Jadual Kandungan

Candu di Malaya

Dirujuk oleh

Perihal

Candu telah pun wujud di kalangan bangsawan Melayu, sebelum gejala tersebut dibawa masuk ke Tanah Melayu oleh para pengusaha dan pekerja lombong dari Cina mulai abad ke-18: “…pada awalnya majoriti penghisap candu adalah golongan bangsawan Melayu yang melihatnya sebagai satu bentuk kemewahan. Namun dengan kemasukan buruh Cina secara besar-besaran terutamanya ke kawasan perlombongan bijih timah sekitar akhir abad ke-17 dan awal abad ke-18, keadaan ini berubah sama sekali. Dalam tempoh ini boleh dikatakan berlakunya satu transisi dimana golongan buruh Cina muncul sebagai majoriti penghisap candu. Dianggarkan pada tahun 1898 sahaja, terdapat sebanyak 61,750 penghisap candu Cina berbanding 1,300 penghisap candu berbangsa Melayu.” (Jayakumary Marimuthu, Azmi Arifin @ E-PROCEEDINGS International Conference on Sustainability, Humanities and Civilization (ICSHAC), November 2018: |"PEMBANTERASAN TABIAT MENCANDU DAN PERANAN GERAKAN ANTI-CANDU DI NNMB SEBELUM TAHUN 1910", m.s.35).

Budaya candu berkait rapat dengan sistem serta budaya pengurusan pekerja lombong di Tanah Melayu, yang terawal direkodkan pada tahun 1867. Tempat tinggal, bekalan makanan, serta kemudahan hidup para pekerja diuruskan sepenuhnya oleh pemilik atau pengusaha lombong. Mereka terpaksa tinggal di rumah kongsi di dalam kawasan lombong. Selain berada jauh dari kaum keluarga, keadaan ini menyebabkan mereka turut putus hubungan dengan masyarakat setempat. Candu menjadi antara pilihan aktiviti di waktu rehat, setelah seharian bekerja di lombong: “Malaya, as it was then known, was being carved-out of the rugged terrain and jungles in the early 19th century. In opening up the country and developing its tin mines, rubber and pepper estates, the British brought in huge numbers of Chinese and Indian workers into Malaya to work in the tin mines, rubber plantations and pepper estates respectively. The Chinese were the first people who introduced into the country the habit of opium smoking. Employment in the new country brought them enough money to spare. There was some period of leisure after a gruelling day’s work, but there were no amenities with which they could occupy themselves. Most of them had left their families behind in their homeland. Opium smoking thus became one of the outlets. Some smoked it as a medicine, to cure aches and pains and ward off diseases (opium was believed to have a beneficial effect on tuberculosis of the lungs, diarrhoea, and malaria). At that time, it was not considered harmful and there was no restriction or taboos as to its usage. It has been recorded that opium consumption among some of the Chinese in Singapore and the Straits Settlements was evident since 1867.” (Abdul Rani Kamarudin @ Jurnal AADK, Jilid 1, 2007: |"The Misuse Of Drugs In Malaysia : Past And Present", m.s.4).

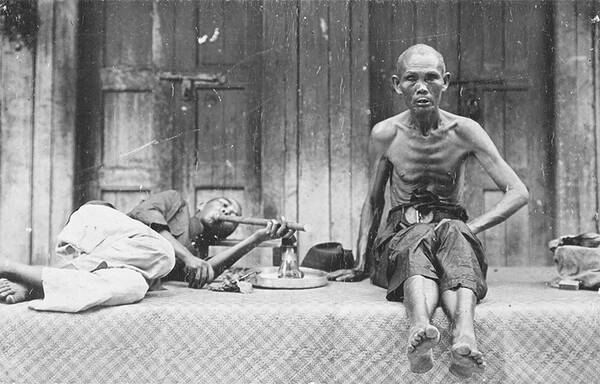

Pekerja Cina sedang menghisap candu, akhir kurun ke-19 / awal kurun ke-20: “Emaciated Chinese labourers smoking opium, late 19th century–early 20th century. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board” (Diana S. Kim, 1 Oct 2020: |"The Sticky Problem of Opium Revenue").

Peranan British

Selain industri candu itu sendiri, gejala tersebut turut menguntungkan pihak British, terutamanya ketika zaman pentadbiran Negeri-negeri Melayu Bersekutu (NNMB), melalui kutipan cukai dan sewa secara sistematik dan berpusat: “Kemasukan berterusan buruh Cina menjadi suatu rahmat buat kerajaan NNMB apabila tabiat mencandu mereka digunakan sebagai instrumen yang dikenakan cukai. Dalam mengaut keuntungan melalui candu, kerajaan British memperkenalkan Sistem Pajakan Hasil Candu. Di bawah sistem ini, pihak kerajaan memperolehi hasil melalui pengenaan duti import ke atas candu mentah dan juga sewa pajakan ladang candu. Antara tahun 1898 hingga 1907, hasil candu menyumbang dari 9.1 peratus hingga 18.6 peratus daripada keseluruhan hasil pendapatan kerajaan NNMB.” (Jayakumary Marimuthu, Azmi Arifin @ E-PROCEEDINGS International Conference on Sustainability, Humanities and Civilization (ICSHAC), November 2018: |"PEMBANTERASAN TABIAT MENCANDU DAN PERANAN GERAKAN ANTI-CANDU DI NNMB SEBELUM TAHUN 1910", m.s.35-36).

