Jadual Kandungan

Rudinara / Salinger House (1992-2019)

Dirujuk oleh

Perihal

“Rudinara Rumah Jati Melayu

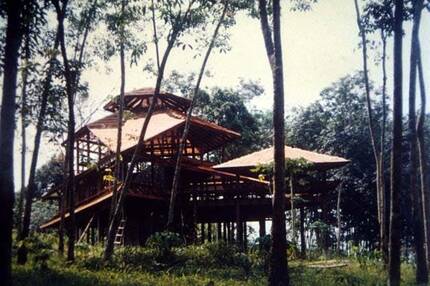

Di Kampung Sungai Merab Luar, terdapat sebuah rumah tradisional Melayu yang menjadi kebanggaan kampung ini. la terletak di suatu kawasan ladang getah seluas 2 ekar. Rumah ini merupakan sebuah rumah kayu dua tingkat yang penuh dengan ciri-ciri seni bina Melayu. Rumah tersebut dimiliki oleh Profesor Rudin Salingar seorang ahli akademik berbangsa Perancis yang telah memeluk agama Islam. Antara keistimewaan rumah tersebut ialah pakunya diperbuat daripada kayu Cengal. Keunikan dan keistimewaannya melayakkan ia menerima anugerah Aga Khan Award

for Architecture pada tahun 1998. Rudinara adalah satu-satunya rumah kediaman di dunia yang menerima anugerah tersebut. la merupakan satu-satunya produk pelancongan di Kampung Sungai Merab dan perlu diketengahkan oleh agensi dan badan pelancongan di Malaysia dan Selangor.”

(Sumber: Discovery Research Consultant Management Sdn. Bhd. b/p Unit Perancang Ekonomi Negeri (UPEN) Selangor, 2007: “Koleksi Cerita Asal Usul dan Sejarah Daerah Sepang”, m.s. 46).

“The Salinger house, or Rudinara, is a single-family residence built exclusively of timber in the traditional way of the Malays. … The Salinger house is located in an old rubber plantation in the district of Bangi, 15km south of Kuala Lumpur, off the main north-south highway. Bangi was originally an outlying area with a small rural settlement, called the Kampung Sungai Merab Luar. A university was set up, followed by a small industrial estate that lead to the slow residential development of the area. The immediate surroundings of the site consist of two to three storey, nondescript, concrete villas owned and occupied by teachers from the neighbouring religious schools and university.” (Hana Alamuddin, May 1998: |"1998 Technical Review Summary: Salinger Residence", m.s.5).

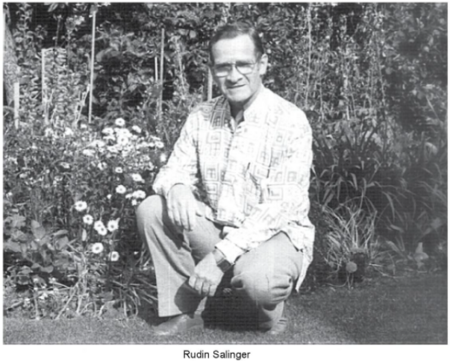

Pemilik Asal

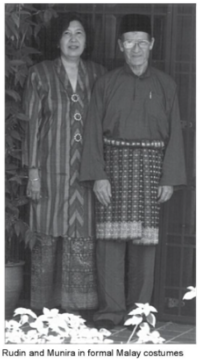

“The client, Dr. Haji Rudin Salinger, is an American citizen who has lived in Malaysia for over thirty years and has a keen interest in Malay culture. Dr. Salinger and Puan Munira Salinger, his wife, wanted to build their home in the rural area near the university where he worked. They specifically wanted a modern house that reflected Malay culture and their Islamic faith. … The client, Dr. Haji Rudin Salinger, is of French and German origin. Born in Canada and educated in the United States, he came to Malaysia in his thirties as a Peace Corps volunteer. He returned a few years later, converted to Islam, settled and married. He is a physicist and has lived and worked in Malaysia for over thirty years. He is involved in education and has worked with UNESCO and taught at the National University for fourteen years. He has written six books on education, has three patents of his name, and has written over fifty articles about on subjects including Malay crafts, cooking, and culture.” (Hana Alamuddin, May 1998: |"1998 Technical Review Summary: Salinger Residence", m.s.5, 8-9).

