Jadual Kandungan

Penghulu di Zaman Kolonial

Dirujuk oleh

1874: Sistem Residen British

Selepas Perjanjian Pangkor 1874, sistem Residen British telah mengambil alih kuasa eksekutif negeri, termasuk perlantikan dan pengurusan penghulu. Sultan dan para pembesar diraja hanya sekadar penasihat: “In view of the absence of a viable Malay administration and of the chaotic conditions in the states, British rule was unavoidable if the Residents were to carry out successfully the introduction of a sound taxation system, maintain peace and order, and 'open up' the country. Moreover, the economic development of the states, the most important task in the eyes of local officials and commercial interests , could not be realised without an efficient administration. On his own initiative, and backed up by the Governor of the Colony, the Resident proceeded to establish a centralised European administration in the state. While he excluded the Ruler from executive authority, the district administration and the state departments, both controlled and directed by British officers, assumed the functions and powers of the Malay Chiefs. Only at the village level did the Penghulus (the traditional Malay headmen) retain a large measure of authority and influence. However, incorporated into the European administration, the Penghulu system was supervised and controlled by the British. In other words the Rulers and Chiefs became in practice the advisers to the Resident and his British officers, operating largely outside the administrative machine. As the real ruler, the Resident was under fairly tight control and supervision by the Governor of the Straits Settlements.” (Yeo Kim Wah @ Australian National University, 1971: |"British policy towards the Malays in the Federated Malay States, 1920-40", m.s. 6).

Pada mulanya, Sultan dan para pembesar negeri masih diberi peranan penasihat yang agak partisipatif di dalam tatakelola pemerintahan negeri, melalui Majlis Negeri (State Council). Namun menjelang tahun 1890-an, peranan ini kian terhakis: “In the early days of Resident rule the Ruler and the Malay Chiefs enjoyed a vicarious sense of participation in the government since they were frequently consulted by the Resident. A minor attempt was also made to teach the Malay elite the art of modern administration. Malay Chiefs, for instance, sat as magistrates, and the two sons of ex-Sultan Abdullah, Raja Mansur and Raja Chulan, were sent to study at the Malacca High School and eventually joined the Civil Service. Perhaps the most significant instrument through which the Ruler and the Malay elite were brought into intimate association with the new order was the State Council. Though presided over by the Ruler, the State Council was dominated by the Resident who nominated its members and decided its agenda. In the early days of Resident rule, the Council helped to formulate policies, gave both the Malay members and the few Chinese representatives a real sense of participation in government, and provided the constitutional basis for Resident rule. By the 1890's, however, the increasing complexity of administration and the fact that the main lines of British policy had been determined reduced the State Council into a registering body for legislation and decisions taken in the state secretariat.” (Yeo Kim Wah @ Australian National University, 1971: |"British policy towards the Malays in the Federated Malay States, 1920-40", m.s. 8).

1883: Ulu Langat, selepas Raja Kahar

![Tunku Abdul Kahar [Tahir] Tunku Abdul Kahar [Tahir]](/_media/gambar/wangsa-mahkota-selangor-royal-selangor-ku-alam-1.jpg?w=280&tok=50e26f)

Tunku Abdul Kahar [Tahir], Raja yang menjaga Kajang (Wangsa Mahkota Selangor, 19 Jan 2014: |"Y.A.M. Tunku Abdul Kahar [Tahir] ibni Almarhum Sultan Sir ‘Abdu’l Samad Shah") (SEKRETARIAT AKHBAR KERAJAAN NEGERI SELANGOR, 2019: |"SEJARAH NEGERI SELANGOR").

Pada tahun 1883, pihak British diwakili Syers telah mengambil alih pengurusan daerah Ulu Langat daripada Raja Kahar. Antara para penghulunya ketika ini ialah Raja Mahmud (Ulu Semenyih), Raja Daud (Ulu Langat), dan Syed Yahya (Cheras): “In 1883 the semi-traditional regime of Raja Kahar as Malay Magistrate was replaced by the formal creation of the Ulu Langat administrative district, though shortage of staff made it necessary that Syers, the superintendent of police, should act temporarily as the first district officer. The district was divided into five mukim (subdistrict), each in the charge of a Malay penghulu (headman), three of whom deserve mention. Raja Mahmud of Ulu Semenyih was the youngest son of Sultan Mohamed, who in his last years appointed Mahmud, a boy of about 10, to the post of Raja Muda. But in the power struggle that followed his father's death in 1857, Mahmud lost the succession (and the office of Raja Muda) and retired to the periphery of his lost kingdom. In the absence of an established local Malay dominant family, Mahmud, who was intelligent and capable, became the recognized leader of the Ulu Langat Malay community. Raja Daud of Ulu Langat mukim had, as a young man, been the paramour of the wife of Sultan Abdullah of Perak (r. 1874-6). He was 'a man of pleasing features, extremely quiet, and of courtly manners [which] … concealed a firm determination and a dauntless courage'. In his later years at Ulu Langat, Daud was 'a charming old man to meet' and no one would have suspected his scandalous past. Syed Yahya, penghulu of Cheras, was the son of an Achehnese immigrant, Syed Idris, who had settled at Rekoh. After his death, he became a saint whose tomb was a local keramat (shrine). Yahya had married the daughter of his predecessor, Che Ngah, and, like his father, he was 'a great advocate of pepper planting' with 3 acres under 7,000 pepper vines. But his efforts to persuade his people to follow his example were ineffective as 'the want of money is the stumbling block'. It was one sign, among many, of the gap between the general body of Sumatran settlers and the upper-class penghulu.” (J.M. Gullick, 2007: |"A Short History of Ulu Langat to 1900"), m.s. 11-12).

