely on loans from shopkeepers in the nearby towns. The former in turn agreed to buy goods only from the particular shopkeepers con- cerned and to sell them to their labourers at exorbitant prices. In a great many estates, especially those in remote areas, labourers usually shopped in the contractor's kongsi house. Convenience was only partly responsible for this. Frequently workers did this to avoid offending the contractor and being saddled with difficult tasks of work. Hence, during the immediate post-slump days a large proportion of the labourers' earnings in many estates was re-circled to the contractor through the village shop.”

(Sumber: Yeo Kim Wah, 1976: |"The Communist Challenge In The Malayan Labour Scene, September 1936-March 1937", m.s.7-8, 10).

Sementara itu, pihak kerajaan telah menggubal beberapa ordinan bagi menetapkan kuota imigrasi buruh dari Cina, iaitu Immigration Ordinance (1931), diikuti Aliens Ordinance (1933). Namun, ordinan-ordinan ini hanya menyebut buruh lelaki sahaja, dan tidak menyatakan apa-apa tentang buruh wanita. Tambahan pula, harga tambang perjalanan dari negeri Cina ke Malaya jatuh merudum. Faktor-faktor ini menyebabkan pertambahan pekerja wanita Tionghua secara drastik. Mereka bergabung dengan pekerja wanita sedia ada di Malaya yang telah pun bebas dari ikatan hutang dengan kontraktor mereka, dan sebahagiannya telah berkeluarga serta berpendidikan. Faktor-faktor ini menyebabkan mereka ini lebih sensitif terhadap pelanggaran hak-hak mereka, contohnya pembayaran gaji yang tidak cukup atau lewat.

Pada tahun 1934, keadaan ekonomi industri kian pulih. Harga getah melonjak sebanyak 250 peratus. Para pemilik ladang menyalurkan keuntungan yang diperolehi untuk memulihkan keadaan mereka. Namun kadar gaji dan kebajikan pekerja masih tidak berubah. Sementara itu, kesedaran kelas pekerja semakin meluas di kalangan para pekerja Tionghua, melalui bahan-bahan bacaan gerakan pekerja sedunia yang disiarkan dalam akhbar vernakular Cina. Mogok mula berlaku pada tahun tersebut. Menjelang tahun 1936, kegiatan mereka menjadi semakin meluas dan radikal, kesan pengaruh para aktivis Parti Komunis Malaya, serta kesatuan sekerjanya Malayan General Labour Union (MGLU), yang giat menyusun aktiviti mogok di kalangan buruh Tionghua di ladang-ladang getah Malaya ketika itu:-

“Labour unrest developed from a limited scale in 1934-35 to an unprecedented dimension which encompassed all grades of workers in a wide range of industries throughout Malaya in 1936. Improving economic conditions without a corresponding improvement of wages and working conditions no doubt contributed to the rising incidence of labour unrest. Only a small section of the labour force, namely, the Chinese craftsmen, had improved their position through collective bargaining in 1934-35, but the overwhelming majority still remained in depression conditions. The overriding issue, therefore, was still the recovery of the pre-depression wages rates, but a host of other issues, including hours, the contract lab our system, etc., also came to the fore. Experiences in the previous two years had underlined the importance of organisation in advancing the interests of labour, and therefore a determined effort at unionisation was made as broad sections of Malayan labour pressed for their claims. … The centre of labour unrest shifted from Singapore to the Malayan mainland. The big strikes of the Chinese rubber tappers in Selangor and Negri Sembilan were launched in protest against low wages, the abuses of the contract labour system and unsatisfactory working conditions. The earnings of Chinese estate labourers in the two states remained at 60-65 cents per day at the beginning of the year, although rubber prices, profits of rubber companies, and the cost of living all registered increase. Slight increase of Chinese wages was granted in Perak and Kelantan from January 1, 1937, but the rubber planters were reluctant to extend similar wage increase to other Malay states. As a whole earnings of Chinese estate labourers still lagged a far way behind the pre-depression level. Most of the Chinese labourers on European estates were employed under contractors, whose irregular practices became all the more oppressive when wages remained stagnant. Housing conditions were poor; workers were crowded into ill-ventilated kongsi houses with mud floors; medical attention, maternity benefits, schools and nurseries for labourers' children were non-existent. Unsatisfactory working conditions were partly the result of the non-enforcement of the provisions of the Labour Code among the Chinese labourers.” (Tai Yuen, 1973: |"Labour unrest in Malaya, 1934-1941" (PDF), m.s.110, 151-152).

“The above developments were brought to a head, so to speak, by the Malayan depression, 1930 - 33. For four harrowing years Chinese (as well as other) workers suffered drastic wage slashings and under-or unemployment. The more unfortunates were repatriated to China. The immigration restriction law of 1928, a result of the Kreta Ayer riots in 1927 and aimed at preventing political undesirables from landing in Malaya, was implemented in 1930 to ease the situation. But convinced that the future growth of the Malayan economy would be much slower, British officials called for more stringent control. The existence of a sizeable pool of local labour was considered sufficient to overcome any future drastic labour shortages in the country. In 1933 the government accordingly enacted the Aliens Ordinance which set an annual quota for Chinese immigration to Malaya. No longer could employers continue to keep wages down by increasing the volume of Chinese immigration to the country during booms. The result was a vast increase in the bargaining power and class consciousness of Chinese (and other) labour - a development further enhanced by India's banning of unskilled Indian labour immigration to Malaya in 1938. It should also be noted that the Aliens Ordinance accelerated the immigration of Chinese women to Malaya. Not only was there no quota set against female immigration but the ticket fares were substantially cheaper. The growing numbers of Chinese women in turn encouraged the expansion of the permanent pool of local labour. It also raised new problems such as the payment of maternity benefits - an issue during the strikes in 1936 - 7. The position in Malaya in 1935 was therefore, that bachelor labour had to a significant extent been replaced by family units living either in kongsis or on their own and that a stringently controlled Chinese labour market had given way to a virtually free one.”