“Rudin, as we came to know him, told us that he was born in Canada, quite by happenstance. His French parents, happened to be in Canada where his father’s engineering job took them at the time. Rudin’s own career as a professor, took him to Malaysia during the 1950’s. There he met his future wife, Munira, a Malaysian lady. Upon marriage Rudin became a Muslim and wholeheartedly began to learn about the Malaysian culture. Now he is a well-respected authority on the culture of his adopted country.” (M. Maxine George @ Magic Carpet Journals: |"Rudinara, A Malaysian Cultural Experience").

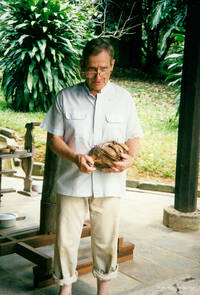

““My mother originally left France to work in a newspaper in French Indo-China. She and her sister were sent to Hawaii for a conference and then decided to visit San Francisco.” Dato’ Salinger points at the date on the newspaper; 14 July 1933. Bastille Day. “This photo shows my mother the day after she landed in San Francisco,” he explains, “She ended up as editor of the paper. My aunt was an actress in the Bay area”. He himself was the youngest of four boys born into a lineage rich in both mechanical and intellectual achievement. “I got all the mechanical talent. I can fix anything with my hands,” says Dato’ Salinger, peering through his glasses down at his gnarled fingers. His job as a physics professor led him to Malaysia beginning a lifelong dedication to teaching and learning about – as well as preserving and developing – Malaysian crafts and achievements.” (ExpatGo Staff, June 13 2012: |"Handmade History").

Kiri: Rudin Salinger

Kanan: Rudin dan Munira Salinger

(Sumber: Munira M. Salinger, 2016: "My Story", m.s.175,178).

“UKM55: Dr. Rudin Salinger: Dari sukarelawan Peace Corps, menjadi Pengarah Pusat Teknologi Pendidikan UKM (PTP). Dato' Dr.Haji Rudin Salinger menyertai program sukarelawan 'Peace Corps' pada tahun 1960 dan telah berkhidmat di beberapa buah negara,sehingga pada tahun 1966, beliau berkhidmat di Malaysia. Pada tahun 1980, beliau mendapat tawaran menyertai UKM sebagai ahli akademik, khusus untuk mengajar bidang sains, fizik dan matematik. Beliau kemudiannya dilantik sebagai Pengarah Pusat Teknologi Pendidikan UKM (PTP). Dr. Rudin juga merupakan tokoh dalam bidang senibina, kediaman beliau di Sungai Merab Luar, Kajang yang dinamakan 'Rudinara' pernah menerima anugerah berprestij dalam senibina, iaitu Anugerah Aga Khan pada tahun 1998. PTP UKM sendiri telah mengalami evolusi dalam tadbir urusnya, kini PTP UKM dikenali sebagai Penerbit UKM.”

(Sumber: Harith Faruqi Sidek, 21 Mei 2025: "UKM55: Dr. Rudin Salinger").

“The initial brief of the Salinger house was a weekend retreat away from the hustle and bustle of the city. Dr. Hj. Rudin Salinger and his wife Puan Munira Salinger were then living in Petaling Jaya, 15 minutes drive from the central Kuala Lumpur. At the time, the site was highly undeveloped and essentially a rural district located on the outskirts of a small Malay village. With their knowledge and understanding of Malaysian culture, the clients were looking to build a modern home which would embrace their Malaysian heritage and Muslim faith. Having lived in Malaysia for over 30 years, Dr. Hj. Salinger had developed a great interest in Malaysian's heritage and culture. This has since a number of papers written on timber woodcarving and handmade roof tiles as well as the ability to cook many local dishes.” (Malaysia Architecture, 11 February 2012: |"Salinger House by CSL Associates").