Hal ini menerima tentangan daripada sebahagian warga British sendiri, sejak seawal tahun 1843 lagi. Namun ianya hanya mendapat sokongan banyak pihak di Tanah Melayu, termasuk daripada kalangan pentadbir British serta usahawan Cina, mulai tahun 1906: “Buat kali pertama, isu candu di bawa ke Parlimen Britain pada 4 April 1843, apabila Lord Ashley membangkitkan bantahan terhadap perdagangan candu. … Walaupun usul tersebut tidak mendapat sebarang respons positif dari pihak kerajaan tetapi ia telah membuka jalan kepada penyokong anti-candu untuk mempersoalkan perdagangan candu secara terang-terangan. Dengan penubuhan sebuah pertubuhan anti-candu, Society for the Suppression of the Opium Trade (SSOT) pada tahun 1874, golongan penyokong anti-candu mengharapkan pertubuhan ini mampu mengubah pendirian kerajaan. … Pada 30 Mei 1906, seorang ahli Parlimen Britain Theodore Taylor mengemukakan usul bantahan terhadap perdagangan candu dan mendesak kerajaan Britain untuk menamatkan dengan kadar segera … Melalui pengemukaan usul bantahan tersebut, barulah kerajaan Britain mengubah polisi candunya setelah sekian lama. Keputusan positif kerajaan Britain terhadap usul Theodore Taylor menjadi suntikan semangat bagi penyokong anti-candu Britain untuk bergerak ke Tanah Melayu dalam usaha memperkukuhkan gerakan anti-candu tempatan.” (Jayakumary Marimuthu, Azmi Arifin @ E-PROCEEDINGS International Conference on Sustainability, Humanities and Civilization (ICSHAC), November 2018: |"PEMBANTERASAN TABIAT MENCANDU DAN PERANAN GERAKAN ANTI-CANDU DI NNMB SEBELUM TAHUN 1910", m.s.37-38).

Mulai 1910, pihak British mula mengawal selia kegiatan import, penjualan, dan pengedaran candu di Tanah Melayu, serta mengenakan cukai ke atasnya. Namun dengan cara ini mereka masih terus-menerus mendapat keuntungan di setiap peringkat: “… In 1910, the British Government took over the importation, sale and distribution of opium. The Government licensed all retail shops, while mine owners and other large employers of Chinese labour imported their own opium, converted it into chandu, and dispensed it to their own employees. After a good many years the Government, in some states, collected their own taxes on opium, and while that policy did not make the slightest difference to the consumers, it enabled the Government to calculate this source of revenue for each successive period of three years.” (Abdul Rani Kamarudin @ Jurnal AADK, Jilid 1, 2007: |"The Misuse Of Drugs In Malaysia : Past And Present", m.s.4).

Berikutan Konvensyen Geneva 1925, ia mula dihentikan secara beransur-ansur, sehingga dilarang sepenuhnya dalam Akta Dadah Merbahaya 1952: “The Geneva Convention on Drugs held on the 19th day of February 1925, prompted the British to impose restrictions on the sale and consumption of opium. Registered opium smokers or authorised consumers however continued to ‘enjoy’ this privilege. By 1929, the Federated Malay States had 52,313 registered opium users. A further restriction was imposed in 1934, as a result of a treaty signed in Bangkok on the use of opium. Only those who had a doctor’s recommendation were allowed to use it. By 1941, there were 75,000 opium users and it was estimated that the number of those who were not registered might well be double. After World War Two, the British prohibited the unauthorised use of opium. … In order to prohibit the possession, use, manufacture, sale, and importation of dangerous drugs, the Dangerous Drugs Ordinance of 1952 was promulgated by the High Commissioner with the consent of the Rulers in Council of the Federation of Malaya.” (Abdul Rani Kamarudin @ Jurnal AADK, Jilid 1, 2007: |"The Misuse Of Drugs In Malaysia : Past And Present", m.s.5-6).

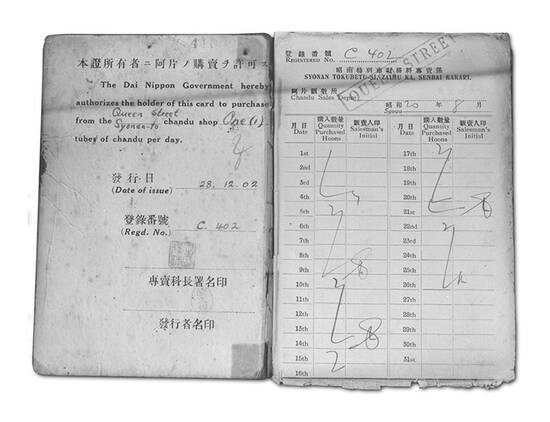

Kiri: Lesen membeli candu (zaman pendudukan Jepun): “An authorisation card to purchase chandu (opium) from Queen Street in 1942, during the Japanese Occupation. Chew Chang Lang Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.” (Diana S. Kim, 1 Oct 2020: |"The Sticky Problem of Opium Revenue").

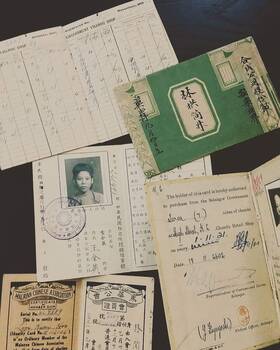

Kanan: Lesen membeli candu (zaman pendudukan Jepun): “My great grandparents' opium licenses for the Government Chandu Shop (originally granted by the British, but these ones dating from the Japanese Government of Selangor during the Occupation), along with other family documents (including my Ah Kong's MCA membership lol).” (Soon-Tzu Speechley 孫子 @ Twitter, 18 Feb 2020: |"My great grandparents' opium licenses for the Government Chandu Shop").

Pengakuan penting: Kami bukan ahli sejarah! Sila klik di sini untuk penjelasan lanjut.