LATAR PERISTIWA: Penghulu Syed Yahya, Cheras.

1887-01-01: Rekoh: Penghulu Che Man

Perlantikan “Che Man” sebagai Penghulu Kajang & Reko, oleh Residen Selangor, melalui cap kuasa Sultan Selangor. Beliau menggantikan Raja Kahar, putera Sultan Abdul Samad, yang dikatakan tidak mempunyai rumah di kawasan ini, dan tidak pernah membuat lawatan sejak setahun setengah yang lalu. Che Man disebut sebagai seorang “anak negeri” yang disukai “orang dagang” dan masyarakat umumnya. Beliau juga dikatakan rakan rapat Raja Kahar. Latar perlantikan:-

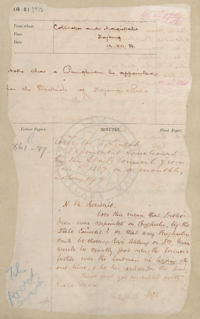

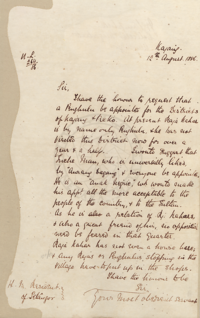

- 12/08/1886: Perlantikan beliau telah dicadangkan oleh J.A.G. Campbell (Majistret daerah Ulu Langat), atas dasar beliau sebagai anak negeri serta sahabat baik Raja Kahar: “I have the honour to request that a Penghulu be appointed for the Districts of Kajang & Reko. At present Raja Kahar is by name only Penghulu, & he has not visited this District now for over a year & a half. I would suggest that Inche Man, who is universally liked, by “Aurang Dagang” & everyone be appointed. He is an “Anak Negrie”, who? would make his appt all the more acceptable to the people of the country, & to the Sultan. As he is a relation of Rj. Kahars, & also a great friend of his, no opposition need be feared in that quarter. Raja Kahar has not even a house here; & any Rajas or Penghulus stopping in the village have to put up in the shops. - J.A.G. Campbell, Collector & Magistrate, Ulu Langat.” (PEJABAT SETIAUSAHA KERAJAAN NEGERI SELANGOR, 12/08/1886: |"ASKS THAT A PENGHULU BE APPOINTED FOR THE DISTRICT OF KAJANG & REKO").

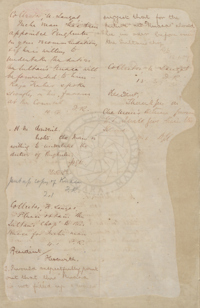

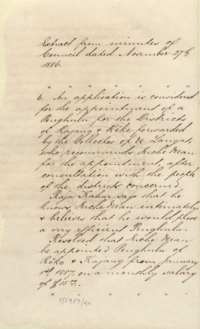

- 27/11/1886: Cadangan perlantikan telah dipersetujui oleh ahli Council negeri Selangor: “Extract from minutes of Council dated November 27th 1886: 6. An application is considered for the appointment of a Penghulu for the District of Kajang & Reko, forwarded by the Collector of U. Langat, who recommends Inche Man for the appointment, after consultation with the people of the districts concerned. Raja Kahar says that he knows Inche Man intimately & believes that he would prove a very efficient Penghulu. Resolved that Inche Man be appointed Penghulu of Reko & Kajang from January 1st 1887, on a monthly salary of $15.00.” (PEJABAT SETIAUSAHA KERAJAAN NEGERI SELANGOR, 24/09/1890: |"ASKS FOR THE APPOINTMENT OF PENGHULU OF KAJANG VICE CHE MAN").