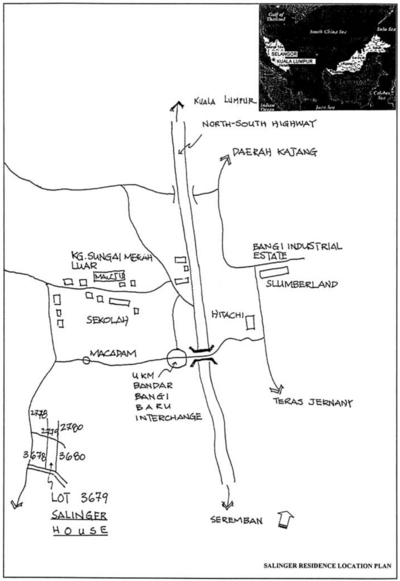

Lokasi Asal

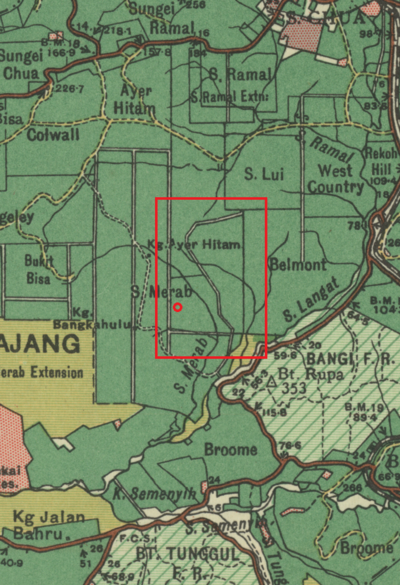

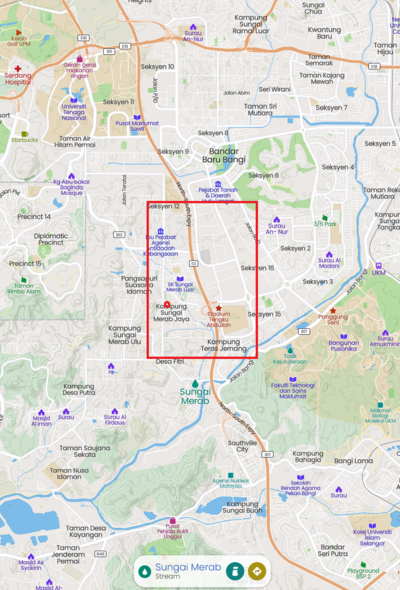

Peta lokasi di Bangi: “The three-acre site (12'140 m2) is rectangular with gentle slopes from West to East of approximately 10%. The land is heavily wooded with rubber trees and is approached from the South. … It is located virtually in the middle of the north-south length of the site and about 6 m away from the Western boundary.” (Hana Alamuddin, May 1998: |"1998 Technical Review Summary: Salinger Residence", m.s.5).

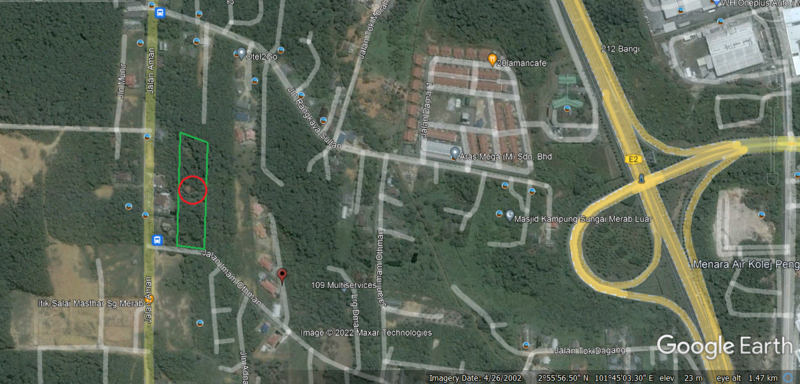

Kiri: Lot 3679, 1992 (Hana Alamuddin, May 1998: |"1998 Technical Review Summary: Salinger Residence", m.s.11).