“By the mid- 1930s employers and contractors had to face a more class-concious and knowledgeable Chinese labour force. … To a crucial extent this may be traced to the spread of Chinese education in Malaya and China, which had produced a sizeable pool of educated Chinese workers with a deeper knowledge of Malayan and world conditions. They read publications by the 'Proletariat Literature Movement' in China, 1928- 1931 . Many 'Proletariat' books came by way of Shanghai to Malaya and similar articles were reprinted in the local Chinese newspapers. Influenced by Russian communist ideas, these publications discussed the oppression of the working class and the evils of capitalism. They helped stir labour conciousness and induced educated Chinese to adopt a less accommodating attitude towards the 'capitalists'. Through the newspapers and other publications educated Chinese also learned about labour struggles and the growing labour movements in Europe. Great indeed were their impressions when they read about workers scoring victory after victory in strikes that rocked European countries in 1936. This, they felt, could be repeated in Malaya in view of the labour shortage that had already resulted from the operation of the Aliens Ordinance. Indeed, this was the message pounded home by labour leaders and communist agitators in a great many of the Malayan strikes in 1936 and 1937. The outlook and much of the knowledge of educated Chinese invariably spread to the general Chinese labour force through the mass media and ease in communication. The daily Chinese newspaper, for instance, was frequently found in the kongsi house and there on many an evening a better-educated man would expound on what he read therein to his fellow workers sitting around him. On the other hand, the ubiquitous, usually cheap Japanese-made bicycle had enabled workers to conduct and sustain continuous interactions with their fellows in the neighbourhood. By the mid-1930s Chinese workers had come to ignore with equanimity warnings or threats by employers or government officials that 'unreasonable' pay demands would lead either to their replacement by Indian coolies or to a flood of new immigrants who would depress the wage level.”

“The economic gloom started to lift in 1934. The prices of Malayan exports such as tin and rubber rose sharply - in the case of rubber to one shilling per pound in 1936-1937, an increase of 250 per cent. But while the cost of living had also risen, the expected wage bonanza was nowhere to be seen. Some workers were given inadequate concessions such as the rubber tappers in Kajang in Selangor who had their daily wage rate pushed up from forty-seven to sixty or sixty-five cents in 1936, or the Singapore building workers who enjoyed a twenty-five per cent increase in 1934. Others like pineapple factory and mining workers were ignored. Employers were enjoying attractive profits for the first time in years and were preoccupied with issues other than wage increase such as the rehabilitation of their businesses. To borrow the Governor's phrase, 'the slump mentality' had lasted too long among them. Conscious of their enhanced bargaining power and irked by the slump wages they laboured under, Chinese workers began to strike for better deals on an unprecendented scale. The strike movement commenced with skilled workers such as carpenters and printers in 1934, climaxed with the rubber tappers and coal mine coolies in March 1937, and spilled beyond thereafter. As the Sin Chew Jit Poh rightly asserted, the immediate and most important cause of the strikes was employers' failure to pay workers 'a proper wage'.”

(Sumber: Yeo Kim Wah, 1976: |"The Communist Challenge In The Malayan Labour Scene, September 1936-March 1937", m.s.3-4, 9).

“'Samsui' women working at a construction yard, 1938-1938. Collection of National Museum of Singapore.”

“Two developments took place in 1933 which saw Chinese female immigrants coming to Singapore. Firstly, the British colonial authorities started limiting the number of male immigrants allowed into Singapore. Secondly, the impact of the Great Depression was felt globally. These events contributed to a wave of about 200,000 Chinese female immigrants to arrive in Singapore between 1934 and 1938. Women from southern China travelled by boats to Nanyang, or the Southern Seas. Just like the men had done a century before, these women were in search of work and a new life. Many of them chose to “sor hei” – ceremonially combing their hair into buns to set themselves apart. Some even took a vow of celibacy. They formed sisterhoods, or surrogate families loosely based on clan association structure. Those from Shan Shui, a district in the Canton province, became fearless builders in the construction industry. Called the hong tou jin (or samsui women), they were easily distinguished by their red head scarves, black samfu and sandals fashioned from old rubber tyres. Those from Shunde district became majie, loyal and reliable nannies who brought up a whole generation of children across Malaya.”

(Sumber gambar dan petikan: National Heritage Board, Singapore: |"Destination - Nanyang").