Che Man seterusnya menjadi penghulu Kajang & Rekoh selama sekurang-kurangnya 6 tahun, berdasarkan beberapa rekod urusan beliau sehingga tahun 1892:-

- “STATES THAT INCHE MAN PENGHULU OF KAJANG HAS APPLIED FOR A LOAN OF $200 FOR THE PURCHASE OF CARTS” (PEJABAT SETIAUSAHA KERAJAAN NEGERI SELANGOR, 26/02/1889: |"STATES THAT INCHE MAN PENGHULU OF KAJANG HAS APPLIED FOR A LOAN OF $200 FOR THE PURCHASE OF CARTS").

- “RECORD ON THE APPLICATION FROM PENGHULU CHE MAN FOR A LOAN OF $40 WHICH HE PROPOSED TO REPAY BY MONTHLY INSTALMENTS OF $10.” (PEJABAT SETIAUSAHA KERAJAAN NEGERI SELANGOR, 09/06/1892: |"PENGHULU CHE MAN - APPLIES FOR A LOAN OF $40.00/100").

LATAR PERISTIWA: Perihal J.A.G. Campbell.

1896: Negeri-Negeri Melayu Bersekutu

Pada tahun 1896, Selangor, Perak, Negeri Sembilan, dan Pahang, disatukan di bawah Negeri-Negeri Melayu Bersekutu, dengan Frank Swettenham sebagai Residen Jeneral yang pertama. Pentadbiran pusat semakin mendominasi, antaranya memacu pembukaan besar-besaran ladang dan lombong, serta pengurusan tenaga buruh asing bagi mengerjakannya. Hal ini telah mengurangkan lagi peranan sultan dan pembesar negeri dalam hal ehwal pentadbirannya, terhad kepada hal-hal berkaitan agama dan adat budaya. Malah perlantikan serta pengurusan penghulu juga turut diberikan kepada pihak British, melalui surat kuasa Sultan. Ketika itu, penghulu bertindak sebagai orang tengah di antara pegawai daerah British dengan penduduk tempatan: “After the FMS came into being in 1896, a federal administration was established which was likewise British-controlled and directed. The rapidity with which this was erected showed that British officials were more interested in economic development than in ruling the country through traditional leaders and institutions. … In short the Federal Council centralised both financial and legislative powers in Kuala Lumpur by working closely with the Federal Treasury and the Legal Adviser's Department under the general oversight of the Chief Secretary. The State Councils were left with local matters concerning Malay religion and custom, mosques, political pensions, penghulus, death sentences, and conversion of agricultural and mining lands. … In the sphere of practical administration, the Ruler still presided over the State Council and exercised a vital say in its recruitment of Penghulus and Kathis (religious magistrates). His seal was required to validate certain state documents like the Kuasas of Penghulus and Kathis, but such documents were prepared in the State Secretariat and needed to be first sanctioned by the Resident. The Ruler's signature gave legal force to laws enacted by the state and federal legislatures. … As in pre-Federation days, the District Officer maintained peace and order in the district, performed judicial duties of a First-class magistrate, took charge of land administration and revenue-collecting, and supervised the Penghulu administration. … In pre-British days the Penghulu, as the village head, was a part of the political structure of Perak, Selangor and Pahang. Mainly for reason of economy and shortage of manpower, the Penghulu system was incorporated into the district administration. The Penghulu now became the link between the Malay ra'ayat and the District Officer who replaced the local chief. His jurisdiction was also enlarged to a few villages which formed a mukim (parish) into which the district was divided. The Penghulu continued to exercise strong influence in the village, provided the government with an invaluable fund of local knowledge, and was a highly useful instrument for local government.” (Yeo Kim Wah @ Australian National University, 1971: |"British policy towards the Malays in the Federated Malay States, 1920-40", m.s. 47, 55, 74, 75).

Cara perlantikan Penghulu: dilantik oleh Sultan dalam majlis negeri, setelah diusulkan oleh jawatankuasa Penghulu dan diluluskan oleh Residen. Kriteria utama pemilihan ialah orang tempatan (kecuali jika ada terdapat konflik), populariti, perwatakan, dan tahap pendidikan. Keutamaan kriteria ini berbeza-beza mengikut negeri: “The Penghulus in each state were appointed by the Ruler-in-Council after they were recommended by a Penghulu Committee and approved by the Resident. The policy of Penghulu recruitment, however, varied from state to state according to local conditions. In general the recruitment was determined by three common criteria: local origin and popularity, force of character, and educational attainment. But the weight attached to each of these factors in the selection of Penghulus varied from state to state. In In Pahang, owing to the relatively undeveloped character of the state, the territorial factor was paramount and Penghulus were appointed from the most suitable men in the mukims. Only when there were no suitable local candidates or when the mukims were split into rival factions were outsiders appointed. In Perak and Selangor more attention was paid to the other two factors. Owing to the presence of large communities of immigrant Malays, a strong man was considered essential in many mukims in Selangor. Negri Sembilan also tended to appoint Penghulus who had a strong personality and had performed outdoor duties in the district. Apart from these qualities, Penghulus were occasionally appointed on account of purely local considerations. For instance, in the Tampin and Kuala Pilah Districts Penghulus must be Rembau Malays because their duties invariably affected the Adat. Until the 1930's the intervention of the Ruler or the Undang was at times decisive in the appointment of a particular Penghulu, even against the vehement protest of the District Officer concerned.” (Yeo Kim Wah @ Australian National University, 1971: |"British policy towards the Malays in the Federated Malay States, 1920-40", m.s. 87-88).