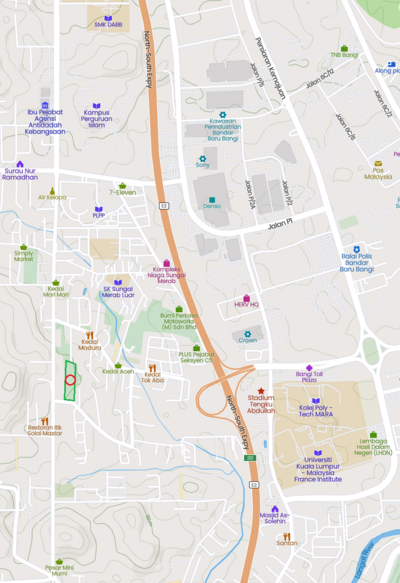

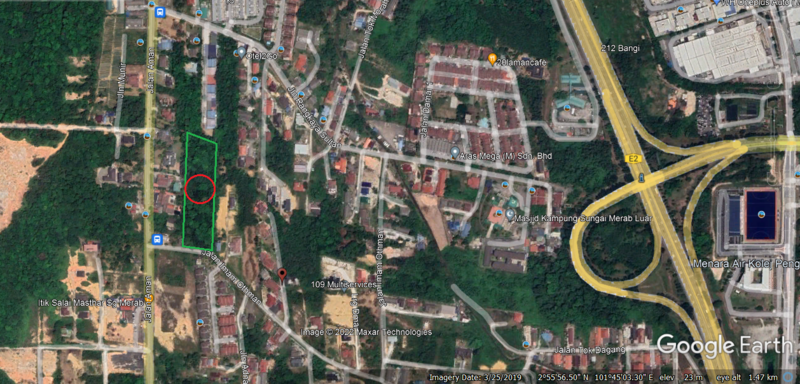

Kanan: Lot 3679, kini, ditandakan dengan petak hijau. Anggaran lokasi binaan rumah ditandakan dengan bulatan merah (Mapcarta).

Peta lokasi di Bangi, dari jarak jauh. Peta lokasi jarak dekat di atas, ditandakan dengan petak merah. Anggaran lokasi binaan rumah ditandakan dengan bulatan merah.

Kiri: Anggaran peta lokasi, tahun 1950, iaitu sebahagian daripada Ladang Sungai Merab (berdasarkan peta Surveyor General, Malaya, 1950 @ Australian National University: |"Malaysia, Malaya, Selangor 1950, Land Use, South Sheet, 1950, 1:126 720").

Kanan: Anggaran peta lokasi, kini (berdasarkan Mapcarta).

Peta lokasi Salinger House (Lot 3679, ditandakan dengan petak merah), kini. Anggaran lokasi binaan rumah di dalam bulatan merah (Majlis Perbandaran Sepang, 2022: Sistem Pengurusan Kebenaran Merancang (EKM)).

Gambar satelit bagi peta lokasi GIS di atas (ditandakan dengan petak merah), tangkapan tahun 2002. Kemungkinan binaan rumah masih kelihatan di dalam bulatan merah. (Google Earth).

Gambar satelit bagi peta lokasi GIS di atas (ditandakan dengan petak merah), tangkapan tahun 2019. Rumah telah dipindahkan, dan tidak lagi kelihatan di dalam bulatan merah. (Google Earth).

1986-1992: Pembinaan

Ketika dalam pembinaan, Februari 1986 hingga Jun 1992: “The house was built completely by hand by the traditional Malay carpenters from the state of Kelantan on the east coast of the country. The only machinery used was a small concrete mixer. Three to four carpenters would work at one time on the project which took six an a half years to build. The staircase and stone core were the first things to be built. Then, the structural columns independent of the stairs were put up. The columns were lifted into place by a series of pulleys, hoists, and ramps. The columns were cut with an axe and are planed into eight-sided posts. At the lifting of the first column, Surat Yassine (Tiang Sri), from the heart of the Qur'an, and the Doa'a Salamat were read by the religious teacher. The two readings form a local, traditional building ritual performed to ensure the success of the endeavour. As the stone structure was built up, the timber structure was tied into it. The roof was then assembled on the ground, taken apart, lifted by a series of pulleys, and reassembled 16m above the ground in mid-air. The tiles were then taken up by a series of ramps and installed so as to quickly gain cover from the rain. The floors followed and finally the timber walls and internal finishes. … The timber for the house came from three chengal trees selected by the master carpenter Ibrahim Adam and a Forestry Officer. Two were selected from the forests of the Gua Musang area of Kelantan and the third from Hulu Besut in Terengganu. These were felled, cut, and brought to the site by lorry. Because the maximum size of the timber allowed on the lorry is 24 ft, the timbers had to be cut and then joined again on-site. The builders were a team of six Malay carpenters, originally from the Bachok district. Although the technology of timber building used was very traditional, the geometry of the house and the stone core was new. The only consultant involved was the architect, who has extensive experience building with timber in Malaysia and is a believer in the use of timber as a low energy, sustainable material best suited to the climate and environment of this country. No engineer was involved. The design was started in June 1985 and was finalised in October 1985. Work started on site in February 1986 and ended in June 1992.”

(Sumber: Hana Alamuddin @ Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), May 1998: |"1998 Technical Review Summary: Salinger Residence", m.s.7).