LATAR PERISTIWA: Getah di Malaya

Faktor 2: Peranan Komunis

Di dalam persidangan Parti Komunis Malaya pada 1-8 September 1936, suatu perancangan strategik telah dibentangkan, di mana aktivis-aktivis parti akan bekerjasama dengan kesatuan-kesatuan sekerja pelbagai industri bagi merancang siri aktiviti pembelaan hak dan kebajikan pekerja yang lebih besar dan sistematik, sebagai persediaan kepada gerakan revolusi menentang imperialisme British: Pada bulan Mac 1937, mereka berjaya mendapat kerjasama dari beberapa kesatuan sekerja, antaranya Coal Workers' Union di Batu Arang, the Pineapple Cutters' Benevolent Association di Klang dan the Rubber Workers' Union di Kajang: “The party split was resolved in a conference of the Fifth Enlarged Central Executive Committee held in Muar, Johore, from 1st to 8th September 1936. At this meeting the fourteen representatives from Singapore, Johore, Penang and Selangor adopted a policy on September 3rd entitled 'To Struggle for the Establishment, Consolidation and Expansion of the Anti-Imperialist United Front.' … This front was intended 'to give forceful effect to the workers' movement for high wages and better working conditions.' Communists were urged to exploit the labour situation because workers were suffering from 'low wages, long hours and abuses by contractors and sub-contractors' at a time of returning prosperity in Malaya. In doing so, they should also merge workers' desire for better economic welfare with the MCP anti-colonial struggle. Communists were directed 'to push on the anti-capitalist labour movement and to develop it from an economic struggle into a revolutionary movement against Imperialism'. To attain the above goals, communists were told to penetrate existing labour organisations and especially, to concentrate on building up 'Red' (Communist) and 'Grey' (Communist- dominated) unions 'on a factory, mine, plantation and wharf basis'. Special attention was to be devoted to 'railway shops and centres such as Sentul and Singapore, the most important tin mines and smelters, rubber factories and plantations such as the region of Kuala Lumpur, Ipoh and Seremban, the shipping lines and wharves in Singapore, Penang and Malacca, and in the Singapore Naval Base'. Under the new policy each communist-controlled union would seek registration under the Societies Ordinance. The consequent legal labour movement would then come under the MGLU directed by party itself. … Led by Chiù Tong, the MGLU intensified its policy of forming 'red' worker cells in the pineapple, building, match-making, rubber-goods and other factories in Selangor. The most successful unions formed by March 1937 were the Coal Workers' Union in the Malayan Collieries at Batu Arang, the Pineapple Cutters' Benevolent Association at Klang and the Rubber Workers' Union at Kajang. … Most of the above unions, as discussed later, played a vital part in the strikes that occurred between September 1936 and March 1937.” (Yeo Kim Wah, 1976: |"The Communist Challenge In The Malayan Labour Scene, September 1936-March 1937", m.s.5-7).

Pada tahun 1937, wakil aktivis komunis, Chiu Tong, menubuhkan Jawatankuasa Mogok Kajang, dengan 12 orang dari kalangan aktivis Parti Komunis dan Kesatuan Sekerja General Labour Union (GLU). Mereka digerakkan di kalangan pekerja untuk merancang mogok. Pada 7 Mac 1937, 19 tuntutan telah dihantar kepada para majikan di Selangor dan Negri Sembilan, antaranya Bangi Estate, Connemara Estate, dan Sungei Rinching Estate. Kesemua tuntutan tersebut langsung tidak dipertimbangkan oleh pihak majikan, yang menganggapnya luar biasa dan keterlaluan. Kesatuan Sekerja Pekerja Getah (Rubber Workers Union - RWU) terus ditubuhkan di Selangor dan Negri Sembilan. Pada keesokannya (8 Mac 1937), mereka dikatakan menyeru pekerja wanita di Wardieburn Estate dan kilang Shum Yuk Leung untuk tidak bekerja bagi menyambut Hari Wanita Sedunia. Bendera merah dinaikkan di Wardieburn Estate. Maka pada hari tersebut, pekerja wanita di beberapa tempat memutuskan untuk tidak bekerja bagi menyambut Hari Wanita Sedunia. Tindakan ini antara lain mengakibatkan pekerja wanita yang terlibat di ladang Bangi telah dibuang kerja oleh majikan. Rentetan peristiwa ini telah mencetus gerakan mogok besar-besaran 2 hari selepasnya (11 Mac 1937), di mana pekerja wanita di ladang-ladang lain turut mogok. Secara keseluruhannya, siri mogok ini berjaya diselesaikan di peringkat pengurusan ladang, tanpa campurtangan kerajaan:-

“The more skilful Chiu Tong then took over and manipulated the situation more subtly and cautiously. He began by grouping the leading MCP (Malayan Communist Party) and GLU (General Labour Union) activists into a twelve-men committee subsequently known as the Kajang Strike Committee. These activists then scattered among the workers to incite and marshall support for a general work stoppage. No mention was made about the Rubber Workers' Union (RWU) they intended to form lest this scared away tappers. By early March the ground had been sufficiently prepared and Chiu Tong issued the order to commence action. A list of nineteen demands purportedly drafted by Lee, Chairman of the Northern Central, and subsequently submitted to other employers in Selangor and Negri Sembilan, was presented to the Bangi Estate in Bangi, the Connemara Estate in Semenyih and the Sungei Rinching Estate in Kajang on March 7th. Employers' refusal to even consider the demands sparked off the strike. Thereupon Chiu Tong announced the formation of the RWU of Selangor and Negri Sembilan and a general membership drive began. On March 8th Lee (or Ngaw), a communist propagandist, purportedly instigated women workers in Wardieburn Estate and Shum Yuk Leung Factory to cease work in order to celebrate the Russian-sponsored International Women's Day. To mark the occasion a woman raised a Red Flag in Wardieburn Estate. The next day the largely female labour force downed tools in Wardieburn and Hawthornden Estates near Ulu Klang. Two days later the Kajang Strike Commitee despatched Yeong Mah Kee and two other communist agents to foment unrest in Negri Sembilan. On November 12th tappers in Batang Benar were induced to submit demands and when employers proved intransigent, strikes erupted. Partly carried by its own impetus, the strike spread to many other estates in Selangor and Negri Sembilan. During this time the orderly nature of the strikes and workers' readiness to negotiate offered no cause whatsoever for government intervention - an eventuality already desired by several employers and police officers.”

Sebagaimana dinyatakan sebelum ini, reaksi awal pihak pengurusan yang tidak mempertimbangkan langsung 19 tuntutan itu, malah mengugut untuk menukarkan pekerja Cina dengan pekerja Jawa dan India, merupakan faktor utama tercetusnya mogok besar-besaran ini. Selama ini mereka telah terlalu biasa dengan pekerja India yang lebih mudah dikawal, dan persepsi mereka terhadap pekerja Cina sebagai “pendatang” ke “negeri mereka”, yang wajar menurut saja kehendak mereka tanpa bantahan yang tersusun: “The more hostile reaction of employers to the estate strike was conditioned by their being accustomed to nearly thirty years of treating with a docile Indian labour force and of determining wage rates and working conditions above the head of estate coolies. Over the years they had acquired an attitude summed up in a Malayan Tribune article (21.9.1936) on the labour situation which read: 'it should be made clear that the authorities will not tolerate anything that savours of organised agitation. This is British territory, and the men concerned in the strike are aliens. They came here because the inducements held out appeared good to them, and once here they have to coduct themselves with the circumspection expected of any alien in a foreign country'. In indignant surprise, therefore, the irate managers of the Bangi, Connemara and Sungei Rinching Estates on March 7th and that of Batang Benar estate on March 11th all flatly refused to consider the strikers' demands. In Bangi and Batang Benar, the managers even threatened to replace the strikers with Javanese and Indian coolies respectively. Such intransigent attitude only helped to escalate the strike in the two Malay states.”