1904-10-17: Cheras: Penghulu Raja Hussein

“Raja Hussein, the new Penghulu of Cheras reported himself on the 17th. An English Speaking Penghulu is a novelty in this part of the country. … - O.F.Stonor. District Officer, Ulu Langat.” (Arkib Negara 1957/0119358W, 14/11/1904: |"MONTHLY REPORT FOR OCTOBER, 1904").

1920-1940: Penghulu sebagai Pegawai Kerajaan

Menjelang tahun 1930-an, jawatan penghulu beransur menjadi seakan sebahagian daripada pegawai kerajaan British. Pemilihan lantikannya adalah berdasarkan kecekapan dan tahap pendidikan, bukan lagi keturunan. “After Federation the Penghulu administration gradually developed into a mukim bureaucracy. The Penghulu schemes of the various states came to embody terms of service somewhat similar to those of ordinary government servants. Hereditary successions, still important in pre-Federation days, were now rare. By the 1930's the practice was to appoint Assistant Penghulus who would eventually be promoted to Penghulus on grounds of efficiency. The recruitment of Penghulus came to resemble that of ordinary government officers at least in Selangor and Perak. In 1935 Selangor introduced a Penghulu Scheme in which the selection of Penghulus was mainly determined by educational qualification and general knowledge. Suitable candidates were selected as Assistant Penghulus after an oral and written examination on Malay composition, general knowledge and History of Selangor. To be promoted to a Penghuluship, these assistants were required to pass an oral examination on certain sections of the Land Code and Land Regulations, the Criminal and Civil Code, and the General Orders. … The Penghulu was the leader of social life in the mukim. His office and functions raised him above the ra'ayat. and this was enhanced by a kuasa from the Ruler. …” (Yeo Kim Wah @ Australian National University, 1971: |"British policy towards the Malays in the Federated Malay States, 1920-40", m.s. 88).

Dengan berkembangnya kegiatan ekonomi serta kepelbagaian masyarakatnya, bidang tugasan dan pengurusan penghulu kian membesar. Beliau dibantu oleh Kadi (bidang pengurusan dan pengadilan berkaitan keagamaan) dan Ketua Kampung (wakil setiap kampung, biasanya mengikut suku penduduk kampung tersebut): “As the agent of the government in the village, the Penghulu performed numerous functions such as maintaining order and settling disputes. However during the interwar years he no longer collected revenue in the mukim, a major function of his 19th century predecessor. After 1933 he also stopped sitting in judgement over Europeans guilty of petty offences. Though the official reason was that Penghulus were reluctant to convict Europeans, this ruling was probably also influenced by the desire to maintain white prestige. In other directions the duties of the Penghulu increased enormously during the interwar period. For instance, he had to help enforce rubber restriction, assist land settlement and alienation, and supervise village night-markets. In undertaking these multifarious duties, the Penghulu was assisted by the kathis and (in Selangor and Perak) the ketuas kampong (village Elders). The kathi, a post which in the opinion of one District Officer ’perfectly suited the Malay temperament', settled religious disputes, solemnised muslim marriages, administered the law relating to divorce and inheritance of property, and tried minor cases of matrimonial offences and breaches of religious observances. The Ketuas Kampong were officially appointed during the first decade of this century to help the Penghulus tackle the vast increase of work in the mukim ard control the large immigrant Malay communities in Perak and Selangor. The Ketua Kampong advised the Penghulu on village development, served notices, and discharged other minor duties. Generally Penghulus found Ketuas Kampong of local Malay origin easy to cope with and at times, not closely supervised by District Officers, left all the work to them. But Ketuas Kampong of immigrant stock, who formed the majority in Selangor, were extremely difficult to handle when they were hostile to the Penghulu. Such frictions fortunately were not frequent, and by the 1930's the Ketuas Kampong had come to provide the 'local touch' to the mukim administration in Selangor and Perak. To a significant extent, what the new breed of Penghulus lacked in village ties was corrected by the Ketuas Kampong.” (Yeo Kim Wah @ Australian National University, 1971: |"British policy towards the Malays in the Federated Malay States, 1920-40", m.s. 90-91).

Pengakuan penting: Kami bukan ahli sejarah! Sila klik di sini untuk penjelasan lanjut.