“The basic design for Rudinara was drawn from Architect Jimmy Lim’s sketch of a triangular-shaped house, which was later modified to include an extended veranda. However, much of the original plan remained on paper, as the master craftsman, Ibrahim Adam, from the Peninsular Malaysia’s State of Kelantan that Datuk Rudin had identified, made considerable modifications to the actual design of the house as it was constructed. It must have been the challenge of building a non-rectangular house using traditional methods that captured Ibrahim’s interest. Together with four septuagenarian assistants, Ibrahim began masterminding and leading the six-and-a half-year project to build Rudinara, and unique, one-of-a-kind abode for a nature-loving couple. What was remarkable is the fact that Ibrahim was blind in one eye and had no right hand.” (Ismailimail, November 9, 2006: |"Rudinara – A Handmade House – Aga Khan Award for Architechture").

““The core of the house is a stone cylinder with walls over a meter thick,” says Dato’, slapping the wall to emphasize its solid construction. The house hangs from the core; two levels capped with a handmade crescent and star. The wood pillars holding up the structure are six-sided, allowing them to be joined in interesting ways, shaping the house above like a long-prowed Malay fishing boat. The “bow” of the boat is a cool covered verandah, high above the trees and lush foliage across the property. The peak of the house holds the master bedroom, cradled beneath a high-ceilinged room of handmade ceramic tiles. “Ibrahim, the craftsman, made a detailed map of the windows around the house. Each frame was made individually and the translucent, patterned glass cut to fit exactly in that window alone,” says Dato’ Salinger, remembering the man he worked with for so long on this house. “All of the assistants were over sixty when the job started so the amount of skill they possessed was phenomenal.” Most of the structure has no nails, no screws, no mechanical fasteners at all. “The seats and floor boards are nailed down,” chuckles Dato’ Salinger. “But where you are sitting is a straight drop to the ground”. Pointing to the top of the verandah roof, he mentions a particularly complex joint above our heads. “Only wooden pegs were used at critical places. The remainder of the structure is a gigantic hardwood jigsaw of carefully made cuts and spans held together by the force of gravity.” … Around each doorway are carvings of key passages from the Quran. Carved by two of Malaysia’s foremost wood carvers, the intricate and beautiful letters are raised in ornate and rich wood frames. “Ibrahim helped me build the house,” says Dato’ “and from the proceeds made the Haj to Mecca where he died and is buried.”” (ExpatGo Staff, June 13 2012: |"Handmade History").

“The house is also built with no nails in the main structure, and almost every doorway has a woodcarving crafted by Haji Wan Su Othman and his son Wan Mustafa, Malaysia’s foremost wooden carvers. “None of the people involved in building this house are alive anymore,” he says.” (Dzireena Mahadzir @ The Star, 12 Mar 2006: |"The house that Rudin built").

“We learned that no trees were felled on this property, except where the house actually stands. In addition to fruit and rubber trees, there were sixty assorted native plants on the property, including cinnamon, cloves and breadfruit.” (M. Maxine George @ Magic Carpet Journals: |"Rudinara, A Malaysian Cultural Experience").

1998-10-09: Anugerah Seni Bina Aga Khan

Pada 9 Oktober 1998, Rudinara adalah salah satu penerima anugerah seni bina Aga Khan, di Granada, Sepanyol:-

“Granada, Spain, 9 October 1998 - Addressing culture ministers, diplomats, architects, planners and civic dignitaries in the Generalife gardens in the presence of King Juan Carlos and Queen Sophia of Spain, His Highness the Aga Khan, Imam (spiritual leader) of the Shia Ismaili Muslims, spoke during the ceremony to announce the winners of the Seventh Cycle of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture.” (Aga Khan Development Network, 1998: |"Winners of the seventh Cycle of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture").

“Award Cycle: 1996-1998 Cycle. Status: Award Recipient. … The jury found that the house demonstrates that high technology and energy-depleting services can be renounced if sufficient craft and creativity are deployed, and that the deeper meaning of a vernacular architectural tradition can be combined with the surroundings of contemporary everyday life.” (Aga Khan Development Network, 1998: |"Salinger Residence").

“The house is an architectural feat in more ways than one and was crafted by master craftsman Ibrahim Adam, who was blind in one eye and had no right hand. When he received the letter of the nomination for the award, Dr Rudin drove all the way to Ibrahim’s house to tell him the news: “I drove all the way (to tell him of the nomination) and when I returned, I got the letter saying we had won the award, so I had to drive all the way back!” laughs Dr Rudin, who took the craftsman along to Grenada, Spain, to receive the award.” (Dzireena Mahadzir @ The Star, 12 Mar 2006: |"The house that Rudin built").