Jabatan Hal Ehwal Cina turut menyebelahi pihak pekerja, walaupun mereka sendiri turut dikecam oleh pihak pekerja. Ini kerana mereka turut bersetuju dengan sebahagian tuntutan mogok yang berkaitan kadar gaji dan kebajikan pekerja, dan turut mengecam kesombongan sebahagian para majikan yang tidak mahu mempertimbangkannya. “In brief, little prospects existed for a peaceful settlement of the March unrest. Nonetheless, Chinese Protectorate officers persisted in that direction to the very end. To them they were merely performing their role of protecting Chinese welfare, as they believed that the March strike was motivated basically by genuine economic grievances. They tended to be sceptical of the view that it was communist controlled and directed, an understandable standpoint as no concrete proof of this was forthcoming until late March. Overall, the sympathy of Chinese Protectorate officers lay with the strikers, and on occasions the Chinese Protector, N. Grice, sided with workers. He was caustic towards the instransigence and arrogance of particular employers. When labour demands were brushed aside at Connemara Estate on March 7th the Chinese Protector felt that 'some of the demands are unreasonable but the manager is still more unreasonable in not even attempting to negotiate'. In another report on the working conditons of tappers, he stressed 'that the estates had exhibited less than ordinary consideration for the comfort of the labourers'. Throughout the period, the Chinese Protector, to the surprise of the Selangor Resident, was good-humoured and indulgent towards the strikers even though he suffered considerable harrassment and at times had to be freed by the police from tight corners. The views of the government until late March were more akin to those of the Chinese Protectorate than of the Police Department. After the initial shock, the government became critical of employers, both for their bad faith in not observing fully the agreements contracted since November 1936 and for their general refusal to consider labour demands in March 1937. Besides, Thomas conceded that estate tappers did not enjoy 'a proper wage'.”

Demikian juga pihak kerajaan, yang terus berusaha mendapatkan kerjasama pihak majikan untuk mempertimbangkan tuntutan-tuntutan mogok, dan mencadangkan sebarang tawaran balas kepada pihak pekerja: “The views of the government until late March were more akin to those of the Chinese Protectorate than of the Police Department. After the initial shock, the government became critical of employers, both for their bad faith in not observing fully the agreements contracted since November 1936 and for their general refusal to consider labour demands in March 1937. Besides, Thomas conceded that estate tappers did not enjoy 'a proper wage'. But confronted with such large-scale strikes for the first time, the government was rather muddled on how to act, especially when it did not fully understand labour grievances nor know the possible concessions forthcoming from employers. British officials endeavoured to persuade planters and their associations to spell out their possible offers but in vain. Much to its annoyance, the government found employers' attitude a hindrance to the mediatory role it intended to play. In line with its laissez-faire policy, the government concentrated on creating the conditions conducive to a peaceful settlement and preventing any breaches of the peace. It would neither compel employers to make concessions nor press workers to resume work without a proper settlement. In this British officials were until late March encouraged by the optimistic situational reports sent by the official negotiators.”

(Sumber: Yeo Kim Wah, 1976: |"THE COMMUNIST CHALLENGE IN THE MALAYAN LABOUR SCENE, SEPTEMBER 1936—MARCH 1937", m.s. 11, 17, 30, 33-34).

Faktor 3: Peranan Wanita

Peranan wanita amat ketara dalam siri mogok besar-besaran ini. Mereka mengetuai mogok-mogok dari Ulu Langat hingga ke Negri Sembilan. Mogok di utara Kuala Lumpur pimpinan mereka menjadi agak agresif, sebagaimana dalam liputan akhbar di atas. Di Mantin, separuh peserta mogok yang duduk berdemonstrasi di tengah Jalan Mantin adalah kaum wanita. Faktornya ialah sebahagian daripada senarai tuntutan adalah hak-hak pekerja wanita yang belum pernah diperolehi, serta jumlah mereka yang semakin bertambah sejak 1933: “Women labourers played a very conspicuous part in the big strikes. The Labour Department observed that “the strike spread (from Ulu Langat) to Negri Sembilan and also to the north of Kuala Lumpur. Women took a leading part in it and in north of Kuala Lumpur were very aggressive. Among the labourers who staged a sit-down on the Mantin Road when their procession had been stopped by the police, half of them were women. They had cause to be aggressive because they were fighting for the rights of female labourers which they had never enjoyed besides other claims. The large influx of Chinese women immigrants since 1933 had therefore as one of its results the growing importance of women labourers in industrial disputes in the rubber industry as well as in a number of other industries.” (Tai Yuen, 1973: |"Labour unrest in Malaya, 1934-1941" (PDF), m.s.148).