Latar Anugerah Seni Bina Aga Khan / Aga Khan Award for Architecture (AKAA): “AKAA, a triennial award, was established in 1977 to “address contemporary issues [of development] and sustain a dialogue with the best Islamic architectural achievements of the past.” The late seventies was a time when the Eurocentric paradigm of development with the West as the singular measure was being interrogated. Under the Eurocentric paradigm of development, the non-West was regarded as backward and underdeveloped with the perpetual need to “catch-up” in order to achieve emancipation from poverty and attain “progress.” Although development was premised upon the promise that “things are getting better all the time,” its prolonged failure to deliver led instead to the perception that the paradigm of development was producing and sustaining the underdevelopment of the “Third World.” Hence, development theories and the underlying Eurocentric modernist discursive formations were seen as a form of neocolonial geopolitics that enabled the continual hegemony of the West through the use of “developmental language of emancipation to create systems of power in a modernized world.” … Issues of development are deeply entwined with questions of modernity and inevitably, one of the recurring themes in AKAA’s discourse is that of “the dichotomy between ‘modernity’ (al-hadatha) and ‘tradition’ (al-turath).” … The extent of AKAA’s reverence for tradition was such that it was accused of having “a romantic bias towards traditionalism, historicism and the vernacular” by a dissenting member of the grand jury. … Hence, it is not surprising that “traditional” and “vernacular” are used in interchangeable manners whereby traditional is equated with that which is indigenous to the region while the vernacular architecture is assumed to be traditional and timeless. … Such a formulation is not dissimilar to the environmentalists’ criticism of the techno-centricity and the domination over nature of modern industrialization, and their harking back to pre-industrial ideas about nature and man’s harmonious relationship with nature through the reiteration of “demised” non-Western traditions. … In contrast to “unnatural” development and modern architecture that alienates man from his “natural” environment, traditional architecture is constructed as “natural” in that it returns man to his pre-industrial ontological essence of “dwelling” in harmony with nature.” (Jiat-Hwee Chang @ Explorations, Volume 7, Number 1, Spring 2007: |"“Natural” traditions: Constructing tropical architecture in transnational Malaysia and Singapore", m.s.4-5).

1992-2004: Pusat Kebudayaan

Selain kediaman, ia turut menjadi pusat aktiviti kebudayaan dan orientasi bagi golongan ekspatriat dan pelancong: “The house functions both as a home for the Salingers and a cultural centre of various aspects of Malay culture. The house plays a very important role in this total experience. Dr. Salinger is extremely proud of it and gives the visitors a detailed account of how this project was built. He is gentleman who has a lot of respect for the craftsmen and was closely involved in the building of his house. The division between public and private allows the Salingers to live very happily in their home while receiving visitors quite easily. .. He has a consultancy firm that provides expatriate orientation services. This started as casual lessons on Malay cooking and herbs and has now become a regular cultural event. Visitors are invited to spend a whole day in his house where they take part in typical Malaysian activities such as batik making, rice grinding, etc.” (Hana Alamuddin @ Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), May 1998: |"1998 Technical Review Summary: Salinger Residence", m.s.8-9).

“Arrayed within the house are collected artifacts from all over the country. They include an enourmous cast brass cooking pot spanning almost a meter across. It was made for Dato’ Rudin by a local craftsman. “Last Raya, I cooked rendang for thirty people on the fire downstairs” Dato’ says, hoisting the massive pot in his arms. In his house, Dato’ conducts cooking classes which focus on local ingredients and cooking methods and using items collected over the years to turn out solid authentic Malay cuisine. Pausing by the door, Dato’ Rudin stops to examine a massive cylinder used to produce noodles for curry laksa. The dough is made of flour and sago flour, being thick and viscous. Suspended over a pot of boiling water, the dough is squeezed out through holes to cook instantly.” (ExpatGo Staff, June 13 2012: |"Handmade History").

Liputan salah satu aktiviti kebudayaan di situ:-

“Under Rudin’s tutelage we learned how to open a coconut, extract its milk with a kapitan and simpal, then to shave the meat of the coconut on a traditional kukur kelapa. Then we were given the opportunity to try the technique ourselves . We made puffed rice and used a stone grinder, known as a kisar, to make rice flour. It was interesting to learn how these and other ancient practical tools, that we were also shown and experimented with, were used.”

Kiri: “Rudinera, the hand built house by master craftsman Ibrahim Adam.”

Tengah: “Dato’ Rudin Salinger explains how to open a coconut.”

Kanan: “Yvonne experiments with traditional cooking methods.”