Butiran kejadian mogok di Selangor, menurut sudut pandang pekerja wanita: “Kemaraan kesatuan buruh-buruh wanita semakin memuncak apabila lima daripada ladang getah berhampiran, iaitu Ladang Getah Connemara, Ladang Getah Sungei Rinching dan Ladang Getah Bangi turut melancarkan rusuhan dan mogok secara serentak. Mogok ini dilancarkan apabila pihak majikan apabila pihak pengurusan ladang getah membuang pekerja wanita ladang getah Bangi apabila pekerja-pekerja ini menghentikan kerja buat sementara bagi bagi menyambut Hari Wanita Antarabangsa pada 8 Mei 1937. Pihak majikan bertindak membuang buruh-buruh wanita ini kerana menganggap mereka merupakan agen subversif Komunis. Kerja-kerja buruh ini telah digantikan dengan buruh-buruh murah dari Jawa (SSG 194/1937: Strike on Connemara Estate). Tindakan pihak pengurusan membuang buruh-buruh wanita yang terlibat telah menyebabkan kemarahan rakan-rakan mereka yang lain. Keputusan ini juga menyebabkan mereka melancarkan mogok di lima buah ladang getah yang terlibat secara serentak.” (|Ruhana Padzil, 2017: "Perjuangan wanita dalam aktivisme sosial dan nasionalisme di Tanah Melayu, 1929-1957", m.s.244-248)

Sumber lain: “Later, the police were incensed by events on the Wardieburn Estate in Ulu Klang, where female tappers flew a red flag and stopped work to observe International Women’s Day; 'one of the days decreed for celebration by the Communist Party of Russia,' fumed Commissioner Sansom. At the same time, he claimed that the strikers had lodged 'exorbitant wage demands' and other 'supplementary and unreasonable demands.' These included the provision of childcare for children under the age of five, schools for the coolies’ children, and 'no dismissals or fines without cause and new labourers to be introduced by the present labour force.' In response, the coolie lines on the nearby Hawthornden Estate were raided and the strike leaders dragged off. When the workers held a protest meeting on the lines, the police and soldiers of the Punjabi Rifles attacked with force. Sansom’s report read, 'For three weeks this unruly gathering had been a law unto itself, definitely anti-European and defiant.' This strike wave was later crushed by the state authorities.” (John Tully, 2011: "The Devils Milk: A Social History of Rubber", |Chapter 16)

Peristiwa Seterusnya

Berikutan beberapa peristiwa serta kekecohan lain selepas itu (rujuk urutan peristiwa di bawah), siri mogok dan demonstrasi ini kemudiannya merebak ke seluruh ladang-ladang di Selatan Selangor dan Negeri Sembilan, melibatkan lebih 30,000 pekerja Tionghua. Sekitar waktu yang sama juga (24-27 Mac), mogok turut dilancarkan di lombong arang batu Batu Arang, yang berakhir dengan serbuan pihak berkuasa. Akhirnya pada 28 Mac 1937, persetujuan dicapai di antara Persatuan Peladang Negri Sembilan dan wakil pekerja di sana, diikuti para perwakilan Selangor di Kajang, 3 hari kemudian (31 Mac 1937). Sebahagian daripada tuntutan-tuntutan pihak pekerja telah dapat dipenuhi oleh para majikan.

Urutan Peristiwa

1937-03-12: Pihak majikan mengakui bahawa pekerja dibayar gaji yang rendah, dan bersetuju menaikkan gaji harian daripada 60-65 sen kepada 75 sen, dengan syarat pekerja yang mogok kembali bekerja terlebih dahulu: “After the initial reaction, employers conceded that tappers were underpaid and were willing to increase the daily wage rate from sixty or sixty-five cents to seventy- five cents provided work was first resumed unconditionally. Otherwise, employers felt that any concessions to the workers would only cause a loss of face or teach the coolies the power of the strike weapon. This decision was conveyed to a meeting between the government and the United Planters' Association of Malaya (UP AM) representing employers on March 12th.”

1937-03-14: Tangkapan aktivis: 13 aktivis komunis ditangkap di Jalan Cheras, Kuala Lumpur, setelah mereka menahan seorang penyiasat polis. Setelah Jawatankuasa Mogok Kajang dan Kesatuan Sekerja Pekerja Getah (yang ketika itu berada di Sungai Ramal) menerima berita ini, golongan komunis bertindakbalas dengan berarak ke Kuala Lumpur dan menuntut pembebasan aktivis-aktivis tersebut. Kekecohan berlaku dan polis bertindak meleraikan dan menangkap 110 orang demonstran: “The second stage of the state unrest commenced on March 14th with an ugly incident near Kuala Lumpur. That day a detective on a fact-finding mission was spotted by a group of truculent agitators and was detained. A police party from Kuala Lumpur rescued him at Cheras Road and arrested many 'agitators' including thirteen propaganda corp members. News of this soon travelled to the Kajang Strike Committee then inaugurating the RWU at a mass rally at Sungei Ramai in Kajang. … On learning about the Cheras Road fracas therefore, communist agitators hastily rounded up members of the propaganda and militant corps. A few hundred people then started marching to Kuala Lumpur with a view to taking 'the Protector of Chinese to court to address the court on their behalf' and force the release of the thirteen detained propaganda corp members. On the way in Bolton Estate at Cheras Road the mob spotted four detectives who were immediately set upon. The detectives opened five thrice, hitting a leading agitator (Chen Keow) on the stomach and wounding two others. They then ran for their life with a 700-strong mob close at heels. A police party arrived in the nick of time, scattered the mob with batons and detained 110 demonstrators.”

1937-03-18: Tuntutan pembebasan: Jawatankuasa Mogok Kajang, bersama beberapa kesatuan sekerja lain, terus menuntut pembebasan 13 orang aktivis, sebelum bersetuju ke meja perundingan dengan Jabatan Buruh dan Jabatan Hal-Ehwal Cina: “Police action shook the strikers into a better frame of mind for opening negotiation. On March 18th labour representatives met Labour Department and Chinese Protectorate officers as well as the Chinese Consul at the Chinese Miners' Club. The meeting proved fruitless as the Kajang Strike Committee absolutely refused to participate. Instead, around March 18th communist agitators, ably led by Chiù Tong, injected a political element into the dispute by making the unconditional release of the thirteen detained propaganda corp members a precondition to negotiation. This demand was voiced by estate labourers in Selangor and Negri Sembilan as well as by pineapple cutters, rubber factory hands, matchmakers and other workers in Klang.”