“Following this we were taken to an outdoor cooking area, with a roof and open sides. Here our host explained how he prepared our lunch. We saw pots of food simmering over an open fire. We were shown how to make a lacy bread, known as roti jala on a traditional, outdoor wood stove. We were all given the opportunity to pour out some of the lacy bread, onto a hot pan, to cook for our lunch. While the meal continued to cook over the outside fires, we were taken back to the patio. Before entering his home, we all took off our shoes and then washed our feet with water ladled out of a crockery urn. We followed our host up the winding stairs to the next level of the house, then out onto the deck, known as the Anjung. Our lunch was to be served out there. After a refreshing fruit drink, numerous serving bowls were laid out onto large, woven bamboo mats. There was a tasty assortment of food. Rudin explained that it is customary to eat the meal without utensils. He explained how we were to curve our fingers towards ourselves, then use our thumbs as pushers to get the food into our mouths. There were bowls for hand washing. We sat cross-legged on the mat and soon were all into the spirit of the meal.”

Tengah: “It is customary to wash your feet before entering the house.”

Kanan: “Lunch at Rudinara.”

“After eating, we were taken outside for a tour of the garden. Rudin demonstrated how to tap a rubber tree and told us about other flora and fona native to this country.”

Kanan: “Rudin demonstrates how to tap a rubber tree”

(Sumber: M. Maxine George @ Magic Carpet Journals: |"Rudinara, A Malaysian Cultural Experience").

2004-2006: Kemerosotan, dan Penjualan

Sejak seawal tahun 2002 lagi, binaan rumah ini telah mula menampakkan tanda-tanda kerosakan. Sekitar tahun 2004, ia tidak lagi dijadikan pusat kebudayaan, dan kawasan kejiranan di sekitarnya turut mengalami perubahan yang drastik. Ia juga dikatakan mula diusahakan untuk dijual: “…when I visited Jimmy Lim in August 2004, I was told that the Salingers had sold their residence and it is no longer serving as a “Malay cultural center.” When I asked Lim for directions to visit the Salinger Residence, he was evasive, claiming that the neighborhood had changed beyond even his recognition and dissuaded me from going there. Instead, Lim drove me around Kuala Lumpur to view other well-maintained houses he designed. I subsequently found out from a former student of mine who visited the Salinger Residence in 2002 that the house has weathered badly and was in a dire condition – the timber structures were decolorized and stained with algae and many of them have hairline cracks (Figure 15).” (Jiat-Hwee Chang @ Explorations, Volume 7, Number 1, Spring 2007: |"“Natural” traditions: Constructing tropical architecture in transnational Malaysia and Singapore", m.s.18).

“Unfortunately, Dr Rudin, who is now 75, and Munira are hoping to sell their dream house as they find it hard to maintain. The thought of Rudinara falling into a stranger’s hands is a painful one, but the couple hopes that the buyer will love the house for being unique and quintessentially Malaysian.” (Dzireena Mahadzir @ The Star, 12 Mar 2006: |"The house that Rudin built").

2019: Pemindahan

Sekitar tahun 2019, rumah ini dipindahkan ke tapak baru di Paroi berhampiran Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, setelah ianya dijual beberapa tahun sebelumnya, dan tapak asalnya diperolehi pemaju untuk pembangunan semula: “While there does not seem to be much discourse on this issue in Malaysia, expansive plaudits and acclamation have been forthcoming from established leaders in the Malaysian heritage arena for some recent projects which saw heritage buildings being relocated to new sites. These include the so-named Rumah Pusaka Chow Kit a.k.a. “Rumah Degil”, was moved (2018) a distance of around two (2) km, and now sits snug between Balai Seni Negara’s main gallery building and its administrative annex block in Kuala Lumpur; and the “Salinger House” originally located in Bangi, Selangor (built 1985-1992), and which is in the last stages of being reconstructed in its new home near Seremban, Negeri Sembilan. This is a result of the house being sold a few years ago to its current owners after the land on which it was originally located was sold separately for redevelopment.”

Salinger House, di tapak barunya di Paroi, Negeri Sembilan (Elizabeth Cardosa, President of Badan Warisan Malaysia, January 16, 2019: |"Let’s Talk Heritage: Relocate and save but risk losing its authenticity? Or keep in-situ and risk losing it altogether?").