1937-03-22: Demonstrasi besar-besaran: Kerajaan enggan membebaskan tahanan tersebut, lalu pihak jawatankuasa mogok melancarkan demonstrasi aman. Demonstran di Klang, Kajang, dan Ulu Langat bergerak ke Kuala Lumpur, manakala demonstran di Mantin, Rantau, dan Labu bergerak ke Seremban. Mereka membawa bendera besar yang tertulis 19 tuntutan sebelum ini dan tuntutan pembebasan tahanan. Pihak polis berjaya meleraikan semuanya kecuali 1,200 orang demonstran dari Klang yang mengepung balai polis di Kuala Lumpur selama 3 jam. Secara keseluruhannya, 10,000 - 20,000 pekerja ladang di Kajang, Ulu Langat, Sepang, Mantin, Labu, Bahau, Lubok China and Tampin telah mogok: “As the government would not concede to this demand, a deadlock emerged. The strike movement had become partly political in nature. The campaign for the release of the thirteen detainees and the acceptance of the nineteen strike demands reached a crescendo on March 22nd. That day mass demonstrations were held in Klang, Kajang and Ulu Langat and the participants were told to march and converge at Kuala Lumpur. But the few hundred demonstrators in Ulu Langat and Kajang managed only to disrupt traffic. The 1200-strong demonstrators in Klang, ably led by two leading Selangor communists, Boh Chin and Ah Kang, surrounded the police station and in effect, took over the town for three hours. In Negri Sembilan firm police action prevented demonstrators in Mantin, Rantau and Labu from marching to Seremban. In all these marches, demonstrators carried huge flags on which were written the nineteen demands and the call for the release of detainees. All were peaceful affairs, although government officials feared outbreak of riots and violence especially in Klang. As far as this paper is concerned, the estate unrest had reached its maximum scope by March 22nd. when it embraced Kajang and Ulu Langat in Southern Selangor, Sepang, Mantin, Labu, Bahau, Lubok China and Tampin in Negri Sembilan. Altogether between 10,000 and 20,000 estate workers in the above areas were on strike. The regional character of the estate unrest was not intentional as the Kajang Strike Committee's aim was to mount a general stoppage stretching from Selangor to Singapore.”

1937-03-24: Mogok di Batu Arang: Dirancang rapi oleh wakil Parti Komunis Malaya bersama Kesatuan Sekerja Lombong Batu Arang sejak Februari 1937 lagi, sebelum gerakan henti kerja dilancarkan pada 24 Mac, melibatkan hampir keseluruhan 5,000 orang pekerjanya. Mereka membuat 23 tuntutan, antaranya kenaikan gaji sebanyak 50%, pembuangan beberapa kontraktor, dan pembebasan 13 orang aktivis tempohari. Keadaan berlarutan sehingga 27 Mac, dan terdapat kemungkinan merebak ke lombong-lombong lain di sekitar Lembah Kinta dan Sungai Besi. Pihak kerajaan menyedari tindakan tuntas perlu diambil: “After the monster demonstrations on March 22nd Chiù Tong and Chan Han decided to open another front in the Malayan Collieries at Batu Arang, the most vulnerable point in the country's economy. Upon the Malayan Collieries, the only coal mine in Malaya, depended the daily supply of 450 tons of coal to the Railway system, 200 tons to the Bangsar Power Station in Selangor, 500 tons to the Perak River Hydro-Electric Company, 700 tons to the tin dredges, and 150 tons to other consumers. Any strike of some duration in the Collieries would have paralysed the transport, electricity, mining and industrial sectors of the economy. With this in mind, the MCP hoped to compel the government and the employers not only to accept labour demands lock, stock and barrel but also to alter British labour policy. Hitherto, the British had meticulously screened and firmly rejected all applications for the registration of communist or communist-dominated unions under the Societies Ordinance. As illegal organisations, these unions were greatly hindered in their operation. Through the Batu Arang strike, the MCP sought to force the authorities to register the RWU, thereby hopefully paving the way for the recognition of other 'Red' and 'Grey' unions. Ultimately, the MGLU would bring all the unions under the fold of a vocational united front. The fate of the entire strike movement in Selangor and Negri Sembilan therefore depended on the outcome of the Batu Arang stoppage. Not surprisingly this second incident was staged with great care and precision. Through the Coal Workers' Union, Chan Han had been actively preparing the ground since February 1937. His task was eased by widespread labour discontent in the Collieries. Coal miners became restive as they saw the concessions gained in November 1936 rapidly eroded by the rising cost of living, and felt insulted by a five per cent wage increase in March which may, in fact, be considered niggardly in view of the 12 ' per cent dividends and bonus shares at par issued by the company in 1936. At the break of dawn on March 24th the CWU struck. Truculent coolies in groups of fifty and 'carrying pick-handles and hammers' toured the mine to announce the cessation of work. Threatened, Tamil mandores called out their Indian labourers. In no time a general strike had occurred involving almost all the 5,000 workers. A list of twenty-three demands allegedly drafted by Lee, Chairman of the Northern Central was submitted to the management. It demanded, among other things, a fifty per cent wage rise, the expulsion of certain unpopular contractors and, as in elsewhere, the unconditional release of the thirteen agitators detained at Cheras Road. … Almost immediately after the general cessation was effected, a soviet government, planned by Chiù Tong, was set up in the Collieries. In this government authority was wielded by a high-powered Strike Committee headquartered in the Loh Fah Kong- si. To sustain the determination of the strikers, a Corp for the Detection of Traitors patrolled the mine to ferret out 'labour traitors'. Four coolies were accordingly incarcerated in the Loh Fah Kongsi. Daily, a multi-racial corp of propagandists toured the mine explaining the main objects of 'the struggle' and drove home the message that 'unity is strength'. And a Picket Corp policed the mine to maintain unity and law and order. The Strike Committee further organised possessions, headed by Tamil and Malay labourers, to steel the resolve and lift the morale of the workers. The Collieries, in fact, had become an armed camp with the roads to its main entrance blocked by heavy timbers and ropes. No European dared approach the entrance, and a British officer and a sergeant of the Malay Regiment who did so were turned back by picketeers armed with 'iron bars and poles'. For four days, from March 24th to March 27th, the mine was a communist impérium in imperio , as colonial governmental authority completely vanished. On March 26th the Railway Department had supplies to maintain operation for two weeks, the Selangor electricity power station a week, and the Perak River Hydro-Electric Company only two and a half days. Mines in the Kinta Valley were in imminent danger of working half day. A sympathy strike had been called by five tin mines in Sungei Besi and others were believed likely to follow suit. Understandably, the government feared the outbreak of a general strike by Chinese workers throughout the country. In other words, the communist campaign had reached its peak and the colonial government decided it must meet it head-on or have its position repeatedly challenged thereafter.”

1937-03-24: Operasi polis pertama di Hawthornden Estate: Berikutan bukti yang diperolehi pihak polis pada 21 atau 23 Mac tentang penglibatan anasir komunis di dalam siri mogok ini, pihak kerajaan memulakan operasi polis terhadap peserta mogok ini, di samping memberi tekanan kepada pihak peladang untuk mengemukakan cadangan yang memenuhi sebahagian tuntutan pihak pekerja: “Meanwhile, police officers assiduously gathered informa- tion from their agents and pieced together a convincing scenario of communist intrigues and manipulations. Confronted with this on March 21st or March 23rd, Resident Jones at last approved police intervention.99 The communist challenge to established authority had been proved, and industrial chaos were imminent in the FMS. On March 24th the stage was set for a bloody clash between the strikers and the police. … That day police units conducted the first raid against agitators at the 'armed camp' in Hawthornden Estate. Four were detained and the strikers temporarily dispersed. On March 25th Shenton Thomas arrived in Kuala Lumpur to personally direct the whole operation. … Under pressure, the rest of the planters' representatives then outlined certain tentative concessions for a possible settlement and undertook not to exploit 'the favourable situation' in the wake of a forcible breaking of the strike. This done, Thomas launched a two-pronged offensive aiming at a suppression of the communist organisations behind the unrest and an orderly settlement of the dispute.”

1937-03-25: Serbuan polis ke atas ibu pejabat Jawatankuasa Mogok Kajang di Sungai Ramal: “The same day, March 25th, the police conducted a major raid against the Kajang Strike Committee headquarters at Sungei Ramal, but the leading communist activists escaped.”

1937-03-26: Serbuan polis ke atas peserta mogok di Batu Arang. Setelah pegawai hal ehwal Cina gagal berunding dengan pihak peserta mogok di Batu Arang, pada pukul 3.30 pagi itu, 200 orang anggota polis, dengan disokong oleh 2 kompeni Rejimen Askar Melayu sebagai pasukan simpanan, menyerbu rumah kongsi mereka. Di dalam pergelutan dengan pekerja, seorang terkorban, dan 2 orang tercedera. Selebihnya berjaya disuraikan, dan pimpinan mereka berjaya melarikan diri. Menjelang subuh, 116 orang telah ditangkap: “At this point, the Chinese Protector successfully persuaded the govern- ment to hold a last-minute negotiation for a settlement at Batu Arang. This failed and on March 26th 200 policemen, with two companies of the Malay Regiment on the standby, invaded the Malayan Collieries at 3.30 a.m. on a dark night. As the raiders approached the dimly-lit kongsis, 'an alarm was sounded by the striking of a gong and the blowing of two blasts on a whistle. This was the signal for the pouring out of the kongsi houses of several hundred coolies armed with iron bars, poles, pick- handles, hatchets and files and long-handed axes'. These armed coolies attacked a group of detectives who reacted by firing nine shots, killing an agitator and wounding two others. The other police parties drove the rioters back into the kongsi houses. Prudently, the key strike leaders fled to the blukar in the darkness. At dawn 116 persons were detained and the essential Collieries services immediately resumed. The communist challenge at Batu Arang had collapsed.”

1937-03-27: Mogok di ladang-ladang di Mentakab dan Bentong, Pahang, serta Melaka dan Johor. Tiada kaitan dengan kegiatan aktivis komunis: “Meanwhile, from March 27th the estate strike was carried on its own momentum to the Mentakab and Bentong districts in Pahang, and to Malacca and Johore. There was little communist influence in these strikes.”

1937-03-29: Setelah tumpasnya gerakan mogok di Batu Arang, jawatankuasa mogok Negri Sembilan berdamai dengan majikan, manakala mogok-mogok di bawah jawatankuasa mogok Kajang turut terhenti. Segelintir yang masih tegar berhimpun di ladang Wardieburn dan Hawthornden pada 29 Mac, namun dileraikan oleh pihak polis dengan disokong Rejimen Punjab, dan 40 orang aktivis ditangkap. Pada hari yang sama, polis menyerbu ibu pejabat Parti Komunis Selangor di Jalan Batu Tiga, Klang, dan menangkap 5 orang aktivis komunis. Operasi sebegini berlarutan sehingga Mei 1937, manakala keadaan kembali seperti sediakala lebih awal lagi (2 April): “The effects of the Batu Arang raid were devastating. Cowed, the RWU Strike Committee in Negri Sembilan decided, on its own, to settle with employers. The Kajang Strike Committee became demoralised and the estate strike under its control soon disintegrated. Bold strikers however, regrouped at Wardieburn and Hawthornden Estates on March 29th. They were broken up by a large police party backed by two platoons of the Punjabi Regiment. Forty alleged agitators were detained and the thoroughly frightened tappers resumed work on any terms. The same day, the police raided the Selangor Communist Party headquarters at Batu Tiga Road, Klang. Five communist activists, including Boh Chin, were arrested. In this fashion the rounding up of communist agitators continued into May, although normalcy had returned to Selangor and Negri Sembilan by April 2nd.”