Pemilik barunya kini ialah Dato’ Fadhil Dato’ Rashid: “Sebuah buku bertajuk Resurrection of Rudinara Salinger House hasil tulisan Prof. Madya Abd Rahim Awang telah diterbitkan di bawah kerjasama antara Lembaga Perindustrian Kayu Malaysia (MTIB) dan Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) Selangor. Buku ini mengisahkan sejarah pembinaan sebuah rumah kayu yang asalnya dibina di Sg. Merab, Bangi sebelum dipindahkan ke Seremban. … Pemilik baru rumah kayu tersebut, Dato’ Fadhil Dato’ Rashid dan isteri, Datin Rosedina Dato’ Mohd Shamsudin serta arkitek Prof. Madya Dr. Ar. Jimmy Lim turut hadir ke majlis penyerahan buku tersebut.” (Azuwa Yusof @ SWATV MEDIA, January 18, 2022: |"MTIB-UITM SELANGOR TERBIT BUKU RESURRECTION OF RUDINARA SALINGER HOUSE").

Latar Peristiwa

“The 1980s saw a resurgence of tropical architecture in Malaysia and Singapore’s architectural discourses. From key regional academic publications such as Tay Kheng Soon’s Megacity in the Tropics (1989) and Ken Yeang’s Tropical Urban Regionalism (1987) to popular picture books such as Robert Powell’s Tropical Asian House (1996) and Tan Hock Beng’s Tropical Architecture and Interiors (1994), numerous publications propagated tropical architecture and urbanism. This resurgence of tropical architecture came after decades of invisibility, when it hardly featured in architectural discourses. The last time tropical architecture featured prominently in architectural discourse in Malaysia and Singapore was in the 1950s and 1960s, during the period of decolonization and nation-building. Tropical architecture then referred to the International Style modern tropical architecture, as popularized in Maxwell Fry’s and Jane Drew’s seminal book Tropical Architecture in the Humid Zone (1956). Modern tropical architecture was preceded by Colonial tropical architecture, as exemplified by the British Colonial Bungalow in India. There exists the notion that “tropical architecture” was a colonial invention and one may argue that the resurgence of tropical architecture in the 1980s would inevitably be entangled with this colonial and neo-colonial history of tropical architecture but that is not within the scope of this paper. The recent resurgence of tropical architecture brought about diverging tendencies in architectural designs, from ecological tropical architecture to neo-traditional tropical architecture to modern tropical architecture, and became a highly contested domain; one of the perceptible differences with its modern and colonial predecessors is the emergence of a type of architecture that appears traditional. This type of architecture appears to be traditional because it bears certain formal resemblances to traditional vernacular architecture and it is often constructed out of similar local construction material such as tropical hardwood employing traditional building crafts. However, this type of architecture that resembles traditional architecture needs to be differentiated from the traditional architecture in that they are produced in contemporary conditions under current social, cultural, political and economic contexts. Moreover, the contemporary architect chooses to produce this type of architecture as a conscious decision, selecting from a wide array of aesthetic choices presented to him. This emergence of an architecture that appears traditional is especially apparent if we look at the award winners of Aga Khan Award for Architecture (AKAA) in Malaysia. Three of the four AKAA winners in Malaysia – Tanjong Jara Hotel and Rantau Abang Visitors’ Center, Salinger Residence, and Datai Resort – fall under this category of tropical architecture. Interestingly, although these three AKAA winners appear traditional, their referents are not explicitly any type of particular traditional architecture per se, despite apparently bearing certain formal resemblance to particular traditional architecture. Instead, they are considered primarily as tropical architecture, with the referent being directed towards the primacy of tropical “nature” with the associated abstract notions such as environment, climate and ecology. … I will argue that both “nature” and “tradition” are valorized in the resurgence of tropical architecture and deployed for an array of purposes within the abovementioned themes– to validate and revive subjugated traditional architecture in the quest for alternative paradigms of development; to deflect the questions of problematic traditions in a multicultural, multiracial nation; to unify diverse traditions in a vaguely defined region; and to differentiate and thematize places in order to encourage new modes of consumption. However, despite all these different strategies of deploying “nature” and “tradition” by different agents, they are, inevitably, also very much structured by the hegemonic logic of capital accumulation. Instead of understanding “nature” and “tradition” as timeless and immutable entities, I argue that “nature” and “tradition” are continuously constructed and re-constructed, valued and de-valued according to the various strategies outlined above, and complicit with the capitalist modes of production and reproduction.” (Jiat-Hwee Chang @ Explorations, Volume 7, Number 1, Spring 2007: |"“Natural” traditions: Constructing tropical architecture in transnational Malaysia and Singapore", m.s.1-2).