1937-03-31: Persetujuan dicapai. Persetujuan dapat dicapai di antara wakil pekerja dari 21 ladang di Negri Sembilan dengan Persatuan Peladang Negri Sembilan pada 27 Mac 1937, diikuti para perwakilan di Ulu Langat, Selangor 3 hari kemudian (31 Mac 1937), kemudiannya Melaka, Pahang, dan Johor pada bulan April 1937.

Di Negri Sembilan, butiran perkara yang dipersetujui ialah:-

- Gaji dinaikkan ke 75 sen sehari, dan boleh dinaikkan mengikut prestasi penoreh getah

- Getah sekerap: 3 sen per paun

- Penindasan sistem kontrak dipantau

- Gaji dibayar sebelum 10hb setiap bulan secara terus kepada pekerja (tidak melalui kontraktor)

- Notis pemberitahuan kadar gaji 3 hari sebelum tarikh pembayaran

- Kadar bunga tidak lagi dikenakan bagi wang pendahuluan

- Harga barangan di kedai kongsi dikawal oleh pegawai hal ehwal Cina

- Kod Buruh diperluaskan kepada pekerja Tionghua

- Khidmat amah disediakan bagi menjaga anak-anak pekerja, menurut keperluan yang digariskan oleh pegawai kesihatan dan hal-ehwal Cina

- Manfaat ibu bersalin (di hospital ladang atau kerajaan): Anak pertama: 2/6 daripada 6 bulan gaji yang lepas; Anak seterusnya: 2/11 daripada 11 bulan gaji yang lepas

- Pekerja yang sakit dimasukkan ke hospital ladang atau hospital kerajaan kelas ketiga, dengan bekalan makanan dan khidmat perubatan percuma

“On March 28, a 17-point agreement was concluded between the Negri Sembilan Planters' Association and the Chinese rubber estate workers in the state. Three major gains were obtained by the labourers. Firstly, wages were raised; adult workers were assured of an average minimum wage of 75 cents per day; while new or lazy workers would earn 75 cents a day, a good tapper could earn more; extra wages would be paid for gathering scrap at 3 cents per pound. Secondly, the abuses of the contract labour system were checked; wages were to be paid before the 10th of each month, notices showing advances and wages due to each worker were to be posted three days before pay day; no interest would be charged for advances; the maximum prices of goods supplied in the kongsi shops would be fixed by the Protector. These terms meant that wages would be paid direct to the labourers instead of through intermediaries and that the power of the labour contractors were considerably reduced. Thirdly, the provisions of the Labour Code were for the first time extended to the Chinese estate labourers; amahs would be provided for the care of children according to the requirement of the health officers and the Chinese Protectorate; as for maternity benefits, 2/6 of the previous six months wages for the first birth and 2/11 of the previous eleven months' wages for subsequent births would be awarded for workers entering estate or government hospitals; sick workers could be admitted to estate hospitals or third class ward of government hospitals with food and medical treatment provided free of charge.” (Tai Yuen, 1973: |"Labour unrest in Malaya, 1934-1941" (PDF), m.s.152-153).

Di dalam persetujuan di Ulu Langat, sebahagian tuntutan para pekerja telah dipersetujui oleh pihak Persatuan-Persatuan Peladang (dengan sedikit perbezaan mengikut persatuan dan negeri), iaitu:-

- Menaikkan kadar gaji harian kepada 80 sen sehari, kurang 20 sen daripada tuntutan $1 sehari

- Memenuhi sebahagian tuntutan penaiktarafan keadaan tempat kerja, seperti menjaga kebersihan rumah kongsi, juga keseluruhan mutu kebersihan secara amnya, khidmat perubatan percuma, dan bayaran manfaat ibu-ibu bekerja selepas bersalin. Tuntutan-tuntutan yang dipenuhi adalah sebahagian daripada Kod Pekerja yang diamalkan buat kali pertama untuk para pekerja Tionghua, sebagaimana yang telah pun dikuatkuasakan terhadap pekerja India sebelum ini.

- Memberi notis pemberitahuan awal tarikh pembayaran gaji, untuk membanteras penindasan pihak kontraktor terhadap pekerjanya sebelum ini.

“On March 27th the Chinese Protector contacted a labour representative purportedly standing in for workers in twenty-two estates in Negri Sembilan. This led to an agreement between the strikers and the Negri Sembilan Planters' Association on March 28th. Three days later, a meeting at the Merchants' and Miners' Club in Kajang resulted in a similar agreement in Selangor. Early in April the strikes in Malacca, Pahang and Johore were likewise settled without much difficulties. … Although the Batu Arang workers apparently resumed work with a ten per cent wage increase, the estate strikers obtained significant concessions in wages and improvements in working conditions. The Ulu Langat agreement contracted on March 31st reflected salient features of the settlements, especially in Selangor and Negri Sembilan. Under this agreement, the employers conceded to a daily wage rate of eighty cents, twenty cents less than the rate demanded. They also partially met de- mands for improved working conditions such as clean kongsi houses, good sanitary conditions, free medical treatment for sick workers, payment of maternity benefits to working mothers. In other words, certain welfare provisions in the Labour Code, hitherto confined to Indian labour, were to apply to Chinese tappers for the first time. Finally to curb abuses by contractors, the agreement stipulated the posting of notices in the estates in advance of pay days. It should be noted that the settlement terms varied to some extent within and between states because they were individually contracted with different planters or their associations.”